In 1914, when the English journalist Edward Thomas confessed to his American friend Robert Frost that he wanted to write poetry, Frost informed him that he was already doing so. “Right at that moment he was writing as good a poetry as anybody alive,” Frost would recall, “but in prose form where it didnt [sic] declare itself and gain him recognition.” Frost suggested that Thomas take the rich descriptive sentences in his book In Pursuit of Spring and recast them in verse lines of “exactly the same cadence.” Thomas obliged, and in the three years before his death in World War I created poems of surpassing, and surpassingly quiet, beauty. Here’s his memory of a midsummer whistle stop in a Cotswold village:

The steam hissed. Someone cleared his throat.

No one left and no one came

On the bare platform. What I saw

Was Adlestrop — only the name

And willows, willow-herb, and grass,

And meadowsweet, and haycocks dry,

No whit less still and lonely fair

Than the high cloudlets in the sky.

And for that minute a blackbird sang

Close by, and round him, mistier,

Farther and farther, all the birds

Of Oxfordshire and Gloucestershire.

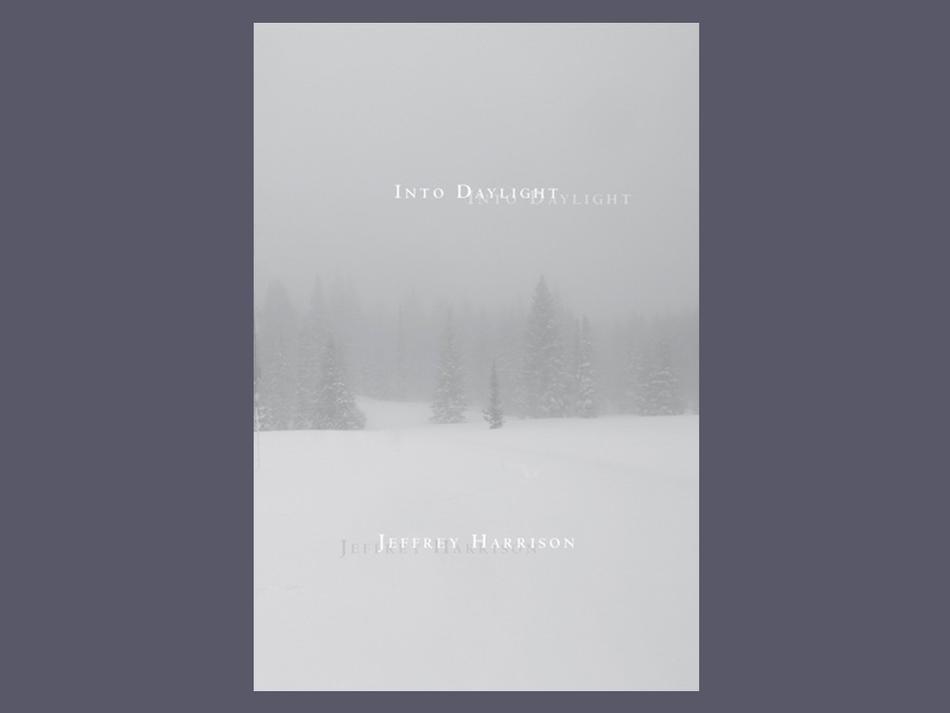

An homage to Edward Thomas appears about three-quarters of the way through Into Daylight, Jeffrey Harrison’s new book of poems, by which point it seems almost inevitable. Harrison ’80CC is a poet in enthusiastic pursuit of Thomas’s project — turning to the natural world for restoration and insight, and sharing his findings in an elegant plain style so understated it could be mistaken for no style at all. The conversational opening lines of “Vision” seem almost indifferent to their identity as lines; they sound more like a letter to a friend:

I just got back from the eye doctor, who told me

I need bifocals. She put those drops in my eyes

that dilate the pupils, so everything has

that vaseline-on-the-lens glow around it,

and the page I’m writing on is blurred

and blinding, even with these sunglasses.

I’m waiting for the “reversing drops” to kick in

(sounds like something from Alice in Wonderland),

but meanwhile I like the way our golden retriever

looks more golden than ever, the way the black-eyed

Susans seem to break out of their contours, dilating

into some semi-visionary version of themselves,

and even the mail truck emanates a white light

as if it might be delivering news so good

I can’t even imagine it.

There’s a lot to notice, or fail to notice, here: the loose blank verse; the way the black-eyed Susans dilate to match the speaker’s eyes; the way the passage itself dilates, each sentence almost exactly twice the length of the one before it; the way the poem’s apparent spontaneity and immediacy are made possible by a series of carefully considered phrases — “the page I’m writing on,” “these sunglasses,” “I’m waiting”; the way the dog changes when the word “golden” is repeated, from a mere example of its breed to something almost beatific; the way “the way” is repeated, too — an anaphor that nudges the writing from conversation toward incantation; the way all of this bespeaks a poem shifting by degrees from the prosaic to the lyrical without really seeming to change, as a seagull on the sidewalk becomes a seagull in flight.

Harrison has been doing this for three decades now. Into Daylight, his sixth collection, finds him taking stock at midlife — trying to emerge from a long personal darkness that followed his brother’s suicide, to transcend pettiness and disappointment, and to find steadying consolation in love, memory, and art. He likes to build his poems around single, slow-developing conceits and to tease big implications out of small domestic incidents. In “The Day You Looked Upon Me as a Stranger,” Harrison’s wife spots him at a distance in the airport, doesn’t immediately recognize him, and admires his appearance:

I wondered if you had pictured him

as someone more intriguing than I could be

after decades of marriage, all my foibles known ...

did you imagine a whole life with him?

and were you disappointed, or glad, to find

it was only the life you already had?

More than anything, Harrison likes to write clearly and directly — or, rather, with apparent clarity and directness. He strips the lyric voice of flourish and ornament and allows it to simply speak, which is not the same thing as speaking simply.

Yes, yes, you can’t step into the same

river twice, but all the same, this river

is one of the things that has changed

least in my life, and stepping into it

always feels like returning to something

far back and familiar, its steady current

of coppery water flowing around my calves ...

Occasionally he chases artlessness with such determination that he catches it, failing for a few lines to distinguish between the pleasingly idiomatic and the merely trite: “all the petty injustices that have gone on / since ancient times and are bound to continue / for centuries to come.” And his campaign against grandiosity can at times lead to a reflexive self-effacement that only further foregrounds the self. When, with clever enjambment, he describes his vocation as “sitting at the kitchen table doing what / any respectable carpenter would call / nothing,” he’s being funny, undeniably, but he’s also doing what any respectable reader would call caricaturing carpenters.

Far more often, though, his common diction and uncommon intellect reconcile in a poem of exquisite lucidity. Harrison has a nose for nouns like “Vision,” whose multiple meanings include both the sublime and the ordinary, suggesting the presence of the sublime in the ordinary. A poem called “Renewal” takes place at the DMV and contains the lines, “But when I paused to look around, using my numbered / ticket as a bookmark, it was as if the dim / fluorescent light had been transformed / to incandescence.” Then there’s “Temple,” a tiny love lyric:

Not a place of worship exactly

but one I like to go back to

and where, you could say, I take

sanctuary: this smooth area

above the ear and around the corner

from your forehead, where your hair

is as silky as milkweed.

The way to feel its featheriness best

is with the lips. Though you

are going gray, right there

your hair is as soft as a girl’s,

the two of us briefly young again

when I kiss your temple.

This is a book full of quiet triumphs, a daylight you can step into repeatedly but not twice.