In 1929, the mayor of Berlin visited Manhattan and was reported to have jocularly asked Mayor Jimmy Walker when Prohibition, legally in effect since 1920, would begin. On the evidence of eye or tongue, no tourist, from Berlin or Mars, could have thought Manhattan dry.

New York was the perfect storm for the nullification of what in 1928 Herbert Hoover called “a great social and economic experiment, noble in motive and far-reaching in purpose,” giving rise to the enduring misquotation “the Noble Experiment.” Hoover, highly intelligent and literate, claimed for Prohibition a noble intention, but he must have known that such intentions were often recycled as paving.

Prohibition’s roots were in the small towns. Among these was Westerville, Ohio, the headquarters of the quaintly named Anti-Saloon League. Your reviewer, who spent his first seven years in Westerville, remembers being dandled in the late 1930s on the knee of Howard Hyde Russell, the League’s founder, a kindly old gentleman still much honored there even after the calamity of Repeal. But the League’s lobbying operation was neither kindly nor quaint; brutal is the word. The League secured the Eighteenth Amendment by supporting legislators who could stagger to the floor and vote dry, and by defeating total abstainers, who voted wet.

New York was no Westerville: As a great city it was an improbable site to implement the social vision of the Westervilles, and, as the kind of city it was, an impossible one.

Michael A. Lerner ’89CC, an associate dean at Bard High School Early College, has written a lightly learned and perceptive account of Prohibition in New York that centers on the particularities of the city while casting informative light on Prohibition in general. As he makes clear, the fight over dry laws was to a large extent a civil war between the totally assimilated, almost deracinated, descendants of pre-Revolutionary immigrants and post-Revolutionary immigrants and their descendants.

New York was peopled by ethnic minorities (in aggregate, the majority) for whom the substances banned under the Volstead Act, the legislation enforcing the amendment, were woven into the quotidian fabric. Whether the ban was on wine (for the Italians and Jews), beer (for the Germans and Central Europeans), or whiskey (for the Irish), it represented an unexpected pothole in the golden pavement. Few New Yorkers wanted the experiment to succeed.

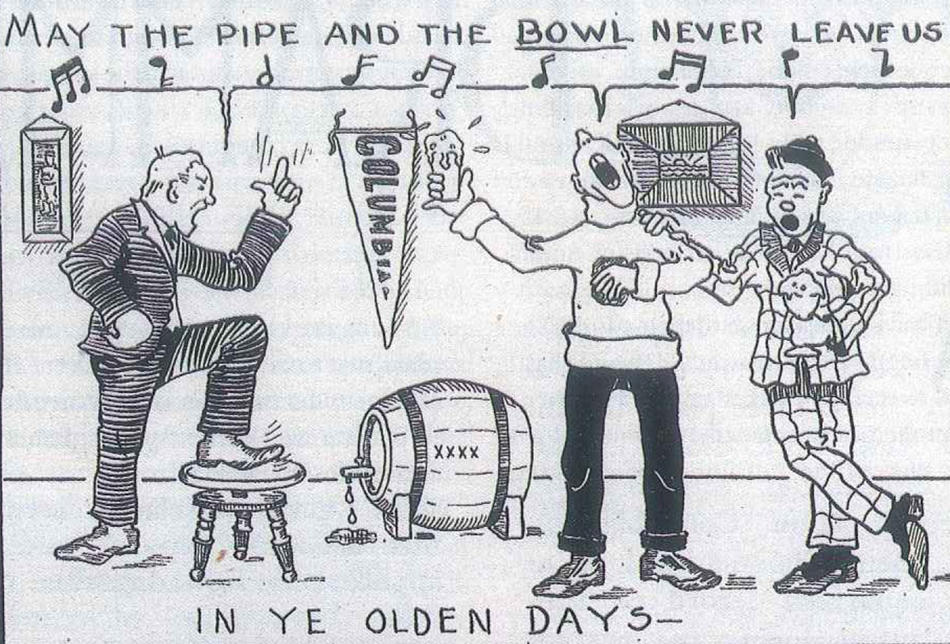

Last, there was the fact that except between April 5, 1921, and June 1, 1923, New York, unlike other states, had no Prohibition law of its own. The onus of enforcement was on the feds and the agents of the Bureau of Prohibition, who even when not outsourced to the Keystone Studios, were not models of probity: Some went so far as to open establishments and sell confiscated liquor. Although the bureau tried to enlist New York’s finest in the cause, results were mixed. Tammany Hall was wet. Moreover, Prohibition midwifed alluring venues for demon rum unimagined in Westerville. The saloon acquired a formidable and more elegant competitor.

“The variety of New York’s Prohibition-era drinking spots was mind boggling,” writes Lerner, with the most prolific form being the speakeasy, “a catch-all phrase for illegal bars ranging from cellar dives peddling 25-cent beers or 50-cent glasses of ‘smoke,’ to fancy townhouses in midtown outfitted with multiple bars, dining areas, game rooms, and live entertainment. Speakeasies could easily be hidden in storefronts, office buildings, or apartment houses…. In fact, part of the appeal speakeasies held for New Yorkers seemed to be the unpredictable nature of their locations. …As one English observer noted, the culture of the Prohibition era ‘raised drunkenness in America from a vice to the dignity of a sport.’”

One wonders why Repeal took so long. Lerner reports that all the evidence, available almost from the start, indicated that Prohibition did not work and introduced serious unforeseen consequences, including much increased rates of murder and hospitalization for alcoholism. Lerner attributes the delay to a general belief among Prohibition’s supporters that it just needed a chance — perhaps a surge in enforcement — and a worry among the politically alert that Repeal was the third rail of politics. The latter were right. In 1926, the Anti-Saloon League easily retired James W. Wadsworth, Jr., senator from New York, a Republican fixture but a wet, and provided much of the muscle to defeat Al Smith in 1928. The League cared less about Al’s Catholicism than about his wetness, but his faith provided the more useful club.

Two prominent New York Republicans early discerned the failure of the experiment and supported Repeal. One was Congressman Fiorello La Guardia, who made a drinkable and legal tipple by mixing nonalcoholic beer with malt tonic. He conducted tastings for the press in his congressional office and on a sidewalk in his East Harlem district.

His colleague was none other than Nicholas Murray Butler, who concluded that Prohibition was not merely a perverse failure but likely to drag the GOP down with it — a prescient judgement. President Butler’s campaign to make Repeal a bipartisan issue crowned his career as a public intellectual.

The defeat of Al Smith in 1928 led many to believe that Repeal, or even moderate change, was impossible. As late as 1930, William Howard Taft gloomily opined that the Eighteenth Amendment was safe for all time.

Yet crime and alcoholism continued to mount. Hoover appointed a commission to study the matter. Its five-volume report documented the failure but recommended staying the course.

And then the locomotive of history, in the form of the Depression, hit Prohibition and the party that still favored it. The 1932 Democratic convention adopted a straightforward Repeal plank, and Franklin D. Roosevelt perceived that the third rail had been turned off.

The end was quick. The second major bill of the New Deal amended the Volstead Act to allow the sale of beer and wine. By the end of 1933, the Twenty-First Amendment had been ratified by the requisite number of state conventions. (Lerner erroneously says that the amendment was “speeding through state legislatures”: The constitutional option of ratification by convention was chosen to spare state legislators, who might worry that the third rail was still live.)

Writing about Prohibition at its start in Babbitt (1922), Sinclair Lewis treated it as an extinct folkway needing glossing. Lerner explains this extinction:

“New Yorkers who opposed Prohibition rejected the idea that the state had a right to dictate the private conduct of its citizens. … [T]he dry crusade … was an affront to their values and their identities as Americans. … [They] defied the Volstead Act as a way of saying that the diverse culture and cosmopolitanism of the modern city was their American ideal. … New Yorkers helped steer the nation … towards both a more tolerant view of American society and a more practical understanding of the relationship between the government and its citizens.”

Told authoritatively and lucidly, this is the story of the city that just said No.