Told that her parents are rushing dinner because they’re “going to hear Angela Davis speak at the public library,” Eulabee, the thirteen-year-old narrator of Vendela Vida’s evocative coming-of-age novel We Run the Tides, sighs dramatically and complains:

“Sometimes I feel like I missed out on all the interesting . . .” I am about to say periods but decide on epochs instead. My parents look at me quizzically. I probably didn’t pronounce it right. I move on. “The Velvet Revolution in Czechoslovakia, and even here I missed Angela Davis, the Black Panthers, Patty Hearst.”

Her lament is classic teen and classic Gen X, and Eulabee checks both boxes. It’s 1984, and this bookish, mildly rebellious eighth grader and three of her classmates at the Spragg School for Girls — Julia, Faith, and the cunning and beautiful Maria Fabiola, Eulabee’s BFF since kindergarten — own the streets of their San Francisco neighborhood of Sea Cliff. “We know these wide streets,” Eulabee says, “and how they slope, how they curve toward the shore, and we know their houses.” Eulabee and Maria Fabiola’s most daring exploit, honed over years, is to quickly scale the cliff that separates two beaches by precisely timing the ebb and flow of the tides.

Inevitably this youthful invincibility gives way to the usual adolescent encroachments of sexuality, jealousy, deceit, and betrayal, as well as grimmer intrusions. In the aftermath of a tragedy that occurs during a birthday sleepover, Eulabee’s life begins to unravel. Maria Fabiola hatches a vicious lie about an encounter with a stranger and enlists Julia and Faith as confederates, announcing gleefully, “This is going to be such a big deal.” At school, Eulabee is questioned by two police officers and tells the truth — that nothing happened. The school drops the matter. Within hours, Maria Fabiola has succeeded in turning Eulabee into a schoolwide pariah.

Eulabee has been marooned in this friendless purgatory for a few months when Maria Fabiola vanishes, sending the city into a frenzy (Eulabee is astonished to discover, via the nightly news, that her longtime friend is an heiress and thus a target for kidnappers). Further complications ensue, including two more missing girls and another shocking tragedy. Ultimately, Eulabee is expelled not only from teenage society but from Spragg itself.

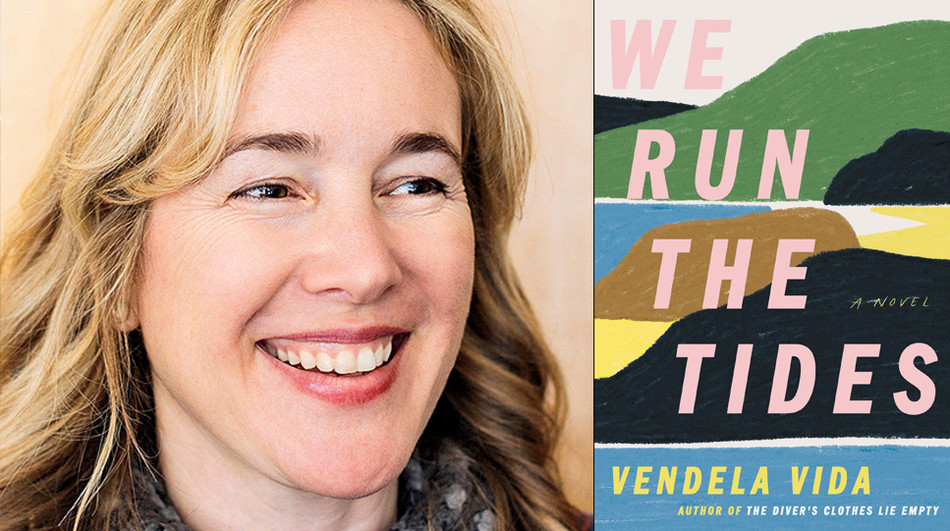

This summary risks giving a misimpression of the novel as bleak; in fact, it is funny and full of quirky, indelible details. Vida ’96SOA, whose four previous novels include The Lovers and The Diver’s Clothes Lie Empty, creates a finely etched portrait of both a generation and a city that seem lost in a gray zone between two more consequential eras. As Eulabee notes, the girls were born too late to experience San Francisco’s radical heyday or its legendary Summer of Love. And the Bay Area’s high-tech revolution, which would ultimately bring the kazillionaire class to Sea Cliff, had hardly begun. In such an indeterminate era, it’s no wonder Maria Fabiola concludes that “the only way out was to be extraordinary.”

Like Odysseus, whose story the novel invokes, the adult Eulabee wanders far from home but eventually returns to a much-changed San Francisco in her forties, husband and infant son in tow. In a coda-like final chapter set in 2019, Eulabee, now a professional translator, re-encounters Maria Fabiola while attending a conference on Capri, near the very spot where Odysseus lashes himself to his ship’s mast to avoid the pull of the Sirens’ deadly song. Maria Fabiola has been incommunicado for thirty-plus years, but her power to bewitch every male in the vicinity, as well as her skill at spinning whoppers, remain stunningly intact. As Eulabee is leaving the island, the Sirens sing out to her, too — in the form of a cell phone ringing ever more loudly within her bag — but they can’t suck her in. A far more powerful call is beckoning her home.