“The Little People,” a fable-like story in Disruptions, the latest collection by Steven Millhauser ’65CC, the narrator describes what so enchants a town’s regular-size inhabitants about their two-inch-tall counterparts: “What fascinates us is the sense of an invisible world perpetually on the verge of becoming visible.” The same might be said about the experience of reading a Millhauser short story. In the author’s hands, the familiar — the dawn of summer in an American suburb, a high-school English lesson, a late-night walk — transmutes, unmasking the surreal lurking under a placid surface.

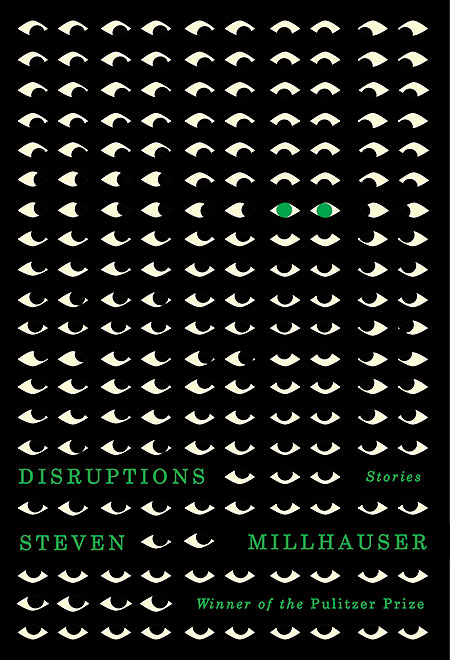

Millhauser may be best known for his novel Martin Dressler, which won the Pulitzer Prize for fiction in 1997, but to avid fans, he is an underappreciated master of the short story, earning comparisons to the likes of John Cheever and Jorge Luis Borges. The author has characterized the form as “unassuming in manner,” concealing a secret ambition: to contain a world in a Blakean grain of sand. Across nine previous collections, Millhauser has proven his skill at crafting meticulously detailed worlds in miniature — uncanny microcosms that expose the faults of the American way of life. Disruptions, which brings together eighteen stories, demonstrates that the master’s gifts have only sharpened with time.

Many of the stories in Disruptions take place in the suburbs — specifically, in virtually identical small towns in the author’s home state of Connecticut. These quiet suburbs, the kinds of places with “tree-lined streets and green lawns,” seem the embodiment of the American dream, until some oddity punctures the perfection.

In “The Little People,” the disruption comes from a clash between the two groups within the town. What begins as a humorous series of encyclopedia-like entries on this tiny race develops into a meditation on the difficulties of connecting across difference. In this town, the risks of integration are tangible: Little People may be gravely harmed by “our monstrous children, our cats and dogs the size of buffalos, our sneezes like windstorms.” Among the bigger people, the presence of the Little People triggers philosophical turmoil: “They are like us in every way, except one. It is this difference that creates unease and fascination in equal measure. If, by some miracle of science, they could suddenly grow to our size, we would experience a terrible sense of loss, though exactly what would be lost is difficult to say.”

This experience of an overwhelming feeling or urge that transforms the local order permeates a handful of other stories. In these, the disruption comes when a suburb is taken over by groupthink, in some cases more seemingly benign than others. “Theater of Shadows” sees the town suddenly enamored with “those creatures born of the sun, but rebelling against the light” — shadows — in a sort of reversal of Plato’s allegory of the cave. In “The Summer of Ladders,” a fad spreads of erecting and climbing taller and taller ladders in the town’s meticulous yards. In “Green,” the townspeople tear up those yards, replacing them with elaborately patterned stones or tiles. In each story, new businesses and products spring up to capitalize on — and spur — the frenzy; in each story, consumption fails to satisfy, even as it reaches new extremes. If the structure and conceit repeat, the revelations don’t diminish.

At other times, Millhauser zooms in on individual members of the community, studying moments that change their lives irreparably. The most fantastical is in “Kafka in High School, 1959,” a tour de force that imagines the novelist as an American teenager, his famous anxieties centering on a blond girl in his AP English class. Quieter but no less ambitious is “The Change,” a pitch-perfect inhabitation of the mind of an adolescent girl walking home alone at one in the morning, each long sentence capturing the simultaneous freedom and unease she feels. We await a predictable horror, but this is a Millhauser story — even if nothing bad happens, strangeness lingers.

With each story in Disruptions, Millhauser trains the reader to brace for some bizarre intrusion into our reality. The pleasure comes from seeing how far he can stretch boundaries before they ricochet back into place.