“Jimmy, there is too much to think about you, and too much to feel,” began the writer Toni Morrison in her eulogy for her friend James Baldwin in 1987. Her reflections on Baldwin’s life also capture something essential about his work as an essayist, novelist, poet, and activist. “Your life,” she continued, “refuses summation — it always did — and invites contemplation instead.”

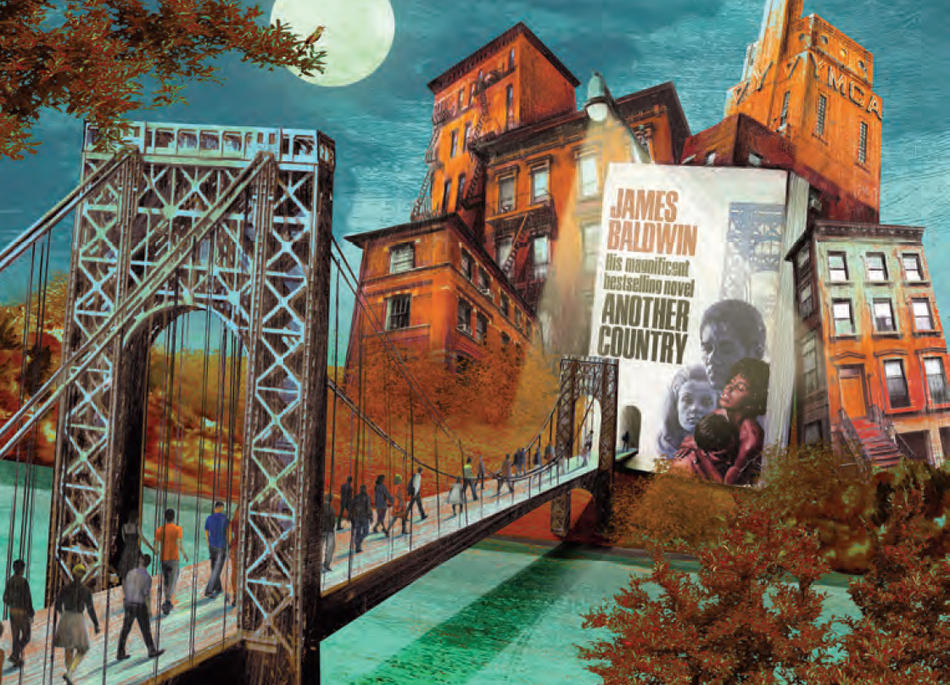

Now, a yearlong citywide celebration of James Baldwin (running through June 2015), organized mainly by Harlem Stage, Columbia’s School of the Arts, and the dance organization New York Live Arts, commemorates — and contemplates — the man and his work in what would have been his ninetieth year. In May, the School of the Arts held an intimate discussion of Another Country, Baldwin’s best-selling 1962 novel.

The choice of this book, which explores the complexities of race and sexuality, is not surprising, though the choice of speakers — author and professor Colm Toíbín and actor Jake Gyllenhaal ’02CC — might be. A long line of people assembles outside the Frank Altschul Auditorium, among whom it is tough to decipher who came for a love of Baldwin, who for a respect for Toíbín, and who for the rare opportunity to see Gyllenhaal up close. A young student turns to her friend and asks the question on so many minds: What’s Jake going to do? Surely, Toíbín could speak to his and Baldwin’s shared literary concerns: their wrestling with nationhood (Toíbín is Irish) and sexual identity. But how exactly does the handsome actor, who studied religion at Columbia, fit in the picture?

Inside the auditorium, Toíbín and Gyllenhaal walk to center stage and sit in wooden chairs. Toíbín, the unassuming academic in his black jacket and blue jeans, and Gyllenhaal, the heartthrob with his hair slicked back in a ponytail, look like a professor and student sitting down to coffee during office hours. After a roar of applause, Jake reveals that his sister, the actress Maggie Gyllenhaal ’99CC, gave him a copy of Another Country while he was a student. “The place where I was, the streets of New York,” he says, “and grappling with this intellectual hierarchy ... I just found this book to be everything when I read it.” Toíbín, too, is compelled to justify his presence at this discussion, remembering the thrill of first learning that Baldwin was gay. “Oh my God! I thought I was the only guy who was like this, no one else.”

At that moment, anyone wondering why a talk on Baldwin was being led by two white men — and not, for instance, by Rich Blint, Columbia’s associate director of community outreach and education, and the event’s organizer, who is black, gay, and a Baldwin scholar — would have found the answer: Toíbín and Gyllenhaal are two members of the diverse group who make up what Baldwin referred to as his “tribe.” This tribe, composed of the artists who have been touched by his works, reinforces Baldwin’s legacy not just as a writer but also as a humanist. As Farah Jasmine Griffin, a Columbia professor of English and African- American studies, points out in her introduction for the evening, Baldwin’s writing helps us trudge through “the muck and the mire of our historically inherited and constructed identity to meet each other face to face as human beings.” Novels like Go Tell It on the Mountain (1953) and book-length essays like The Fire Next Time (1963) accomplish this through their examination of identity politics and spirituality.

Another Country begins with Rufus Scott, a young black musician searching for purpose and fulfillment. “It’s almost as if Rufus is a kind of Hamlet,” says Toíbín. “In other words, he can transform himself. He can put an antic disposition on. He can be bad. He can be funny.” This was key for Baldwin, who was determined to create black characters with full agency — something he felt his friend (and future ex-friend) Richard Wright was never able to accomplish. Hence, Rufus’s downfall is as much a result of self-destruction as outside social forces. That is precisely what makes him so real. The rest of the novel follows Rufus’s sister Ida, his best friend Vivaldo, and their friends Richard, Cass, and Eric. “They’re moving towards, and trying to have, love, whatever that is,” Gyllenhaal observes, and Baldwin exposes “the cruelty of that and the beauty of that.” We know these people. They are our friends and lovers.

It took Baldwin almost twelve years to complete the novel — an exhaustive process in which he experienced some of his lowest lows while wandering from New York to Paris to Istanbul. Labeled brilliant and obscene, Another Country, with its interracial love affairs and same-sex relationships, addresses many taboos that still exist today. Its mixed reception seems fitting for a man of so many contradictions. James Arthur Baldwin loved his home of Harlem, flourished in Greenwich Village, and spent many years in Paris. He had countless famous friends but was often lonely. He made massive contributions to our culture, yet he is frequently left out of the curriculum in American schools.

Among his tribe in the auditorium, though, Baldwin is very much alive. He is there when Gyllenhaal recites his words and when Griffin declares him “preeminent.” On this night, Baldwin, like his tormented hero Rufus, “is the center of the universe,” as Toíbín explains, “and then he’s gone” — leaving us with the task of remembering, and now, reviving.