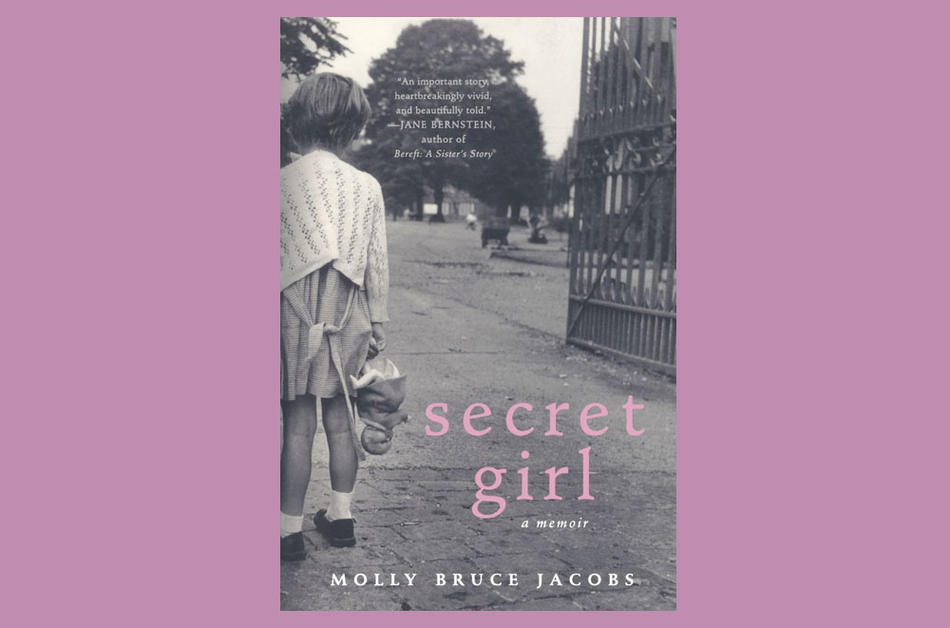

Secret Girl begins with its author and protagonist, Molly Bruce Jacobs ’81LAW, driving into Baltimore on a gray November day in 1992 to meet her sister, Anne. But this is no ordinary sibling reunion:

Anne was thirty-five years old. I was thirty-eight. Though she lived only a half-hour from my house, I’d never seen her before — not even in a photograph. I’d never touched her hand, never heard her voice. I didn’t even know the color of her eyes, but I imagined them to be green like mine. All my life, Anne had been a family secret, and I’d pretended she did not exist.

With this guilty admission, delivered matter-of-factly on page one, Jacobs sets both the scene and tone of her surprisingly measured and moving memoir. The writing could easily have erred toward the maudlin. The story all but begs for an overwrought telling: Jacobs’s younger sister, Anne, a twin, was born with hydrocephalus (“water on the brain”) in 1957, when such babies were routinely shuttered in institutions until they died, usually within a year. Jacobs’s parents did what parents then were advised to do: They sent Anne away, took her twin sister Laura home, and tried to forget the fact of their third child. But Anne defied all prognoses. She didn’t die, her condition stabilized, and by age four, her psychiatric caseworker was describing her as “bright-featured,” “aware,” a girl who “liked attention.” She was, however, profoundly delayed, and as an adult had a mental age equivalent to that of a normal nine-year-old.

It was too much for her parents, who refused to bring her home. Instead, they lobbied for her permanent placement at Rosewood State Hospital, a large mental institution a short drive from the family’s upscale Victorian home. According to her caseworker’s notes, her father questioned her mother’s stability, and both parents worried that they had “developed a style of living that [did] not leave room for Anne.”

Jacobs learns this and more while poring over Anne’s voluminous medical file, in an attempt to piece together her sister’s lost history. Though Jacobs had known of Anne’s existence since the age of 13 — when her father divulged the secret — she finds herself shaken by the details of her sister’s cold and complete abandonment. Jacobs refrains from vilifying her parents, acknowledging, “I can only imagine how badly my mother must have felt.” At the same time, she is baffled by their stated reasons for forsaking their child: “What was it about their ‘style of living,’” she wonders, “that completely precluded Anne?”

Jacobs is keenly aware that she, too, denied her sister. At 15, Jacobs discovers the “magic” of gin, and for the next 23 years she battles alcoholism, even as she graduates from Columbia Law School, works as an attorney, then a writer, marries, and has two sons (she quits drinking during her pregnancies, but quickly resumes). It’s only after she gets sober at 38 that Jacobs suddenly resolves to visit Anne. She announces her intentions to her psychiatrist (surprising herself as much as him) and three days later is en route to her sister, with a mix of excitement and dread. She has no idea what she will find, whether Anne can perform even the simplest of functions — feeding and dressing herself, using the bathroom — on her own. (Anne, as it turns out, operates much like a strong-willed six-year-old, physically capable but cognitively, socially, and emotionally immature.)

Jacobs sees in Anne hidden pieces of herself. She sees the spontaneity and unfiltered emotions that were repressed in her own childhood home, where the “air inside whispered of the civilized restraint and discipline” that her mother believed came “from good breeding and good boarding schools,” and “where human smells were largely absent.” In raw, loud, untamed Anne, Jacobs sees everything she’s tried to suppress in herself, for her parents’ and appearances’ sake. Anne completes her, filling the void she’d long tried to fill with alcohol: “[W]e were linked,” writes Jacobs, “in a way that echoed the ancient Chinese symbol of unity: yin and yang, opposite halves of a circle, mirror images in black and white, each of which contains a dot, a miniature template of its other half.”

Secret Girl is at its best when recounting the sisters’ shared moments (their first Christmas together, when Anne performs a rousing rendition of “Shake Your Booty,” is particularly poignant). A shade less compelling are the fabricated scenes from Anne’s childhood and early adulthood — a device Jacobs relies on intermittently (with fair warning to the reader) throughout the book. Because she can’t know what Anne actually experienced, Jacobs uses what she gleans from Anne’s records to weave the likely narrative of her life, told largely through imagined dialogues among her parents, psychiatrists, social workers, and other caretakers. The technique works well enough for the willing reader, and given the gaps Jacobs had to contend with, hers is a creative and elegant solution.

Still, these manufactured exchanges lack the veracity and emotional depth of Jacobs’s genuine memories. Fortunately, Jacobs’s actual recollections have power enough to carry the whole. If you read this book, read the epilogue, but save it for last, as the author intended. It will leave you reeling. Secret Girl’s final pages are both haunting and horrifying, and it’s here that Jacobs shows her courage and tenacity as a writer and memoirist.