If you’ve followed health news lately, you may have noticed scientists shifting their stance on alcohol. While red wine was once touted as life-extending, and moderate drinking was thought to reduce the risk of stroke and heart disease, researchers now warn that alcohol poses a real threat not only to your heart, but to your brain, liver, and almost every other organ in the body.

Meanwhile, Americans are drinking more heavily than they have in decades; the average adult now consumes over 500 drinks a year, and some 180,000 lives are lost annually to alcohol-related diseases and injuries. These trends were exacerbated by the stress of the Covid-19 pandemic, yet they began before it, marking a major shift in America’s drinking habits.

But just how risky is the occasional wine, beer, or cocktail? Is moderation still the golden rule, or is every sip now a gamble? To find out, Columbia Magazine spoke with Katherine Keyes ’10PH, a professor of epidemiology at the Mailman School of Public Health and an expert on the health risks of our new drinking habits. Here’s what we learned.

Even moderate drinking poses risks

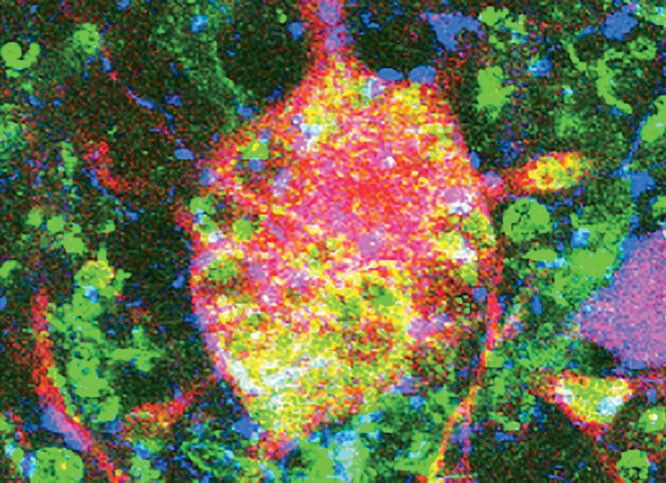

“A scientific consensus has emerged over the past couple of years that no level of drinking is entirely safe,” says Keyes. She notes that alcohol consumption has been linked to cardiovascular disease, numerous cancers, and accelerated aging, as well as liver disease. “And there’s a dose-response relationship, which means the more you drink, the higher your risk of these health issues.”

Keyes explains that for decades, researchers mistakenly believed that moderate drinking — defined as one drink a night for women, two for men — was beneficial, due to a blind spot in their studies. “Many people who don’t drink are choosing to abstain because they have health problems, which can make it look like moderate drinkers are comparatively healthy as a result of consuming alcohol,” she says. “But we now have methodological strategies to account for this and can see clearly that abstinence is the healthiest choice. Even moderate drinking raises the average adult’s risk of health problems by a small but detectable amount.”

Some people are at greater risk than others

Because public health studies describe trends across whole populations, it can be difficult to determine whether it’s safe for you personally to have a drink after work. Keyes says that friends and family frequently ask her advice about this. “I tell people that while drinking carries some risks for everyone, those risks are much higher for people with other health factors like obesity, smoking, weakened immune systems, or a family history of cardiovascular disease or cancer,” she says. “If you’re in good overall health and you don’t have these types of issues, there is low risk of significant health problems from moderate drinking, such as one drink per day.”

Binge drinking is on the rise, especially among women

One of the most concerning trends in recent years, Keyes says, has been an uptick in binge drinking among US adults, particularly women. Binge drinking — consuming four or more drinks within a few hours — intensifies alcohol’s toxic effects. And due to physiological differences, women are more susceptible to its negative impacts. Keyes’ research has found that drinking rates among women have steadily increased over the past few decades as more women have attended college, pursued careers, and delayed starting families. “The women driving this trend aren’t always the stereotypical ‘wine moms’ looking for stress relief,” she says. “They’re often highly educated, professional women drinking to socialize.” Keyes’ findings also show that people who binge drink in their youth often carry the habit into middle age, though typically at a less furious pace. “Our drinking habits tend to become embedded in how we socialize, manage our moods, and even choose partners,” she adds. “People who enjoy heavy drinking as part of their lifestyle often end up with partners who feel the same way.”

When in doubt, go “sober curious”

With growing awareness of alcohol’s health risks, a “sober curious” movement has recently taken off, especially among millennials and young adults. Supporters advocate for a mindful approach to drinking, often encouraging periodic pauses like “Dry January” or “Sober October” and less alcohol consumption overall. Keyes is a big fan. “When people cut out alcohol,” she says, “they often sleep better, feel mentally sharper, and have more energy.” She emphasizes that a successful shift toward sobriety often hinges on finding creative new ways to socialize and let loose. “One mistake that a lot of public health experts make is they assume that everybody who is drinking excessively is self-medicating for anxiety or some other mental-health issues, when, in fact, the main reason people say they drink is simply to have fun,” Keyes says. But whether it’s through mocktail meetups, outdoor activities, or game nights, there are other ways for people to party, hang out with their friends, and feel in the moment. “Turning the page on alcohol becomes easier when you discover new ways of connecting with people,” she says.

Simply cutting back can make a difference

If you’re concerned about how much you drink, Keyes recommends taking small, achievable steps to cut back. “If you usually have three drinks when you go out, try limiting yourself to two,” she suggests. “Any reduction in drinking is going to be beneficial to your health.” Keyes notes that even individuals with alcohol dependence may find they can regain control without having to quit entirely. “For a long time, people assumed that quitting was the only solution if you drank too much, but that’s not necessarily true for everyone,” she says. “New approaches, some of which include cognitive behavioral therapy, can help people understand their drinking habits and develop healthier limits.”