Patrick J. McCloskey’s candid and vividly told book, The Street Stops Here: A Year at a Catholic High School in Harlem, takes us into the no-frills classrooms of Rice High School and shines a bright light onto the world of an all-boys school and urban parochial education. Front and center in McCloskey’s compelling narrative is Orlando Gober, the outspoken first black principal of Rice, who hands incoming freshmen Bic pens stamped with the slogan Believe and Succeed.

For freshman Ricky Rodriguez, a borderline student, donning the Rice sweater represents his best chance to graduate from high school and go on to college. But the transition from a public elementary school to Rice, where discipline is strict and academic standards are high, is difficult. It doesn’t take long for Rodriguez, a testy Dominican, who is frequently baited by other students, to get into trouble.

“‘I can’t deal with this place, man,’” Rodriguez tells Christopher Abbasse, Rice’s ponytailed dean of students. “‘You always on my back, yo. . . . I’m used to being myself at public school. . . . I didn’t have to worry about getting a 70, or rules about behavior and dress code. We have to talk a certain way at Rice. Damn, we have to watch out for the N-word and be on time. There I could show up when I wanted and say whatever. At Rice, there’s demands every minute and I don’t know how to handle them all.’”

After a long talk with Abbasse about Rice rules and philosophy, Rodriguez realizes that if he doesn’t shape up he is going to lose his privately funded voucher, which paid for his Rice tuition. Rodriguez doesn’t want to end up back in public school. He doesn’t want to disappoint his mother, who supports him and his younger sister with the $200 a week she earns as a waitress. With Abbasse’s help, he keeps his temper in check and improves his grades.

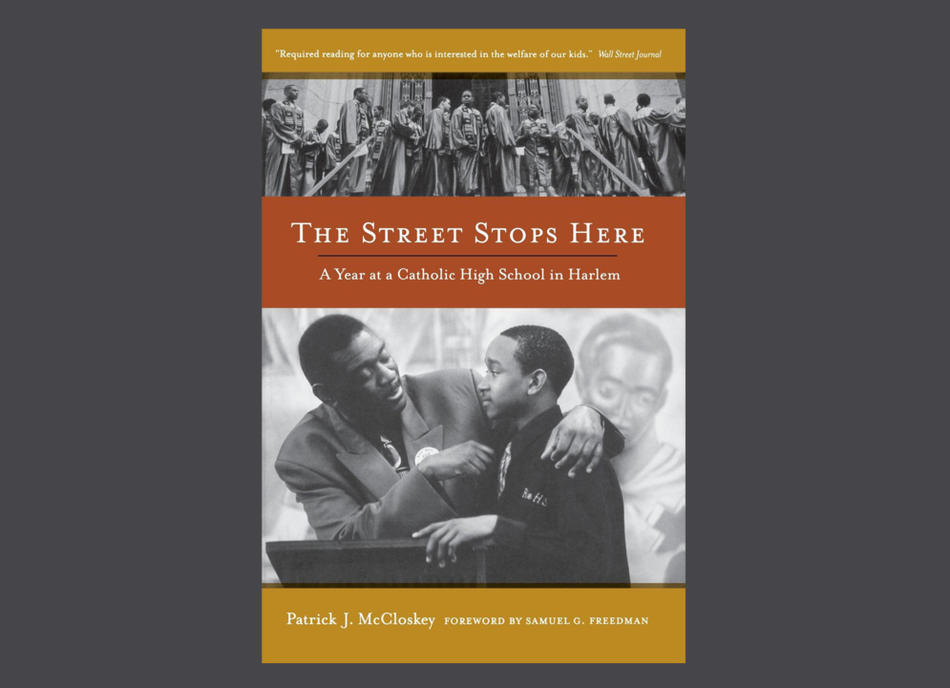

Catholic-school teaching traditionally stresses rules, a core curriculum taught to all students, and the inculcation of moral values. Principal Gober, who converted to Catholicism, frequently booms, “Conform or leave!” at his freshman class. McCloskey credits much of Gober’s success in increasing enrollment and improving academic achievement at Rice to his insistence that street culture, from use of the N-word to the wearing of do-rags, be kept out of the school. Gober also emphasizes the importance of intensive one-on-one counseling, encourages academic achievement (he established 70 as the minimum passing grade), and celebrates good behavior at every opportunity. Most important, Gober is a respected father figure for the many students without male role models at home. We learn that his tenure was a short one: Gober died in 2005 of complications from diabetes.

Parochial schools like Rice have educated generations of Irish, Italian, and other European immigrants. Today, the faculties of Catholic schools are overwhelmingly nonreligious. They serve large African American (often non-Catholic) and Hispanic communities, spend much less per pupil than does the average public school, and graduate more than 70 percent of their urban male students. In many inner-city public schools, McCloskey says, fewer than 40 percent of black and Latino males make it to graduation.

The Street Stops Here is being released at a time when Catholic schools, the only affordable alternative to public schools for many urban families, are being shuttered by the dozen. According to a new study, urban Catholic schools have lost 27 percent of their students since 1989. White flight to the suburbs has emptied the pews and coffers of Catholic urban dioceses. And while the Obama administration has increased federal funding for education, it remains resistant, so far, to government-funded voucher programs (a drain on resources away from public schools, some say), which, McCloskey argues, could help low-income families send their children to parochial schools.

McCloskey, a Canadian-American journalist, knows from personal experience how hard it is for these families to keep their children out of trouble and provide them with a good education. He got the idea for his book in the late 1990s, when, as a single parent with a modest income, he embarked upon the difficult task of finding an academically sound and affordable high school in the New York City area for his daughter. The public schools he tried were inadequate, and the private school in Brooklyn, where he eventually enrolled his daughter, cost $16,000 a year. McCloskey paid the tuition, in part, by waiting tables at a steak house in Brooklyn.

In 1996, he enrolled part-time in Columbia’s Graduate School of Journalism and began to write articles about inner-city schools. Under the tutelage of Samuel G. Freedman, a journalism school professor who teaches a celebrated course in book writing, McCloskey put together the concept for a book on parochial education. It took 12 years for him to report and write The Street Stops Here, for which Freedman wrote the foreword.

During the 1999–2000 school year, McCloskey immersed himself as a journalist-in-residence at Rice. He was given complete access, and his observations are frank. He takes us into the local bar where veteran teachers gather after work and into run-down apartment buildings that some students go home to at the end of the day. But the touchstone of the book is Rice’s mercurial and visionary principal. A former Black Panther and activist, Gober does not always agree with his Catholic administrators and is prone to fits of messianic zeal. Mostly, though, he goads his acolytes to empower themselves and win “the war against the culture of academic failure” and anti-intellectualism that he believed dooms many young urban black men.

Undoubtedly, Gober’s fervor and charisma contributed to the turnaround of students like Ricky Rodriguez. But McCloskey points to the pedagogical method at work at Rice, which the principal pounded into his students and faculty, as the key to the school’s success. Again and again, Gober exhorts his students to take responsibility for their futures, to be disciplined, and to place academic achievement above all else, including even the glory of Rice’s famous basketball team. That may seem old-fashioned compared to the holistic, more creative programs of some charter schools, but virtually all of Rice’s graduates who apply are accepted to colleges, and some even make it into the Ivy League.

Rodriguez, by the way, graduated from Clarkson University in 2007.