Political scientists often classify themselves as either empiricists or interpretative analysts. The career of Charles V. Hamilton reflects both traditions. His search for meaning within politics is found in his teaching, writing, and speeches. He was a teenager when the publication of Gunner Myrdal’s An American Dilemma: The Negro Problem in Modern Democracy (1944) spotlighted the country’s racial issues and when President Truman integrated the military (1948), in which Hamilton served for a year. A chronicler of the Civil Rights Movement, he was a young adult at the time of Brown v. Board of Education (1954) and the Montgomery Bus Boycott (1955–56). He lived through the Jim Crow era and witnessed the political transformation that made possible the election of black officials in the South. Watching the unfolding of civil rights history informed and enriched his scholarship as he created a role for himself as an intellectual amongst activists.

Stirring Up Tuskegee

I first met Charles Vernon Hamilton when I was a student at Tuskegee Institute (now Tuskegee University) in Alabama. It was immediately obvious that Hamilton was different from the other professors. Not a Southerner, he did not sound like the rest of the Tuskegee faculty. Students in the dormitories would imitate his charismatic cadences, precise grammar, and impressive diction. He did not behave like most of the faculty, either.

Born in Muskogee, Oklahoma, in 1929, Hamilton had attended Roosevelt University, considered a hotbed of Chicago radicalism when he graduated in 1951. In contrast, in the 1950s Tuskegee Institute was still governed by the conservative ideas of the late Booker T. Washington, who had founded the college in 1881, and his approach to politics permeated the campus culture. Washington stressed economic preparation, rather than protest, as the means of promoting the social mobility of black people. But unlike most Tuskegee professors, who always seemed so deferential toward the school’s traditions, Hamilton was not afraid to discuss the Civil Rights Movement or other controversial issues in class.

Fresh from participating in the Montgomery Bus Boycott, I had no idea what I wanted to do with my life. I was hoping that my courses at Tuskegee would teach me how to facilitate the making of a racially integrated America. However, in 1958, the year Hamilton arrived, most students still rarely left the self-contained campus of this black college where they were protected from the highly segregated, potentially life-threatening surrounding community.

As civil disobedience grew in the South, it was not uncommon for worried parents to write to students warning them to stay away from protests and “just get your education.” Thus, when Hamilton joined the faculty, students at Tuskegee had had little involvement in the types of civil rights actions that had begun to flourish in other places. Some time later, when Tuskegee Institute students held their first civil rights demonstration, against segregation in downtown Tuskegee, it was not surprising that people pointed to Hamilton’s influence.

Always challenging his students to raise their own questions about commonly accepted ideas, Hamilton encouraged us to debate the issues of the day. But whenever anyone made a comment off the top of his head, Hamilton would shoot back, “Show me your data.” Unsupported statements were not acceptable for political scientists, he would tell us.Hamilton quickly gained a reputation for teaching American government courses with a sense of urgency and skepticism. His lectures often contradicted the glowing textbook references to American democracy and the nation’s venerated political institutions. He would point out, for instance, that while espousing the ideals of freedom and democracy, most of the country’s founders were slave owners. He would note that the Supreme Court had ruled on Brown v. Board of Education four years earlier, yet Southern schools were still not desegregated. He would remind students of the signs all around them that read, “White Only” and “Colored Only,” signs that would not come down until 1964. When Martin Luther King Jr. visited Tuskegee in the late 1950s, school administrators, fearful of reprisals from the white community, would not permit him to appear on campus, so he spoke at a local church instead. Sitting in the audience, I realized that Hamilton was the only Tuskegee professor in attendance. At a time when many people (both black and white) saw King as an outsider whose methods of nonviolent protest would only stir up more trouble for black people, Hamilton stood on stage with King and even had his photograph taken with him.

One hot topic was the efficacy of Martin Luther King’s nonviolent confrontational approach versus the legalistic tactics of Roy Wilkins and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. Hamilton had received his law degree from Loyola University in 1954, but he had always wanted to be a college professor and play an active role in the Southern Civil Rights Movement. Thus, he was drawn to Tuskegee since his wife, Dona Cooper Hamilton ’82SW, was the daughter of a professor of veterinary medicine there. Hamilton’s legal training allowed him to appreciate Roy Wilkins’ view that to bring about real change, you had to have the law on your side. Hamilton realized, though, that this was a slow process, and he believed that King’s protests were a necessary element as well.

With the Civil Rights Movement a perfect backdrop for his lectures, Hamilton helped us understand the importance of both approaches in overcoming Jim Crow. However, as he became a model for young people aching to be on the front lines of the struggle, his colleagues and school administrators grew increasingly uncomfortable.

In 1960, when Tuskegee refused to renew his contract, Hamilton walked into a lecture with the termination letter in his shirt pocket. Students saw this as an act of defiance. Although he later told me that he had not been as confident as he acted, his unapologetic expression of his ideas, both inside and outside the classroom, left a lasting impression on me and his other students.

Hamilton’s brief years at Tuskegee had given him the opportunity to gain a better understanding of the civil rights challenges faced by black Americans in the rural South. He went on to receive his PhD in political science at the University of Chicago and to teach at Rutgers University at New Brunswick, New Jersey (1963–64), Lincoln University in Pennsylvania (1964–67), and Roosevelt University in Chicago (1967–69). His students had the privilege of listening to him as he outlined his preliminary thinking about the future of American democracy, ideas that would find their way onto many a printed page.

After Black Power: The Columbia Years

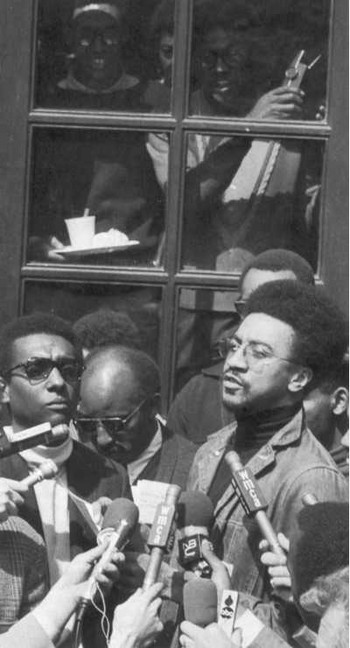

In 1969, Hamilton arrived at Columbia University as a Ford Foundation–funded professor in urban political science and became one of the first African Americans to hold an academic chair at an Ivy League university. It was the height of the turbulent 1960s, and the nation was reeling from assassinations, demonstrations, and riots. These currents were felt with particular force at Columbia.

Hamilton was at the peak of his fame as the intellectual half of the “Black Power Duo.” The activist half was Stokely Carmichael (later known as Kwame Ture), a former leader of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, self-professed Black Nationalist, and nascent Pan-Africanist. In a brilliant stroke, Hamilton had teamed up with Carmichael, a folk hero and icon for his generation, to write what would be Hamilton’s most famous book, Black Power: The Politics of Liberation in America (1967).

Black Power became the manifesto of the black solidarity movement. The popularity of this book had transformed Hamilton into a highly visible public intellectual. Across the country, white Americans wanted to know what black people thought, what they wanted, and how they planned to get it. The book signaled a shift in thinking among black intellectuals: They knew that the triumphal days of the Civil Rights Movement were coming to an end and that they needed to consider the next step. With its theme of self-determination, Black Power allowed the intellectual community to focus more clearly on the future of black people in America. The book became a bestseller and was translated into several languages.

During the 1970s, as New York City experienced a fiscal crisis and underwent a demographic transformation that saw increases in its minority population, City politicians looked to Hamilton for advice. In the 1977 New York mayoral election, candidates competed for his endorsement even though he lived in New Rochelle.

Named the Wallace S. Sayre Professor of Government at Columbia in 1971, Hamilton taught American government, urban politics, and minority politics. A very popular teacher, he drew large numbers of students to his courses. In 1973 Hamilton recruited me as a junior faculty member. During the seven years I spent at Columbia, I taught undergraduate courses in political science and Contemporary Civilization. More important, I had a second opportunity to learn from Hamilton, whom I had not seen since our Tuskegee days 13 years earlier.

Not only did I come to call him “Chuck,” but I also got a chance to watch him teach both undergraduate and graduate students. He once told me that when he first started at Columbia, every course he taught had the word black in the title. However, since his expertise was far broader than protest politics, he soon began to teach graduate courses on public policy and undergraduate courses on American government. Despite his busy schedule, Hamilton was always approachable. The hallway outside his office at the southwest end of the SIPA building was often filled with students discussing City administration, presidential politics, and changes in the black leadership class.

He and I had many lively political discussions as well. I remember his explaining his theory of the connection between welfare and “functional anonymity”—that one unintended consequence of the welfare system was that it made black people less willing to confront social and political inequities for fear that speaking up would cost them their invisibility, and thus put an end to their benefits.

Columbia University’s political science department was divided into four sections: theory, comparative politics, international relations, and American politics. For years Hamilton led the American section, consisting of a fascinating team of scholars that included Demetrios (Jim) Caraley ’54CC ’62GSAS, Alan Westin, Robert Shapiro, and Ira Katznelson ’66CC. When Hamilton and Caraley were interested in starting a master’s program in public administration, they enlisted me to draft the initial proposal for the program. It was adopted and established in the School of International Affairs (now the School of International and Public Affairs).

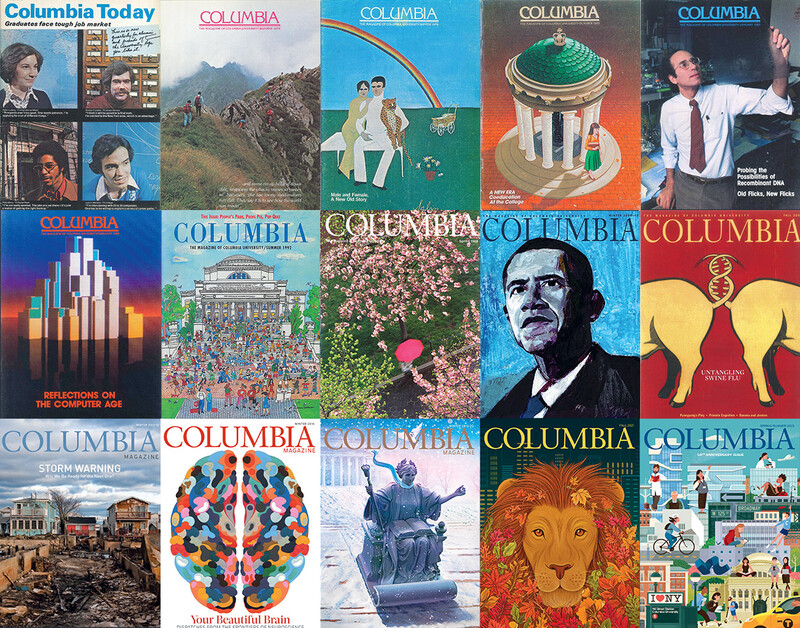

During my time at Columbia, Hamilton assumed leadership of the Metropolitan Applied Research Center (MARC) from the retiring director, Kenneth Clark ’40GSAS ’70HON. Hamilton also served three years (1983–86) as a consultant to the Ford Foundation. Among the many honors and awards he has received, Columbia University presented him with the Mark Van Doren Award for Excellence in undergraduate teaching in 1982 and the Great Teacher Award from the Society of Columbia Graduates in 1986. In 1993 he was elected a fellow in the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. When the Chicago Sun-Times listed the leading scholars in America in 1995, Hamilton was one of four Columbia professors included.

Controversial Encounters

One of Hamilton’s best-received books, Adam Clayton Powell Jr.: The Political Biography of an American Dilemma (1991), demonstrated his skills as a political analyst and historian. The first African American to represent New York in the U.S. Congress (in 1945), Powell was known for his flamboyant antics, which were legendary in Harlem and in the halls of Congress. Hamilton went behind the legend to discover a man with incredible rhetorical talent and legislative skills, yet one who squandered opportunities to accomplish more.

For instance, Hamilton noted that as chairman of the Education and Labor Committee, Powell would attach the so-called “Powell Amendment” to any bill that came before him. Stating that unless states desegregated they would be denied federal funds, this amendment was a symbolic gesture that demonstrated his power to affect public policy.

Like Powell, Hamilton has never been a man to shy away from controversy. He speaks his mind to the powerful and the powerless. He spoke his mind at Tuskegee Institute and at every other institution where he taught. In 1970 Hamilton was among a group of scholars invited to the White House. Apparently President Richard Nixon had read Hamilton’s work and wanted to hear more about solutions to the race problem. In what was supposed to be an off-the-record discussion, as Hamilton later recalled, he urged Nixon “to back off the Black Panthers, to stop shooting them.”

A few months later, in a speech in St. Louis, Nixon said that he had met with Charles Hamilton, from “the University of Columbia,” and that Hamilton had assured him that black people in the United States were better off than those anywhere else in the world, American racial problems notwithstanding. “Those words had never crossed my lips,” Hamilton said. He got his chance to respond to Nixon when a group of scholars published a set of essays in a book entitled What Nixon Is Doing to Us (Harper & Row, 1973).

Another example of his outspokenness came in a speech at a 1976 Democratic National Committee meeting, in which Hamilton suggested that it would be acceptable for presidential candidates to soft-pedal the race issue as long as they dealt firmly and unequivocally with issues that affected the black community once they were elected. No matter how sympathetic candidates were to black causes, Hamilton argued, they could do nothing to help African Americans if they alienated their mostly conservative electoral base and never took office. This statement, reflecting Hamilton’s pragmatism about electoral politics, was not well received by some black activists. However, Hamilton saw his role as explaining the difference between electoral and protest politics.

This speech also provided a preview of his thinking regarding the possibility of “deracialized politics.” Just as he had done in Black Power, Hamilton anticipated the shift in white attitudes toward race, this time concerning the increasing significance of black elected officials. He advised black politicians to deracialize their campaign rhetoric if they wanted to compete in predominately white cities. He reasoned that since there were a limited number of predominately black cities and congressional districts, a change in tactics was indicated if black politicians wanted to be competitive in mixed districts and statewide elections.

At the time, recommending downplaying the race issue in any way and for any purpose was considered heretical. The deracialization thesis was debated vigorously at the 1976 and 1977 annual meetings of the National Conference of Black Political Scientists. However, the idea was vintage Hamiltonian thinking, typically pragmatic. His essay on the topic appeared in The First World, a small journal, under the title “Deracialization: Examination of a Political Strategy.” This essay caused quite a controversy among black political scientists and was one of the central issues in an anthology entitled Race, Politics, and Governance in the United States (1996).

Perhaps Hamilton’s most controversial decision was to attend a conference with aides of the Republican President-elect Ronald Reagan. Hamilton, Percy Sutton, former borough president of Manhattan, and Harvard political science professor Martin Kilson were invited as the only black Democrats at the 1980 meeting sponsored by the Institute for Contemporary Studies. This meeting caused a stir in the black intellectual community as some colleagues considered meeting with Republicans an act of party disloyalty. Hamilton saw it as an opportunity to engage in dialogue with emerging black conservatives who would eventually play a more visible role in American politics.

Hamilton was one of the first black social scientists to visit South Africa during the apartheid era, in 1979. His travels to the garrison state left an indelible impression on him. He became a member of the Council on Foreign Relations and continued to pursue his interest in the political and economic development of the African continent.

In 1997 Charles V. Hamilton retired from Columbia, and, still actively writing, he now divides his time between South Africa and New York. Through his teaching, books, and speeches, Hamilton has provided a platform from which to debate the great issues of the post–civil rights era. Whether broadening the discussion or challenging his colleagues regarding the direction of the struggle for equality, Hamilton has generated some of the most thoughtful scholarship on race in the twentieth century.