By today’s standards, Thomas Mann hardly qualifies as a confessional writer. The great German novelist, who won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1929, never wrote a soul-baring memoir or made himself the main character in a book the way many writers do today. If anything, Mann strikes twenty-first-century readers as practically Olympian, with his dignified public image and formal prose.

But the further you delve into his work and biography, the clearer it becomes that Mann was a daringly personal novelist. As his original readers recognized, his stories are often rooted directly in his own life. Buddenbrooks, the debut novel that made him famous in his twenties, reflects the history of the Mann family so closely that it caused a scandal in his hometown of Lübeck. In Death in Venice he wrote intimately about the homosexual desires concealed behind his public image as a married father of six children. In other books he wrote about his fierce rivalry with his older brother Heinrich, who was also a novelist.

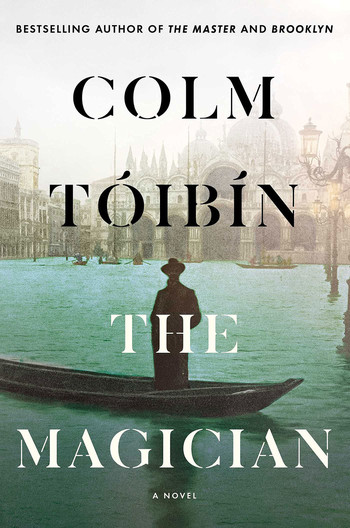

The complicated relationship between Mann’s life and art has made him a favorite subject for biographers and critics. Now Colm Tóibín, Columbia’s Irene and Sidney B. Silverman Professor of the Humanities, brings a novelist’s eye to the subject in The Magician, a fictionalized retelling of Mann’s story. Tóibín’s 2004 novel The Master gave Henry James similar treatment, and the books have been aptly described by one critic as “bionovs,” the literary equivalent of “biopics”—accessible narratives that dramatize key episodes and major themes in the subject’s life. Tóibín’s aim is to decode the experiences so elaborately encoded in Mann’s fiction.

“The Magician” was Mann’s family nickname, bestowed by his children after he dressed up as a wizard for a costume party. Not only did it echo the title of his most famous novel, The Magic Mountain, it also captured the sense that there was something uncanny about his powers — that his imagination masked secrets, possibly dark ones. Tóibín highlights this idea from the first chapter, when we meet young Thomas, the teenage scion of a prominent family of merchants. To all appearances, he was their natural successor. But “when he heard them say that he was the one who would shine in the world of business,” Tóibín writes, “he almost shuddered at the thought that if these people knew who he really was, they would take a different view of him.”

Tóibín traces Mann’s development from failing high-school student to apprentice writer to celebrated man of letters in Munich, where he lived in high style after marrying Katia Pringsheim, the daughter of a wealthy Jewish family that had converted to Protestantism. During World War I, Mann emerged as an influential voice in politics: initially a superpatriot, after Germany’s defeat he evolved into a steadfast defender of democracy and opponent of Nazism. When the Nazis took power in 1933, he went into exile in the US, where he became a living symbol of German culture and freedom.

All along, however, Tóibín suggests that the real Mann was a poet and a dreamer, fascinated by sickness, obsession, and decline. The closest thing to a self-portrait in his fiction is the character of Gustav von Aschenbach in Death in Venice, a disciplined and celebrated writer who literally throws his life away to remain near the teenage boy he has fallen in love with. One of Tóibín’s main purposes in The Magician is to imagine what Mann’s actual erotic life was like, based on hints from his works and diaries. Constrained by his own fame, he was usually content with exchanging meaningful looks with young men he encountered at hotels: “Anyone who follows your eyes can see where they land,” a friend teases him in the novel.

Mann’s secret life threatened disaster when he had to flee Germany, leaving behind diaries in which he had confided his homoerotic feelings and experiences. “The diaries would make clear who he was and what he dreamed about,” Tóibín writes, and the Nazis wouldn’t have hesitated to use them to destroy his reputation. After some close calls, Mann managed to have the diaries spirited out of the country, and they weren’t published until long after his death in 1955. He would be surprised to learn that, in 2021, “who he was and what he dreamed about” are among his chief claims on the attention of posterity, including the new readers who will surely come to his work thanks to Colm Tóibín’s homage.