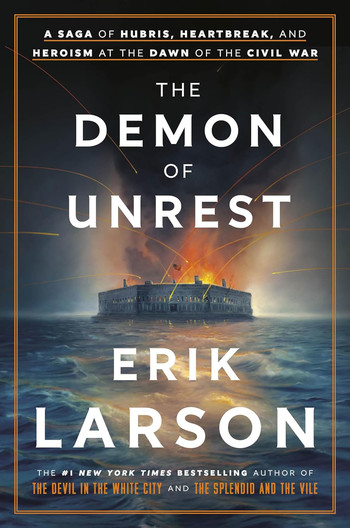

Exactly how did the American Civil War begin? This was the question Erik Larson was pondering when he began working on a new book in the first weeks of the COVID pandemic. After writing three histories of wartime Europe, most recently The Splendid and the Vile, which detailed the first year Winston Churchill ’46HON served as Britain’s prime minister, Larson set out to research a subject closer to home. Of course, everybody knows how this bloody chapter in American history ends, but Larson’s account of the political crisis that led to the first shots being fired in Charleston Harbor reads like a thriller and positively drips with tension.

The Demon of Unrest gives us a front-row seat to the five months of drama that unfolded between Lincoln’s election and the attack on Fort Sumter. Larson is known for his exhaustive research, and here he draws on hundreds of historical documents, including letters, telegrams, military reports, personal diaries, and plantation ledgers. From these he painstakingly reconstructs the unfortunate series of events that led “Americans on both sides of the Mason-Dixon Line to the point where they could actually imagine the wholesale killing of one another.”

What his research reveals is sobering. Yes, the issues of slavery and states’ rights were certainly the chief sources of political tension, but the march toward war was propelled not just by principles but also by a string of misunderstandings, hurt feelings, misplaced codes of honor, and naked narcissism. Indeed, the “unsatisfiable craving on the part of certain key actors for personal attention and affirmation” was a key driver of civil unrest.

We learn about the role of Edmund Ruffin, a puffed-up Virginia planter who was afforded the dubious honor of firing the first shot in the attack on Fort Sumter. Ruffin, a vocal instigator of secession, was vain but terribly insecure. He desperately chased the spotlight, embraced his role as a rabble-rouser, and sought praise and flattery constantly.

Pride was also a distinguishing characteristic of the three envoys of the Confederate States who, in the days leading up to the war, traveled to Washington in the hopes of meeting with President Lincoln. “Proficient in the art of taking offense, they needed the unalloyed respect of all around them,” writes Larson. When the trio were summarily rebuffed, they angrily threatened “blood and mourning” and said they would “accept the gage of battle thus thrown down to them.”

While male ego played an outsized role in this tragedy, heroism also drove the action. Fort Sumter was manned by the courageous Major Robert Anderson, who despite dwindling supplies and insufficient arms, bravely defended his position even as the fort was surrounded by the enemy. Cleaving to the most revered principles of military etiquette (yes, another sort of pride), he kept the American flag flying under the greatest duress.

In the book’s introduction, Larson says that during his research, he couldn’t help but have “the eerie feeling that present and past had merged.” Then as now, the nation was deeply divided, with one member of the cabinet declaring, “The people in the South are mad; the people in the North are asleep.” In February 1861, the certification of the Electoral College vote was under threat, as crowds of irate Southerners gathered in Washington and converged on the Capitol, clamoring to get inside. Polarization was fueled by men with deep passions, massive insecurities, huge egos, and conflicting economic interests. Thus, with flag-waving, cheers, and an overdeveloped sense of indignation, the nation blundered into a civil war that would result in the loss of some 750,000 American lives. This terrifying conclusion, one might argue, makes Larson’s latest tome not just a saga of hubris, heartbreak, and heroism, as the subtitle suggests, but a sobering and timely cautionary tale.