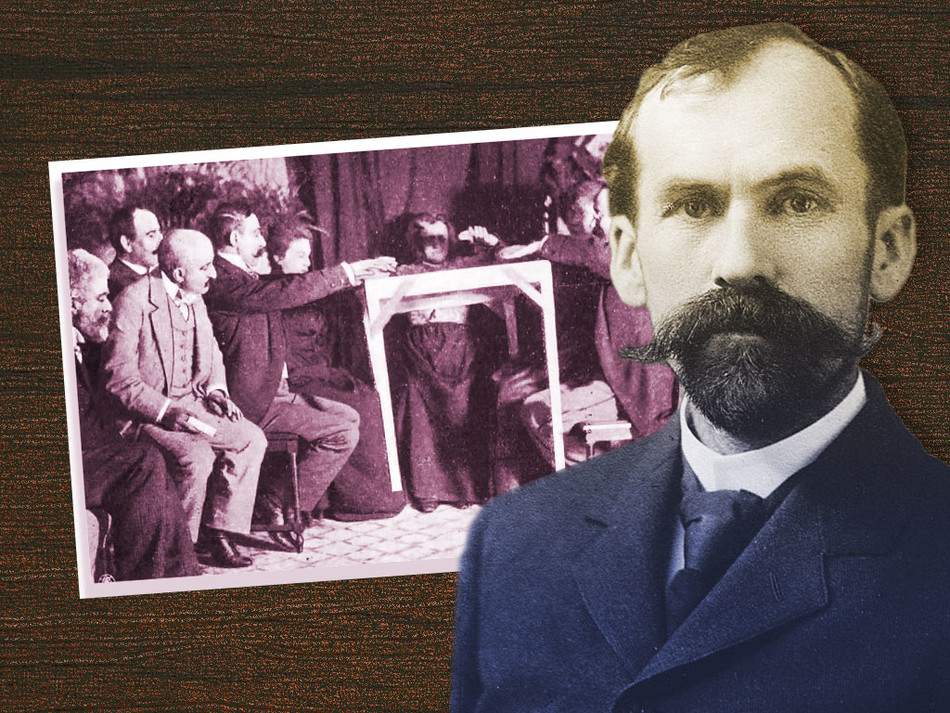

On November 14, 1909, Eusapia Palladino of Italy, having arrived by ship to New York, traveled uptown to the Lincoln Square Theater. There, before a crowd of reporters, impresarios, and Broadway celebrities, the world’s best-known psychic medium showed off her famous ghost-rousing, table-shaking powers. Days later, at Columbia, Samuel Hershenstein 1911LAW caused a stir of his own: he, too, claimed to have special powers that allowed him to make a table jiggle, jump, tilt, and levitate. To prove it, he invited students and faculty members to a demonstration in Earl Hall.

Such exhibitions were not uncommon at that time. Spiritualism, a quasi-religious movement couched in the belief that the living can communicate with the dead, was at its peak of popularity, embraced by millions of middle- and upper-class Americans. Prominent intellectuals like William James, the great philosopher and psychologist, and James Hyslop, a professor of ethics at Columbia and president of the American Society of Psychical Research on West 73rd Street, insisted that paranormal phenomena — telepathy, clairvoyance, levitation, and the like — deserved rigorous scientific study. And though every so often some sleuthing reporter would unmask a fraudulent medium through discovery of hidden apparatus, Hyslop never wavered: to him, these debunkings disproved nothing, and confirmed what he already knew, which was that the parapsychic world was not immune to charlatanism.

In Hyslop’s view, the problem with a vaudeville-inflected Spiritualist like Palladino was that she provoked skepticism in intelligent people and closed their minds to what might be genuine. “If these seances had been given quietly before an audience of scientists,” Hyslop told the Spectator at the outset of Palladino’s US tour, “the present storm of prejudice would never have arisen, and some real results might have been gained.”

Hershenstein did not identify as a Spiritualist, perhaps wanting to distance himself from a movement whose reputation was diminished each time a muckraking newsman crawled under a séance table and spotted invisible strings. As he explained it, he simply had this strange and baffling ability to tilt tables. Posing as a helplessly gifted innocent in the thrall of powers he didn’t comprehend only enhanced his credibility.

He was also a good promoter. Some seventy people showed up to his séance in Earl Hall on November 19, 1909. According to the Spectator, Hershenstein and his brother, Charles, also a law student, set up the table, and ten students sat around it. The students laid their hands on the tabletop, and after about twenty minutes, Hershenstein asked the table to rise. The table rose, fell, reared up at angles, all without any apparent physical intervention. “At no time during the entire séance did anyone in the room touch the table other than those who were seated at it and their hands alone were on it or touching it,” the Spectator stated. “When asked afterwards to explain his power over the table, Hershenstein said that he was unable to explain it in any way.”

Days later, Hershenstein gave an encore performance. Again, the Spectator was credulous: “He performed some of his previous feats and attempted several new experiments with great success. At his command the table danced from side to side, stood on one leg at an angle of about forty degrees and rose and fell alternately.” The report ended on an intriguing note: “As Hershenstein has promised to give a demonstration of his powers to Spectator’s staff very shortly, he intends to invite Professor Hyslop to attend. After the séance he will endeavor to explain to the professor the causes of his mysterious power which he himself does not fully understand.”

Hyslop, a leading scholar of the occult, had heard about the Earl Hall seances and was eager to see one firsthand. “We cannot explain the phenomena of table-tipping, but we are positive that such phenomena exist,” he told the Spectator. “Accordingly, I am very glad to obtain any new data on the subject, and this performance at Columbia interests me greatly.”

Hershenstein, meanwhile, having satisfied the school paper, turned to bigger game. He planned another séance in an office building on Lower Broadway and invited the city dailies, including the New York Times. “Our sole purpose in asking you to attend this séance,” he wrote to the editors, “is to convince you that our exhibitions are free from trick or device.”

A dozen reporters showed up for the event, and they were all instructed to sit down and place their hands on the table. The Times described the spectacle: “The table did some fine stunts. It stood on one leg, then on two legs, and then it jumped up and then leaned way over as if it was tired and wanted to go to sleep.” Despite the presence of skeptical newsmen, no trickery was exposed. “Nobody,” the Times wrote, “saw what made the table perform.”

The next test for Hershenstein was Professor Hyslop, a true believer who stood to gain more than anyone if he found the demonstration to be legitimate. Plans were made, but in December 1909, the Spectator reported that the séance was postponed until after the Christmas holiday due to Hyslop’s schedule. Strangely, that is the last mention of the Hershenstein seances. There is no further reporting that this highly anticipated séance ever took place — which strongly suggests that it didn’t.

So what happened? Could it be that Hershenstein, having already gone so far, was wary of Hyslop’s scrutiny and chose to quit while he was ahead? After all, Hyslop was the man who once wrote that “the primary difficulty” in psychical research “is the contest with public frauds,” and that those who “wish to exploit human credulity have no scruples.” Had Hershenstein found his scruples and quit the game?

And what had motivated him and his brother in the first place? Were they pranksters? Showmen? Audacious performance artists? Were they experimenting, in their capacity as law students, with theories of persuasion, forensics, group psychology? Or — not to entirely exclude the possibility — were they authentic mediums? No judgment has been recorded. But what is certain is that Samuel Hershenstein did not suffer the bitter fate of Eusapia Palladino.

That unfolded in the spring of 1910, when one of Hyslop’s colleagues at Columbia, the philosophy professor Dickinson Miller, who had studied under William James at Harvard, took matters into his own hands. To Miller, the act of knowingly leading others into false beliefs, as he suspected Palladino of doing, was a grave moral crime, and in exposing her methods he wanted to leave no stone — or table — unturned. He arranged several table sittings with Palladino, in his apartment and on campus in Fayerweather Hall. To achieve his goal, Miller had to deploy some deception of his own: he hid several “spies” in the rooms where Palladino was operating.

Miller and his spies determined Palladino to be a master of misdirection who shrewdly and subtly used her feet, hands, and breath to achieve desired effects. “Her art is to obtain credence under false pretenses,” Miller wrote in a devastating takedown in the Times titled PALLADINO TRICKS ALL LAID BARE. In her defense, the cornered Palladino claimed that if she did resort to trickery, it was only because the investigators had placed the idea in her mind telepathically. Her reputation did not survive Miller’s pen.

As for Hyslop, the Miller-Palladino affair hardly dissuaded him from his pursuits — he’d never taken Palladino seriously anyway. There were plenty of other psychic phenomena that needed to be studied. “Spiritual psychology is still in its infancy,” he said in 1909, and he did all he could to advance it into its next stage of growth. He died in 1920 from a blood clot after a long illness brought on, some believed, from the intensity of his labors.

Samuel Hershenstein died in 1971 at age eighty-five. After law school he became assistant district attorney for the Southern District of New York. In 1918, the year of Palladino’s death, Hershenstein and his wife, Edith, moved to Washington, where he worked in military intelligence during the last year of World War I. Afterward he returned to New York. Whether or not he continued to tilt tables is unknown, but he and Edith did settle at 23 West 73rd Street — right across from the American Society of Psychical Research.