No professor has taught at the UC Berkeley Graduate School of Journalism for as long as William Drummond '66JRN, '66SIPA, now in his 36th year as a faculty member. Before starting his academic career, Drummond covered civil rights for the Louisville Courier Journal, reported from New Delhi and Jerusalem for the Los Angeles Times, and was the founding editor of Morning Edition at NPR.

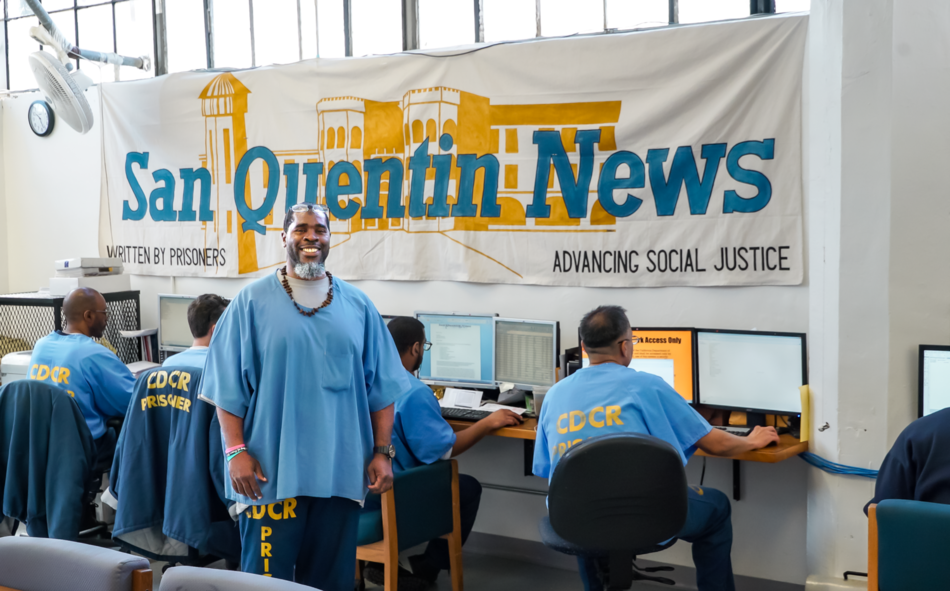

Between reporting stints in the 1970s, Drummond worked in the Carter and Ford administrations as a White House Fellow. The program promotes active citizenship and public service, and Drummond has long taken that message to heart. For the past eight years he and his Berkeley students have volunteered to help inmates produce a newspaper inside California’s oldest prison, San Quentin. He writes about that experience and his life growing up in West Oakland, California in a new book, Prison Truth: The Story of the San Quentin News.

How did you start volunteering at San Quentin?

By accident, in 2012. One of my best students in the '90s, Nigel Hatton, a young Black man from Oakland who was on the faculty at UC Merced, started volunteering at San Quentin for the Prison University Project. And because of Nigel, I was invited to San Quentin to teach the inmates an introductory journalism class. At that point, I had lost faith in journalism to a certain extent, because I felt like the transition to digital media had de-emphasized the importance of good editing. San Quentin was where my redemption started. It was stimulating for me to see how eager the inmates were to learn, and to listen to them tell stories about their experiences. That’s when I knew I had hit upon something. Today, the San Quentin News is the only regularly published newspaper in the California prison system. It goes to all the other prisons in the system and to state legislators and other government officials in Sacramento, with a total circulation of 30,000.

What are some of the major challenges of teaching journalism to inmates?

Outside the prison, the First Amendment protects your right to publish. But if you violate what’s allowed at San Quentin, the paper can be and has been shut down. You’ve got to figure out a way to reconcile the realities of working in a prison environment with the tenets of journalism. Every journalism organization I have ever worked for has areas that are off-limits. At San Quentin, it’s the same. The inmates know they can’t use the newspaper to grind their personal ax, and they can’t write inflammatory stuff.

In the book you say you’ve learned more from the editing staff of the San Quentin News than they’ve ever learned from you. Can you elaborate?

My greatest teacher was the late Arnulfo Garcia, a former editor in chief of the San Quentin News. He demonstrated how to waltz with power. He had the keenest sense of politics of anybody I’ve ever met. Considering that he was a prisoner, he managed to win over the warden and the public-information officers, who eventually let him do unprecedented things. His achievements went beyond what was published in the paper. For example, he was able to launch the forums that brought judges, legislators, district attorneys, and cops for sit-downs with inmates. He understood the “art of the possible.” More importantly, as a manager, he was a great leader. He got a cantankerous and ornery group of galoots to work together, and won the trust of the civilian advisers. Not bad for a tenth-grade dropout. Until I met Arnulfo, I was pessimistic about changing people’s minds. I would walk away. Arnulfo would stick around and engage with people. Little by little, he’d get his way. I got the education, not him.

You have some personal experience with violent crime — when you were twelve your mother was shot and killed by a jealous boyfriend. You heard the gunshots from your bedroom. How do you think your work with prisons has helped you process that awful memory?

When I began writing the book, I started reflecting back on the murder, including the time when the district attorney, preparing for the trial, actually showed me pictures of my dead mother from the morgue. At that point I just wanted to go back to having a normal life. Years later, when I was at the Los Angeles Times and was assigned a story on San Quentin, my curiosity about what happened to the perpetrator overwhelmed me. After spending time with a prison counselor, I felt I could trust him to look up the information. He went to the prison records section, came back, and was very curt. He just said, “no, he’s not here.” He didn’t have any other information. It kind of piqued my interest because it didn’t seem like he was being 100 percent honest with me. Still, I achieved some kind of closure. It was the first time that I tried to follow up about the man who killed my mother. I rarely, if ever, had mentioned the murder to a friend or anyone close to me. It was just too hard to explain.

You’ve probably spent more time behind bars than most journalists, both as a reporter and now as a volunteer. How has volunteering changed your perspective?

I don’t accept the idea that a person is born a criminal. I don’t understand what that means. There is no such thing as a criminal “type.”

Are you saying that everyone who commits a heinous crime can be rehabilitated?

Every study will prove that point. Sure, there are some exceptions — serial killers. But they are a tiny, tiny fraction. When I go over to San Quentin, I don’t ask the inmates at the newspaper about their crimes. We’re trying to achieve a goal — putting out the paper and getting them rehabilitated so they can go home. But I confess, out of curiosity, I sometimes look up these guys’ records because I find it hard to believe that some of them are in jail.

Why is it valuable for your students to be comfortable working with inmates?

It’s something I’ve preached since I started teaching thirty-odd years ago. As a journalist, you have to be comfortable enough to talk with the bank president and with people on the street. You “code switch” — talk to people on their level without being condescending. When I take students to San Quentin for the first time, they’re usually scared and bewildered. But then they meet the inmates within the security of the newsroom, and they talk and talk. They walk away feeling empowered, realizing that they can go into the real world and not be intimidated. For the inmates, there’s also a big bonus working at the San Quentin News. They may only earn a dollar a day, but they get to talk with people who aren’t corrections officers or prisoners. The prisoners have the experience of suddenly being seen as human again.

How did you learn the art of talking with people from all walks of life?

On a whim, when I was at the Columbia Graduate School of Journalism in the mid-1960s, I decided to take a class with Samuel Lubell '33JRN, a well-known pollster and one of the few people to predict that Truman would beat Dewey in 1948. He had students go onto the streets with surveys, and he would feed the results into his data. My job was to go to East Harlem, which was Puerto Rican, and strike up conversations with people. This was how I overcame my natural fear of walking up to strangers. It served me well for the rest of my career.