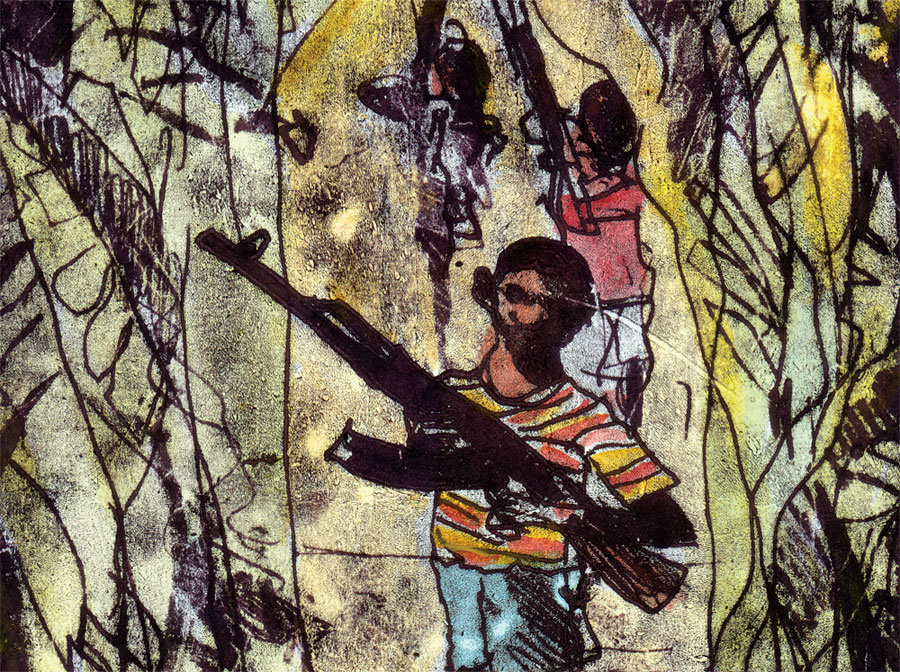

He started killing at 13. With an AK-47 that rattled his 100-pound frame, he ambushed government troops in a jungle swamp. He tortured war prisoners by shooting out their shins. He buried a man alive, kicked another to death, and using a move he'd seen in Rambo, slit a captive's throat.

Two years later he put down his gun, went back to school, and wrote a book about it. Possible? Former child soldier Ishmael Beah shocked the reading public this year with a blood-drenched memoir, A Long Way Gone, that's difficult to reconcile with its sensitive 26-year-old author. Reviewers puzzled over how Beah, who fought viciously for three years in Sierra Leone's civil war, could return from the moral void with his psyche apparently intact. "I don't think it's possible," wrote Carolyn See in the Washington Post, "to understand this book."

Beah's transformation didn't astonish everybody. Neil Boothby and Mike Wessells, both professors of clinical population and family health at Columbia's Mailman School of Public Health, have spent decades trying to disprove the misconception that child soldiers are hopelessly damaged. This view, they say, has led governments and even humanitarian agencies to neglect programs that can turn killers back into kids.

Today, Boothby and Wessells consult for humanitarian agencies that help thousands of escaped or captured young fighters reunite with their families every year. That's not easy because African paramilitaries often force children to commit atrocities in their own villages, precisely so they won't escape and head home. Yet, despite the stigma, the reprisals, and the psychological wounds, many of these kids will devote their lives trying to re-earn the trust of family members and neighbors.

"Children who go through the most horrific experiences will often bounce back, when given the opportunity," says Boothby, who directs Columbia's Program on Forced Migration and Health. "We've found there's always hope."

Innocence, weaponized

Child soldiering on a mass scale emerged in the lowlands of Mozambique in the early 1980s, when the rebel group Renamo, determined to destabilize the country's Marxist government, abducted thousands of desperately poor kids and trained them to terrorize civilians. Renamo leaders were good brainwashers, methodically indoctrinating the children into a culture of violence: If the kids wanted to eat, they could hack a cow to death. Those who cried too much or showed compassion were yanked aside to be executed. The tougher kids — they'd tell Columbia researchers later — got a choice: shoot the weaklings or be shot. The young killers were then initiated in quasi-spiritual ceremonies designed to sever family ties. They revered their commanders as new fathers and showed their obedience by slaughtering entire villages with farm tools and AK-47s.

When Mozambican troops liberated some of these little monsters, government health officials had no idea what to do with them, certain that their families wouldn't take them back.

Boothby was invited by the Mozambican government in 1988 to treat about 40 former Renamo fighters, from ages 6 to 16, who were being held in jails. He was then working as a psychiatrist at the humanitarian agency Save the Children and had previously counseled child rape victims and Cambodian youngsters who witnessed the atrocities of the Khmer Rouge. He agreed to set up a residential center for the boys in a Maputo convent. The kids who arrived a few days later were the most emotionally hardened children Boothby had ever encountered, and they were wild. "We put them to bed the first night and the next thing we know they're all screaming and sticking each other with knives they'd carved out of wood," says Boothby, 57. "It was like a Boy Scout troop gone bad, a real mess. You put yourself between two of those kids, and they're staring at you with those knives. That's intense."

Initially, the boys refused to talk to Boothby or his staff, which consisted of one Mozambican social worker and a few volunteers from a local women's community group. "The kids were very skeptical of our intentions," Boothby says. "Their attitude was, Now what are these adults going to do to us?" To start the boys talking, he asked them how they thought the center should be run. "I'd pose a question: 'What should be the punishment if someone doesn't make their bed?'" he recalls, "and I'm hearing stuff like, 'We'll tie him to a tree and you can hit him 25 times.'"

None of the boys had acute psychological conditions like schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or borderline personality disorder. Most showed signs of depression and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), but Boothby decided they didn't need medication. He wanted to treat the boys using methods that Mozambican social workers could eventually implement across the country in collaboration with traditional healers, or curandeiros. "A program like this could never be expanded to the necessary scale by parachuting in Western psychologists," Boothby says. "The front line of care would need to be the locals, and in this case, that meant the healers."

There was also a deeper issue: The children's long-term recovery, Boothby believed, would depend largely on emotional support the kids received after they'd gone home, support that would be offered only if the boys were treated in accordance with local customs. Western aid workers might look at a Mozambican child and see a case of chronic PTSD, but the boy would understand his suffering — and everyone he knows would understand it — as the result of his having angered ancestral ghosts. Therapy wasn't going to fix that.

Hell to pay?

Before the kids could return, Boothby would need to roll back their aggressive behavior, persuade them to trust again, and ease their most severe symptoms of anxiety, like flashbacks and recurrent nightmares. Every morning, the boys played soccer, did group art projects, prepared meals, and studied together. "We tried to make them feel like kids again," Boothby says. "We also wanted to get them out of their ruthless, survival-oriented mindset and get them cooperating with other people. It wasn't rocket science."

The boys were encouraged to discuss their experiences in Renamo, to draw pictures, and to write stories. Those who'd been soldiers for just a few months seemed to regard themselves as victims, retaining a sense of morality. "But there was a critical threshold of having served in Renamo for about six months to a year," Boothby says, "after which point the boys sort of lost their souls, perhaps out of self-preservation, and then it became much harder for them to return. We kept telling them over and over again that it wasn't their fault, and that they were still kids."

After six months of treatment, Boothby decided that all the boys were ready to leave. "There had been a slow evolution toward softer interactions," Boothby says. "We started to glimpse who these kids must have been before they were abducted. They were talking about loved ones they missed and saying things like, 'I want to be normal, like everyone else. I want to be a part of things again.'"

But were their families ready? Some of the boys had been gone for years and were presumed dead. Some had committed atrocities near their own homes. So Mozambican social workers, with guidance from Boothby and other psychologists at Save the Children, first visited their primitive, rural villages to explain what the boys had endured. They assured parents, teachers, and chiefs that the boys were no longer dangerous. The social workers also brought the parents, all of whom were subsistence farmers, food and farming supplies and education and health vouchers to ease the burden of having another mouth to feed. They offered financial assistance to families who couldn't afford a curandeiro's healing rituals, which can cost the equivalent of two months' salary in Mozambique, and they arranged apprenticeship programs to teach the older boys carpentry and masonry.

Boothby accompanied several boys home. He recalls his final conversations with them hiking along jungle paths, the heavy sacks of flour and sugar he lugged for the parents, the excitement that erupted in a village when a long-lost son and a tall, pink-nosed white man strode in. "And then the mother's eyes filling up with tears, the shouting, and the jumping up and down," he says. "Worth a lifetime, those moments."

A couple of boys were greeted coldly. The oldest in the group, 16-year-old Fernando, had commanded a Renamo squad that carried out attacks nearby. Relatives accused him of having killed some of their own, and they refused to allow him back in the village. The youngest, Quive, six, was taken in by his mother but shunned by his neighbors because, having spent years in the bush, he had no farming skills.

Most of the boys underwent elaborate healing ceremonies upon their return. A female curandeiro, her work typically subsidized by Save the Children, dipped a needle in chicken or goat blood and pricked a boy's arm. She bathed him in herbs and submerged him in water to expel the spirits of the people he'd killed. She contacted the boy's ancestral spirits, who watched over his family, to inform the spirits that the child had returned to his land. The ghosts had been confused when the children left, villagers believed, and that brought misfortune and shame.

Soldiering on

How would these boys turn out as adults? There was reason to worry. After the joy of the initial reunions, most remained emotionally troubled and some were harassed and attacked by neighbors for having fought in Renamo. But social workers who conducted follow-up visits in the early 1990s found that nearly all the boys were still living with their families and were either in school or working.

Save the Children expanded the program across Mozambique and humanitarian groups soon undertook similar efforts in sub-Saharan Africa, Southeast Asia, and South America, all areas where child soldiering escalated dramatically in the 1990s.

"Boothby's work with former child soldiers in Mozambique provided much-needed evidence of the impact of appropriate interventions," says Lloyd Feinberg, who directs the Displaced Children and Orphans Fund of the United States Agency for International Development. "Since the early 1990s, the U.S. government has increased its financial support for assisting in the rehabilitation and reintegration of former child soldiers significantly, and Boothby's work had a significant impact on the attitudes of decision makers within the government to make these investments."

Today, Columbia researchers consult for the nonprofits International Rescue Committee, Christian Children's Fund (CCF), Save the Children, and United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), on programs that assist child soldiers, all using methods that Boothby helped pioneer in Mozambique. Boothby and fellow public health professor Alastair Ager, for instance, spent time in Darfur recently to assist UNICEF in developing a plan to intervene on behalf of child soldiers in that region. Columbia faculty and students also travel among rural villages in Liberia, Northern Uganda, and Sierra Leone to investigate these questions: What can be done for child soldiers who aren't welcomed back by their families? How do you provide financial help to child soldiers without making their neighbors jealous? Do you support traditional healers who also perform clitoridectomies? How can parents prevent their children from being abducted by armed groups?

Much of the Columbia research involves analyzing data collected by local social workers. "I've learned to minimize the amount of direct contact I have with the child soldiers, because the locals are generally best suited to do that,Ó says Michael Wessells, who's been doing field work on children in war zones for the past 15 years. "Child soldiers can find it condescending for a foreigner to ask them too many questions. They look at me and think, So how many people have you killed?"

Wessells and doctoral candidate Lindsay Stark '06PH are collaborating now with Sierra Leonean social workers and CCF to assist thousands of young women who were abducted by paramilitaries and forced to serve as sex slaves and combatants in that country's civil war during the 1990s. Many girls came out of the war infected with HIV, having borne four or five babies, and were considered unmarriageable. Few accepted help from humanitarian workers for fear that they'd be ostracized as rape victims.

"A girl soldier faces much worse stigmatization after these wars than boys do," says Wessells, who wrote the 2007 book Child Soldiers. "If she finds a husband after the war, he's probably going to reject the babies she had in the bush. We know very little about how she'll support herself if she doesn't get married, or what happens to her babies if she does."

The things they carry

There's no doubt that some child soldiers are ruined. Many remain with warlords and criminal gangs as adults to earn a living, to retain positions of power, and for drugs, which they're fed from the time they're young, Wessells says. Cocaine addicted, mentally disturbed, and lacking skills, some travel long distances to join new wars when conflict in their own country ends, he says. Ishmael Beah, after all, was the rare youngster who, having lost his family, was taken in by Westerners; many of his friends returned to the front lines in Sierra Leone after being liberated with Beah by UNICEF, he writes in A Long Way Gone.

Indeed, many policy makers assume that child soldiers will grow up to be career criminals and social outcasts, say Boothby and Wessells. The two professors regularly lobby governments to give more money to humanitarian agencies for rehabilitation and reintegration programs. "Officials in Western donor countries, and even in the places where these atrocities occur, generally have a demonic image of these kids," says Wessells, who is a child protection officer at CCF and cochairs a United Nations task force on mental health in emergency settings. "After the fall of the Taliban in Afghanistan, for example, child advocates pushed really hard to get UN assistance for boys who served under warlords. The funds didn't come through, partly for this reason. That happens a lot."

There's also debate within the NGO community about how best to spend money to help trauma victims in war zones and at natural disaster sites. The predominant view at most large humanitarian agencies, Boothby and Wessells say, is that emergency psychotherapeutic care that adheres to Western standards should always be the top priority, usually at the expense of more culturally targeted, long-term reintegration projects. Boothby and Wessells are among a smaller group of researchers trained in social work or public health who believe that trauma victims typically need help finding housing, locating relatives, and earning money more than they require psychotherapy. Traditional healing ceremonies, these researchers argue, allow people in non-Western cultures to meet their basic needs.

Proponents of this perspective got a big boost last year when Boothby published follow-up research on the Mozambican boys he helped 18 years ago. Appearing in the journal Global Public Health, it was the first study to follow former child soldiers for more than five years. The results are startling: These men, on average, earn substantially more than other men in their villages today, with many taking extra jobs in nearby townships to supplement their corn and bean farming; they are loving husbands and fathers whose kids are 15 percent more likely to attend school than the typical Mozambican child their age; and they're more likely than the average Mozambican man to own a home.

Even Boothby can't explain the results. Asked if perhaps only type A personalities survive the child-soldiering experience, Boothby pauses to think. "That's an extremely interesting question," he says. "I don't know. I was certainly surprised by the findings. Most psychologists don't know what to make of it."

Fernando, the 16-year-old who had been a powerful Renamo commander, was never able to acclimate to civilian life. "One night he was out of town bragging about his Renamo days," says Boothby. "He got in a fight with a cop and was shot dead." The youngest fighter, Quive, just four years old when taken by Renamo, was mute for much of his youth. As an adult, neighbors say, he was a compulsive liar. He accidentally drowned in 2003.

But most of the men live relatively normal lives, despite their demons. Several can't use machetes without being reminded that they tortured people, so their wives slaughter animals on the farm. One man doesn't drink with friends because boisterous gatherings give him flashbacks. Another avoids a particular jungle path where, as a child, he saw severed heads on stakes. In other words, they cope.

"The men constantly mention the healing rituals when asked about their recovery," says Boothby. "They use terms to describe how they felt afterward that can best be translated as sane."

For lawless wars, the ultimate fighters

Youngsters have always played minor parts in war. Child "charioteers" rode into battle alongside Greek warriors, 12-year-old squires accompanied medieval knights, and in the early modern era, drummer boys took bullets, as did young powder monkeys who helped load cannons on warships. The Nazis drafted adolescents to defend Berlin in the spring of 1945, and both sides in the Iran-Iraq War forced 10-and 11-year-olds to clear minefields in the 1980s.

But something different started happening about 25 years ago. Across sub-Saharan Africa, as well as in parts of Southeast Asia and South America, entire paramilitaries composed of young fighters appeared. What happened? The story of Mozambique's feared rebel group Renamo illustrates the societal forces behind the phenomenon, says Columbia public health professor Neil Boothby, who was among the first psychologists to rehabilitate child soldiers in that country. First, Renamo had no strategy to rule politically in the 1980s and early 1990s, as it was backed by foreign colonial forces determined merely to undermine Mozambique's newly independent government, Boothby says. Renamo aimed to accomplish this by terrorizing civilians, which didnÕt require a standing army. And because Mozambique had endured civil war more or less since the 1960s, depleting the numbers of men available to fight, Renamo abducted vulnerable kids, who proved to be malleable and fearless warriors, especially when coked up on drugs.

Similarly ugly conflicts spread across Africa at the end of the Cold War, New York Times East Africa bureau chief Jeffrey Gettleman has observed, as unstable nations once propped up by the United States or the Soviet Union collapsed. This created a power vacuum filled by warlords who aspired not to moral legitimacy but merely to foment enough chaos that they'd be left alone to plunder diamonds, copper, drugs, or timber. Around the same time, Western and ex-Communist countries sold off huge arms surpluses, flooding poor countries with cheap guns like the AK-47, which is so lightweight that a typical 10-year-old can shoot it.

"Boys in some traditional African cultures are considered men at age 12, so adolescents had been called to fight in the past," says Boothby. "But these new conditions took the phenomenon to a much, much larger scale."

There are now 300,000 children under the age of 18 serving in militias around the world, according to the United Nations. Most child soldiers are adolescents, but many are much younger. Typically they are abducted, although young orphans and refugees in war zones sometimes join armed groups to survive, says Michael Wessells, a Columbia public health professor who studies children in war zones.

Child soldiering has fueled some of the world's most long-running and barbaric conflicts: Ugandan government troops and rebels have combined to abduct 30,000 children over the past two decades, teaching them to pound the skulls of newborns in wooden mortars; all sides in Congo's civil war exploit children, who have been reported to eat their victims' flesh; and tens of thousands of kids fight for government and rebel paramilitaries in Darfur, the Philippines, Nepal, Sri Lanka, and Myanmar, as well as for Colombian militias that control that country's drug traffic.

Boothby, Wessells, and other child-welfare experts have succeeded in putting the issue on the United Nations agenda. The UN in recent years has earmarked tens of millions of dollars to disarm and rehabilitate child soldiers, assigned child protection experts to UN peacekeeping operations, and passed protocols that make it illegal for combatants to be less than 18 years old.

But these measures have largely fallen flat. United Nations programs that pay militias to disarm, while purportedly aiming to identify and rescue child soldiers, are "extremely un-child- friendly," says Boothby. Warlords often abduct children precisely to hand over to peacekeepers in exchange for cash, he says, and many peacekeeping operations have required kids to turn in guns to get assistance, which neglects boys and girls who serve militias strictly as servants, spies, and sex slaves.

Meanwhile, "people that recruit child soldiers aren't being punished," Boothby says, "and Western countries still sell guns to them, even when everybody knows they're going straight into the hands of eight-year-olds."