“History,” Henry Kissinger told Richard Nixon on the eve of the president’s resignation in August 1974, “will treat you more kindly than your contemporaries have.” He has been proven correct. When Nixon died in 1994, his achievements, particularly in foreign policy, dominated the historical assessments of the only U.S. president to have resigned.

The opposite has been the case with Kissinger. Journalists fawned over him when he was in office. In 1973, he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for negotiating the imperfect end to the Vietnam War, even as Nixon was squirming in the purgatory of Watergate. But over time, “Kissinger the war criminal” came to replace the image of a globe-trotting super-diplomat.

Robert Dallek, the best-selling author of a sympathetic biography of John F. Kennedy, uses the Nixon-Kissinger collaboration to retell the story of the opening to China, the end of the Vietnam War, the unfolding of Soviet-American détente, and the Middle East peace process of the 1970s. But is there anything new to learn from a replay of the machinations inside the Nixon White House, when both men have been subjected to intense scrutiny by biographers Stephen Ambrose, Herbert Parmet, Anthony Summers, Seymour Hersh, and Walter Isaacson, among others? As Dallek himself acknowledges at the outset: “We know almost all of what they did during their five and a half years in the White House.”

But Dallek wants to “cast fresh light” on “who they were and how they collaborated in their use and abuse of power.” This fresh light comes in part from volumes of newly released documents and recordings, including transcripts of Kissinger’s telephone conversations that were made available in 2003.

Nixon, for example, is quoted as early as the winter of 1969–70 as accepting that the Vietnam War was unwinnable. Yet, he refused to acknowledge this in public, because “[w]e simply cannot tell the mothers of our casualties in Vietnam that it was all to no purpose.”

What emerges is a disturbing portrait of how personal ambition and a desire for public praise were as important in driving foreign policy as any grand geopolitical analysis. And the policies themselves were often marked by a failure to pay much heed to local and regional circumstances.

Take the opening to China. At one level, it is a story of a visionary president and his brilliant adviser finding a way to break the two-decades-long deadlock in Sino-American relations. With Kissinger’s two trips to Beijing in 1971 and Nixon’s dramatic weeklong sojourn in February 1972, the world was changed, most would maintain, for the better. True statesmanship, no doubt.

But in their quest to secure the opening, Kissinger and Nixon made plenty of mistakes. Most spectacularly, they took the side of Pakistan in that country’s 1970-71 war with India, which resulted in the creation of an independent Bangladesh and a huge public relations defeat for the administration. Viewing this war as a mere extension of Cold War politics, Kissinger and Nixon saw a power struggle between Soviet-supported India and a Chinese-backed Pakistan, a country that had been helpful as a channel between Washington and Beijing. That the crisis was in large part the result of the Pakistani government’s repressive policies in East Pakistan (today’s Bangladesh) was lost as Kissinger told Nixon that “we can’t let a friend of ours and China get screwed in a conflict with a friend of Russia’s.”

Of course, Pakistan did get screwed, losing the eastern half of its territory. Some half a million Bengalis were killed. Moreover, the Chinese saw the Americans as ineffective, and relations with the Soviet Union and India were ill served.

But if the China trip did have a strong upside, the conclusion of the Vietnam War is a different story. The January 1973 settlement that ended America’s direct involvement in the war was in large part a result of Nixon and Kissinger’s willingness to sacrifice Washington’s long-standing South Vietnamese allies. The Paris Peace Accords that Kissinger had negotiated left 200,000 North Vietnamese troops on South Vietnam’s territory, after an enormous bombing campaign failed to subdue Hanoi. Thus, the real target of Nixon and Kissinger’s wrath during the run up to the peace settlement was South Vietnam’s President Nguyen Van Thieu, whom they regularly castigated as “a complete SOB.”

In fact, throughout the negotiations with his North Vietnamese, Chinese, and Soviet counterparts, Kissinger repeatedly indicated that the United States had little long-term interest in an independent South Vietnam. After he had initialed the agreement, he counseled Nixon against publicizing the deal as a “lasting peace or a guaranteed peace.” He further predicted that “this thing is almost certain to blow up sooner or later.” Two years later, at the end of April 1975, Vietnam, which had not seen a day of full peace after the peace agreement that earned Kissinger the Nobel Peace Prize, was unified after a massive North Vietnamese offensive made possible by generous Soviet and Chinese military assistance. What Nixon and Kissinger wanted — and got — was “a decent interval” between the American exit and South Vietnam’s collapse. “The entire policy was a disaster,” Dallek concludes.

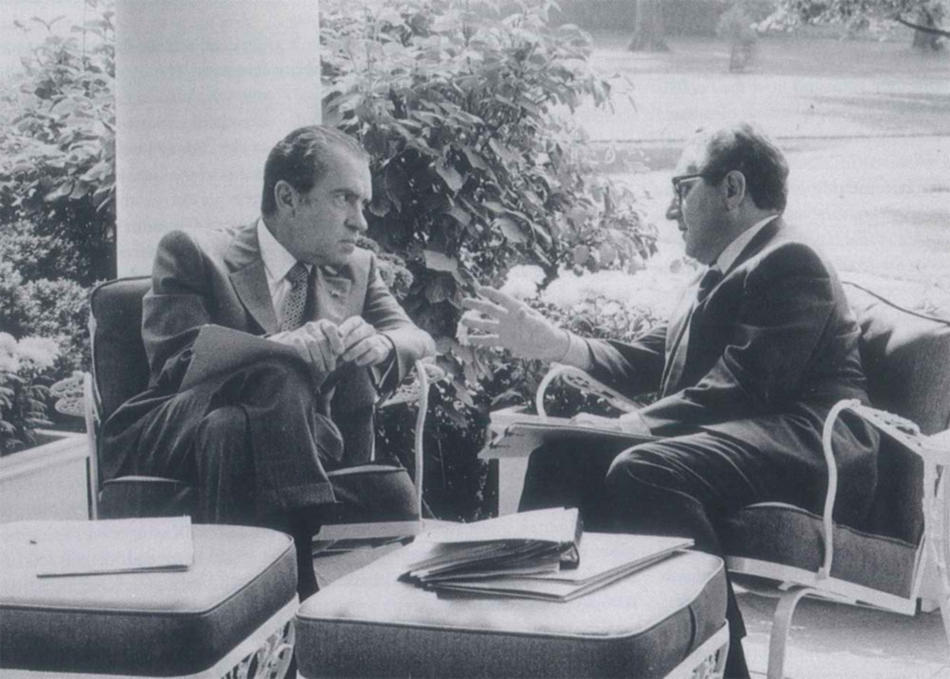

Dallek is at his best in exploring the personal relationship between Nixon and Kissinger. The grocer’s son from California, who made a career as one of the most successful and tragic American politicians of the 20th century, and the Jewish immigrant from Germany, who became the only person to simultaneously hold the offices of national security advisor and secretary of state were, indeed, an unlikely combination. As Dallek points out, Nixon hated academics (particularly from Harvard) and often railed against the “Jewish press” in front of Kissinger.

What allied them during their years in office together was their hunger for power, since both saw in each other the means of gaining it. The result, in Dallek’s words, shows “Nixon deceiving himself, the Congress, the courts, the press, and the public; Kissinger endorsing or acquiescing in many presidential acts of deception and engaging in many of his own.” It also shows Kissinger pandering to Nixon, ignoring his anti-Semitic remarks, and stroking the president’s vulnerable ego to secure his own influence in the administration.

The two men resented each other as well. Nixon wanted to fire Kissinger — in part because he was jealous of his superior relationship with the press — early in his second term. “Watergate made it impossible,” Dallek writes, because Nixon needed “to use Henry and foreign policy to counter threats of impeachment.” By cooperating, Kissinger assured himself of becoming secretary of state, a post he would hang on to after Nixon’s departure in August 1974.

After Nixon flew off on the helicopter from the White House lawn, the two men seldom saw each other. “We never knew each other personally,” Kissinger told an interviewer, with apparent sincerity, in 2003.

Although Dallek calls them “partners in power” and spends much time assessing their “shared traits” (love of secrecy, unparalleled ambition, need for approval, and flexible approach to the truth), Nixon comes across as the greater villain, the man whose obsessions and insecurities were at the root of his administration’s collapse.

Dallek agrees that Kissinger deserved the Nobel Peace Prize — not for ending the Vietnam War, but for his efforts in bringing about a truce in the Middle East after the 1973 October War. These efforts were, Dallek writes, the “greatest achievements of his tenure as national security adviser and secretary of state.”

Yet Kissinger’s involvement in the peace process was also driven by self-interest. Shuttling between the various Middle East capitals was a welcome relief from a Washington consumed by Watergate and provided respite from Nixon’s incessant demands that his underling make it clear to the American public that, without him in office, the world would return to the dangers of the early Cold War. On the policy side, Kissinger’s Middle East program was motivated by a desire to eject the Soviets from the region and to assure America’s role as the major external player there. In this he succeeded. But it was, as subsequent decades have shown, a mixed blessing.

Nixon and Kissinger does not meet the high standard set by Dallek’s previous works on JFK or Lyndon Johnson. While Dallek meets the difficult challenge of breathing new life into an old story, he fails in advancing any significant new argument about the odd couple. Nevertheless, the book is a pleasure to read. Through Dallek, Nixon and Kissinger come to life in a way that few other works have been able to accomplish.

Jussi M. Hanhimäki is professor of international history and politics at the Graduate Institute of International Studies (Geneva, Switzerland) and the author of The Flawed Architect: Henry Kissinger and American Foreign Policy (Oxford University Press, 2004).