Darling, I know it’s been a long time, but the wait is over. Enclosed please find Laura Cantrell’s fifth studio album, No Way There From Here. Once you find it, open it and put it on.

This is not some ploy to win you back. We’re way past that. But I know you’ve been waiting, as I have, for more Laura, like waiting for the roses to bloom again, and also the acoustic and twelve-string guitars, banjos and fiddles, the bright peal of a chatty piano, and a voice as close and familiar as the tree in your front yard. Cantrell’s voice has never sounded clearer, prettier, or wiser than it does in these twelve tracks — modest, decorous, intelligent, buoyantly melodic, and Southern: plain in the best sense of the word.

Did you know she recorded the album in Nashville? And that she wrote or co-wrote all but one of the songs? That’s why I’d call it her most personal album. After all, she grew up in Nashville, which struck me at first as a marvelous coincidence, though I suppose my logic was inverted. Anyway, Cantrell lives in New York and is very much at home on this record. The musicians she’s assembled are among Music City’s finest: with clarity and reserve, they offer empathic support for Cantrell and her frequent collaborator, guitarist Mark Spencer.

But the main event here is the songwriting. Cantrell ’89CC has long been a student of songcraft and an interpreter of others’ material, a regular country-music almanac who, in her college days as a DJ on WKCR, revived and hosted the Tennessee Border radio show. How glorious, now, to get a full basket of her own expertly crafted three-minute pop inventions, twilled with a radio-and-blue-jeans innocence that we didn’t know was innocence until we lost it to MTV, the Internet, and a dozen bad decisions. Cantrell is a poet of squandered Edens, of pasts out of reach. The title track states the truth we’d rather forget: “No bridge across the ocean / no path up through the mountains / or trip back through the years” — no way there from here.

Cantrell’s is a distinctly pre-digital world. People don’t e-mail or text. They write postcards and send letters and wait for letters that never come. They sing along to the kitchen radio, they yearn, they dream, they suffer, they survive, cared for by their ever tactful creator. In “Letter She Sent,” a gal named Mary “came home with smoke in her hair / and her stockings on crooked / but she didn’t care.” That’s as risqué as it gets, by the way, unless you count the girlish, longing storyteller in “Driving Down Your Street,” whose fantasy progresses from the street to the front door to the landing to being “barefoot ’cross your floor” — and now it occurs to me, by the military ruffles of the snare drum, and the line “there’s a chain around your neck / and my heart’s caught up on that chain,” that the “you” she’s singing to might be off to war — or lost to it. Point is, lovers in Cantrell’s songs barely make it to first base: they hold hands, they kick off their shoes and lie down in the green, green grass. (Remember those days, dear?) Cantrell respects not just our intelligence but also our imaginations.

Another epistolary gal, Donna, went to the store and “spent all she had and a few pennies more.” Dollars would sound vulgar. It’s pennies. And women listen to bands in smoky bars, wear nylons, and are named Mary, and when their letters go unanswered, they drink. Or shop. Maybe they’re “just working out who they are,” as Cantrell sings in the album’s jangling opener, “All the Girls Are Complicated.” It’s a world, too, of garden gates, highways, coloring-book weather: gray skies, starry skies, twilight skies, January days that feel like June. Oranges in the winter that “taste like sunshine.” Cantrell doesn’t risk sentimentality so much as redeem its noble essences. Irony doesn’t even bother getting out of bed, though its eyes are open. Cantrell’s control extends to her cleverness. She doesn’t spoil a good thing.

Still, her effects can be deceptive: few singers summon as much emotion without emoting. She plays it straight, relying on the unfiltered quality of her voice, rather than any histrionics or technical virtuosity, to do the job. She’ll marry melancholic lyrics to good-time strumming, or enunciate simple pleasures over a lonesome, pedal-steel sigh. She’ll lull you into rivers that run a little deeper than you’d thought, then snare you in a net of melodic beauty. Her engagement with the past, musically and thematically, produces an undeniable nostalgia, but with Cantrell it feels like the vital present, which gives her songs the thrift-shop virtue of sounding as good now as they would have forty years ago — or will forty years hence. I’m not talking about timelessness; it’s more like the stopping of time, the crystallization of a moment, a memory, that we can enter and leave.

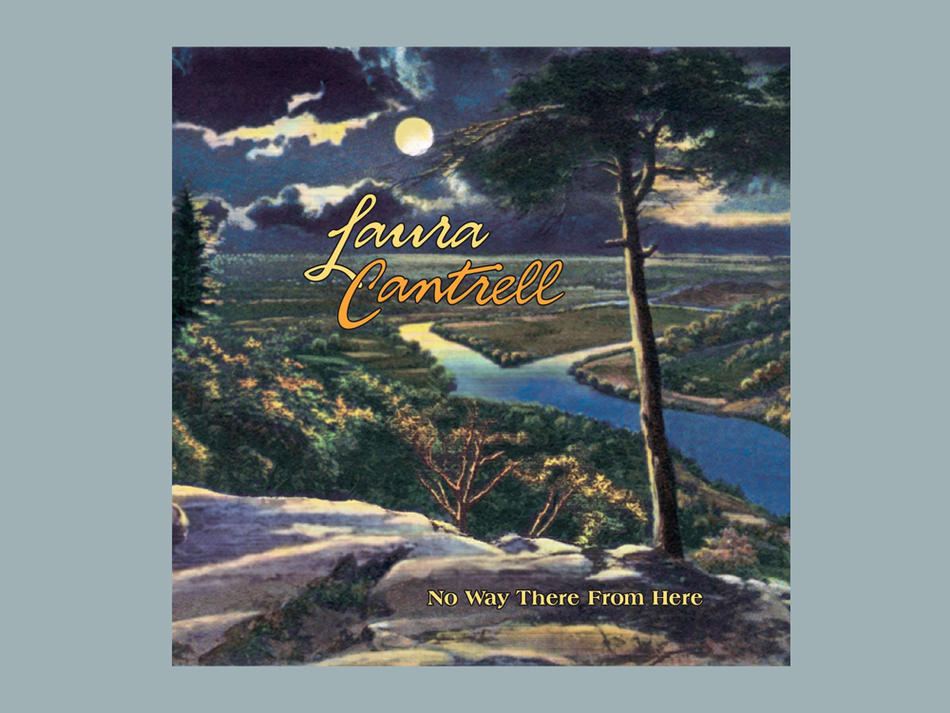

All the songs on No Way There From Here offer the customary Cantrell delights. There’s the gorgeous one-off chorus of “Barely Said a Thing,” which evokes the body of the Cherokee River, otherwise called the Tennessee River (the same river, perhaps, that’s depicted pastorally on the album cover — a vision of paradise floodlit by something like the “big yellow moon in my window pane” that reassures the solitary chronicler of “Starry Skies”); the humming, bittersweet meditation on letting go in “Someday Sparrow”; the desolate soliloquy-to-an-ex in “Washday Blues, ” with its post-breakup account of bruised coping, punctuated by the singer’s insinuating, intimate refrain of “you know what I mean?”

You might find it interesting, as I did, that Cantrell’s toughest, most defiant statement of after-the-split, I’ve-changed, won’t-look-back resilience turns out to be the record’s one cover, “Beg or Borrow Days,” written by the Brooklyn musician Jennifer O’Connor. Cantrell, as ever, makes another’s composition entirely her own — in this case, a festive hoedown — then follows it with “When It Comes to You,” a stark, shuffling confession of helpless love that includes the line “I’m a beggar and I fail every test.” The juxtaposition of the two songs is jarring, and utterly true: one’s armor can so easily slip.

But if there’s one tune that nearly breaks me, the one that puts a finger to the old welt and a thumb to the faded photos in the back of the closet, it’s “Can’t Wait,” an airy, toe-tapping, tightly strung embroidery of sweetest anticipation, in which the narrator sings of “pourin’ out my heart to these four walls” as she waits for the return of her hard-working love. When you come home, darlin’, I will fill your plate. I can’t wait, I can’t wait, I can’t wait. You can decide for yourself if, at the end, the wait is rewarded. But given the silver thread winding through the album (and through much of Cantrell’s work) of swollen-hearted lovers waiting for things that never come, there is room to wonder.

I hope you get this letter, darling. I look forward to your reply.