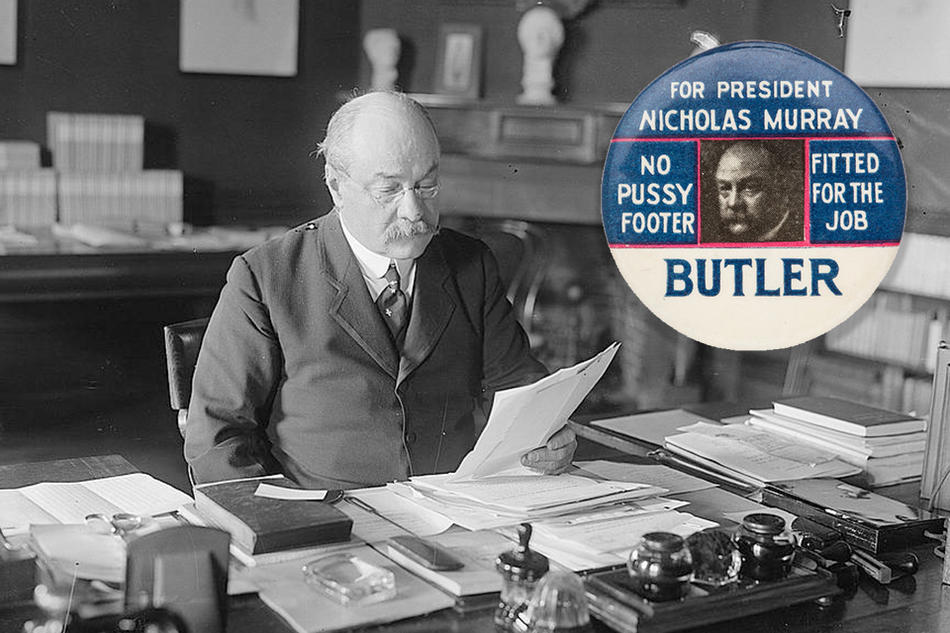

These days, the outcome of national political conventions is all but predetermined: a candidate prevails in the primaries and is formally chosen by delegates to become a party’s nominee for the presidency. But delegates weren’t always bound to primary results. Take the 1920 Republican National Convention in Chicago, when no fewer than eight aspirants, including Columbia president Nicholas Murray Butler 1882CC, 1884GSAS, arrived at the Chicago Coliseum hoping be chosen. That year, with delegates split and many undecided, the contest was up for grabs; and if anyone was confident of victory, it was the Sage of Morningside Heights.

One of the nation’s most celebrated public intellectuals, Butler also saw himself as its savior, and his lofty sense of destiny convinced him that the populace would concur. Amid the First Red Scare, Butler had spent months speaking to political clubs across the land, warning of “elements in our population” who “frankly proclaim their preference for the political philosophy of Lenin and Trotsky to that of Washington, Hamilton, Webster, and Lincoln.” In an acquired patrician elocution that turned “America” into “A-mad-ica,” Butler called for a revival of patriotic ideals, lest the nation succumb to a “social democracy” that would “take over the management of each individual’s life and business.”

While Butler sought to reinstate conservative mercantile values in a world slouching toward Bolshevism, dignity required him to stay above the political scrum. So he conducted what his biographer, Michael Rosenthal ’67GSAS, calls a “stealth campaign.”

“Butler was clearly running for president, but he didn’t want to draw attention to it,” says Rosenthal, a professor emeritus of English and the author of Nicholas Miraculous: The Amazing Career of the Redoubtable Dr. Nicholas Murray Butler. “He didn’t run in the primaries, he didn’t want to raise money, which he found demeaning, and he didn’t want to be attacked by other candidates.”

Among the Republicans vying to face Woodrow Wilson, the Democratic incumbent and former president of Princeton, were Illinois governor Frank Lowden; Major General Leonard Wood, a Harvard-educated Army surgeon; Hiram Johnson, an isolationist California senator; and Ohio senator Warren G. Harding, notable for his candid lack of intellectual depth. In such a field, Butler liked his chances.

The son of a middle-class textile manufacturer, Butler was born in Elizabeth, New Jersey, in 1862, and raised in Paterson. At Columbia he earned a doctorate in philosophy, became a professor, and succeeded Seth Low as University president in 1902. Driven by what Rosenthal describes as an “insatiable need for power and recognition,” Butler wooed the rich and influential, displayed autocratic tendencies that divided both faculty and students, and led Columbia’s rise from a small, local school to the largest university in the country. President Theodore Roosevelt 1899HON dubbed him “Nicholas Miraculous” for his wondrous energies, and 1920 campaign circulars touted a “man of sterling courage” who “has rubbed shoulders with presidents, governors, diplomats, statesmen and the big men of the nation.”

But as Rosenthal tells it, Butler’s path to the White House faced two major hurdles. The first was image: after eight years of Wilson, voters weren’t clamoring for another college president. So Butler enlisted a press agent who created an alternative persona to the book-stuffed Butler of the Acropolis on the Heights. Campaign leaflets mocked Wilson as “the schoolmaster type of college president” while casting Butler as “the executive head and chairman of the Board of Trustees of a tremendous educational and financial institution conducted along the lines of a business enterprise.” Columbia was no “scholar factory,” the pitch went. It was a “citizen factory.”

Rosenthal finds a poignant sadness and absurdity in this depiction. “To claim that Butler was the president of a university that did not produce scholars was ludicrous. But that was the trap Butler was in.”

He was trapped, too, says Rosenthal, by his “totally narcissistic personality”: electoral failure was so inimical to Butler’s grandiose vision that he made self-defeating choices — not raising money, not hiring savvy political operators — in order to claim, in case he did lose, that he had never fully tried to win.

Still, Butler trusted that delegates in Chicago would “Pick Nick,” as his slogan implored, to run against Ohio governor James M. Cox, who had replaced an ailing Wilson. On June 8, 1920, Butler arrived at the Chicago Coliseum, buoyed by reports from his handlers of a Butler groundswell. But after four nights, no Republican candidate had reached the necessary 471 votes. And so a group of senators huddled in a smoke-filled hotel room and agreed to shift the majority of votes to the Ohioan, Harding.

“Butler was hoping till the end that things would go his way,” Rosenthal says. “He never withdrew.” After the final ballot, Butler had just two delegates. “It was the greatest loss of his career,” says Rosenthal, but he “maintained the idea that he didn’t really lose for the rest of his life.”

After the election, Butler moved on. Retaining his Columbia presidency, he also became president of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace in 1925 and president of the American Academy of Arts and Letters in 1928. In 1931, Butler won the Nobel Peace Prize for his work to strengthen the International Court at The Hague.

Later portraits of Butler show a silver-browed man in grandfatherly repose, the sort of venerable old philosopher who fondles a watch chain while quoting Aristotle. He retired from Columbia in 1945 and died two years later. His memorial, held at St. Paul’s Chapel, drew hundreds of mourners. Among them was the next Columbia president, Dwight D. Eisenhower, who would win the Republican nomination in 1952 and become, as Butler had not, president of the United States.

This article appears in the Spring/Summer 2020 print edition of Columbia Magazine with the title "The Morningside Candidate."