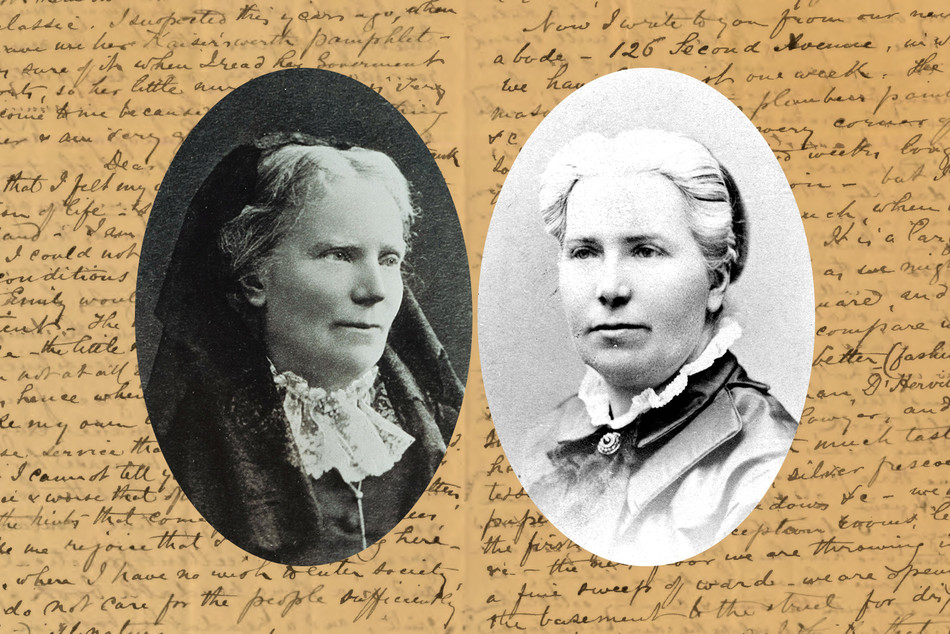

History is filled with pioneering figures who, on closer inspection, are found to be seriously flawed. In The Doctors Blackwell: How Two Pioneering Sisters Brought Medicine to Women — and Women to Medicine, a new biography by Janice P. Nimura ’01GSAS, Elizabeth Blackwell — the first woman to receive a medical degree in the United States — and her younger sister Emily, also a physician, have their feminist legacies slightly tarnished. But trading hagiography for historical fact is always a worthwhile enterprise, and Nimura’s impressively researched book, which makes liberal use of the subjects’ letters and journals, renders these nineteenth-century groundbreakers as complex, contradictory human beings.

Nimura, who has a master’s in East Asian studies from Columbia, is known for her skill at archival treasure-hunting. Like The Doctors Blackwell, her first book, Daughters of the Samurai, was a joint biography of women who were extraordinary for their time — in that case, young Japanese girls who were sent to the United States in the late 1800s to learn Western culture and bring that knowledge back to their home country.

The Blackwell sisters were extraordinary for different but no less compelling reasons. Born in 1821 and raised in a family of nine children by abolitionist parents, Elizabeth Blackwell was determined to attend medical school. This was a strange choice for a woman who wrote, “The very thought of dwelling on the physical structure of the body and its various ailments filled me with disgust.” Nimura points out that becoming a physician was mainly a means to an end for Elizabeth — a way to make a name for herself and demonstrate that women could be the intellectual equals of men. She never seemed particularly interested in curing disease or easing people’s suffering.

One part of the Blackwell story that’s well established is that Elizabeth was rejected from twenty-nine medical schools before she was accepted, in 1847, to Geneva Medical College in upstate New York (Columbia did not admit its first female medical students until seventy years later). Nimura fleshes out this oft-cited description of Blackwell’s struggle to get into med school with a story about how the acceptance nearly didn’t happen. Faculty at Geneva opted to let their students decide whether to admit her, assuming that the young men would reject the idea of a woman classmate. Instead, students found the possibility amusing and voted unanimously to let Elizabeth enroll.

Emily Blackwell, five years younger than Elizabeth, followed her sister’s career path after navigating the same medical-school admissions roadblocks. She became only the third woman in the United States to earn a medical degree.

One challenge the sisters didn’t anticipate: that after overcoming so many obstacles to obtain their degrees, they’d face just as many to practicing medicine. The public wasn’t ready to trust its health to female physicians. But one sector of the population couldn’t afford to be choosy. Poor people were just grateful to receive care. Thus Elizabeth and Emily opened the New York Infirmary for Indigent Women and Children on May 12, 1857.

Nimura makes it clear that Elizabeth — in spite of her social reticence and dim view of most other people — makes shrewd choices in the women and men she recruits to help raise funds for the infirmary. Her fame brings her in contact with many prominent figures of the time, and the narrative is peppered with recognizable names like Florence Nightingale, Lady Byron, George Eliot, and Henry Ward Beecher (Harriet Beecher Stowe’s brother). In Washington, DC, as a tourist during the Civil War, Elizabeth even meets President Abraham Lincoln 1861HON, but is unimpressed. Despite her abolitionist sympathies, she didn’t approve of either side in the conflict.

When it comes to Elizabeth’s legacy as a Victorian feminist, Nimura doesn’t gloss over her subject’s contradictory views. Elizabeth didn’t support the contemporary women’s rights movements and believed that most women were not well-educated enough to have a political voice. She was anti-contraception and anti-vaccine. She was also horrified by the idea of abortion, deeming it a “gross perversion and destruction of motherhood.” (For readers wanting more of Blackwell’s voice and opinions, the Columbia Rare Book and Manuscript Library contains a series of her letters to her close friend Barbara Bodichon, including one in which she criticizes Florence Nightingale’s book on nursing as ill-tempered, dogmatic, and exaggerated!)

Nimura ends her book with numbers: when the sisters died, within months of each other in 1910, there were more than nine thousand women doctors in the United States, making up about 6 percent of all physicians. Today slightly over a third of all doctors — and over half of medical students — are female. Elizabeth and Emily Blackwell, reluctant feminists, are the matriarchs of them all.