In April 1953, the month Judy Garland recorded his song “Heartbroken,” Phil Springer ’50CC, a twenty-seven-year-old composer on the Upper East Side, phoned a lyricist whose work he admired. Her name was Joan Javits, and she was a staff writer in the Brill Building, the eleven-story song factory at Broadway and 49th where writers, publishers, producers, and performers churned out material in pursuit of the golden apple — a hit record.

Javits had penned the words to “Second Fling,” a plucky ditty sung by country crooner Eddy Arnold and released earlier that year. It wasn’t a hit, but it had sassy lines like The ladies used to like my lovin’ / And I ain’t forgot a thing / I got some oats need sowin’, out I’m goin’ / Have me a second fling.

Springer had already worked with some of the best lyricists around. He’d written “Heartbroken” with Fred Ebb, who with John Kander ’54GSAS would go on to create the musicals Cabaret and Chicago. And his 1950 song “Teasin,’” sung by Connie Haines, had lyrics by Richard Adler, later known for The Pajama Game and Damn Yankees. A sly sendup of coquetry, “Teasin’” had reached no. 4 on the charts — a bona fide hit. Now Springer sought to join forces with Javits.

“I called her and said, ‘I would like to write songs with you,’” says Springer, in a rich New Yorkese cured with the salt of old Broadway. “She said, ‘I don’t have time to write with you.’ I said, ‘Do you know my song ‘Teasin’’?’ She said, ‘Of course. It was a hit.’ I said, ‘Did you ever write a hit?’ She said, ‘No.’ I said, ‘You’re gonna tell me that a songwriter who never had a hit is refusing to work with a songwriter who had a hit?’ She said, ‘What are you doing tonight?’ I said, ‘I’m writing with you.’ And that’s how we started.”

So in the spring of 1953, with former Columbia president Dwight D. Eisenhower ’47HON in the White House and the radio in every Studebaker on the parkway yipping with “(How Much Is) That Doggie in the Window,” Springer and Javits set out for Hit City.

A few months later, the bosses at RCA Victor told Javits and Springer that they wanted a Christmas number for Eartha Kitt, a sultry twenty-six-year-old entertainer who had sizzled in a sleeveless mini-dress in the Broadway revue New Faces of 1952, and whose recording of the French song “C’est si bon” was riding the charts. Springer was baffled. Christmas songs meant sleigh bells, Yule logs, and a plump, chaste, white-bearded man in a red suit, and Kitt, who would call her memoir Confessions of a Sex Kitten, was not to be confused with Bing Crosby. When Springer raised his concerns, the bosses told him, “Just worry about the music.”

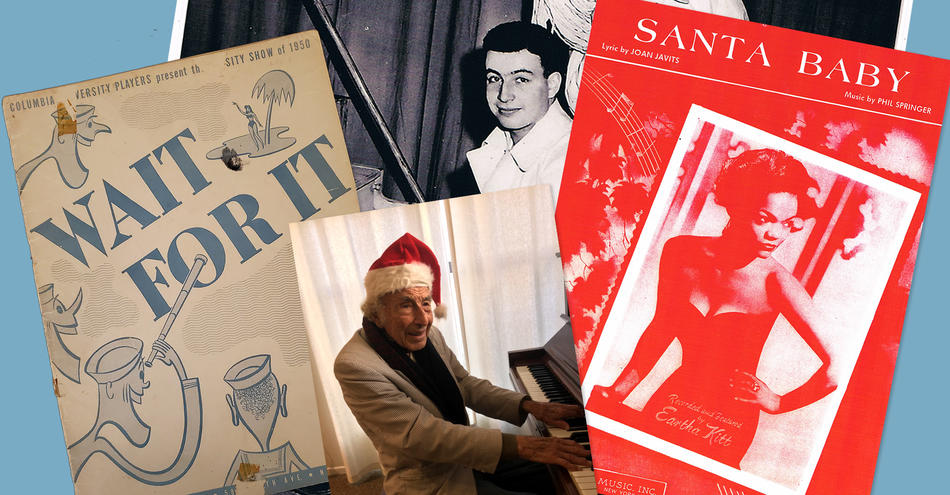

So Springer did, but he didn’t have to worry too much. “People ask me what comes first in songwriting, the music or the lyrics,” he says, “and the answer is neither: the title comes first.” And Javits delivered a beauty: “Santa Baby.” It clicked. Springer came up with four perfect notes to match the syllables. “Once you find a title, you then write a little tune, or the lyric writer writes a line, and you work on the song together.” Using a standard chord progression, Springer crafted a catchy melody within Kitt’s vocal range. “I took the song directly to RCA Victor and played it for the musical director, Henri René, and he made that great arrangement that you hear when Eartha Kitt sings,” says Springer. “I wish he was still alive, because I’d send him a big check.”

Released on October 6, 1953, “Santa Baby” cast Kitt as a coy, go-getting sweetheart who addresses a certain “Santa” on intimate terms, saying she’s been “an awful good girl” and would like to collect her Christmas reward: a Cadillac convertible (light blue), a yacht, Tiffany ornaments for her Christmas tree, and — she forgot to mention — “one little thing / a ring / I don’t mean on the phone.” In a year when Americans flocked to see Marilyn Monroe in How to Marry a Millionaire, “Santa Baby” caught the zeitgeist.

“That song,” says Springer, “changed my life.”

Springer grew up in Lawrence, Long Island, one of the Five Towns. He took piano lessons and fell in love with the songs on the radio — the top-shelf stuff by Cole Porter, Richard Rodgers 1923CC, 1954HON, the Gershwins, and his favorite, Harold Arlen. At fifteen he began writing songs. He performed one of them in high school, and the kids went so crazy for it that one of them, Marty Mills, offered to introduce Springer to his father, a Brill Building executive who had published “Stardust” in 1929. “And that’s how I met Jack Mills, the greatest independent music publisher in America,” Springer says. “He didn’t take my song, but he encouraged me. He said, ‘When you get out of the army, come back and see me. I think you’ve got talent.’”

Springer was drafted in October 1944 and sent to England and Germany as a jeep driver, and when the officers found out that he could play all the popular songs on piano, they took him off guard duty. “They said, ‘Springer, we’ll do the guarding. You just play the piano.’” One soldier took particular notice of Springer’s facility — it was Mickey Rooney, one of the biggest stars in the world. “When he heard me, he said, ‘Springer, how would you like to be my musical director?’ So I became very friendly with Mickey, and he got me out of my outfit to be his musical director for his army show. He was just a soldier, but naturally everyone treated him like a star.” Springer, too, had special status. “In the army I was protected by officers who just wanted me to do music. Not many guys could play every hit song from America.”

The war ended, and Springer started college at Hofstra before transferring to Columbia, the alma mater of his father, Mordecai Springer 1911CC, 1913LAW. His roommate in John Jay Hall was Arthur Ochs Sulzberger Sr. ’51CC, ’92HON, future publisher of the New York Times, and he studied composition with the conductor and electronic-music pioneer Otto Luening ’81HON. “Luening resented my going down to Broadway and successfully becoming a songwriter,” Springer says, “so he gave me the only C that I ever got.”

Among Springer’s friends was piano wunderkind Dick Hyman ’48CC, composer of the 1947 Varsity Show, and the two would play dual pianos. Springer cowrote the music for the 1948 Varsity Show, Streets of New York, and was the lead composer of the 1950 show, Wait for It, which he considers his first real professional experience. “It was such a great cast and such a wonderful director,” he says. “Broadway-level.” Springer’s songs were so accomplished that BMI published them — only the second Varsity Show score to be published. The other was 1918’s Ten for Five, with music by Richard Rodgers. “Going to Columbia,” Springer says, “was the most beautiful thing that ever happened to me.”

Springer graduated in 1950, and with his new song “Teasin’” on the charts, he went looking for his next hit record. He never imagined that it would be a Christmas song, much less a holiday classic. “Santa Baby” was hardly his magnum opus, but a hit was a hit, and one of the Brill Building’s biggest publishers, Joy Music, allowed Springer to fulfill the dream of any young songwriter by hiring him on staff.

Then, in March 1956, a meteor struck. Just as Capitol Records released Frank Sinatra’s Songs for Swingin’ Lovers!, RCA Victor came out with an album by a ducktailed twenty-one-year-old singer titled Elvis Presley. Ol’ Blue Eyes gave way to “Blue Suede Shoes.” Rock-and-roll, doo-wop and R&B became hot, and the Brill Building saw a new generation of writers: Carole King, Neil Sedaka, Neil Diamond, Laura Nyro, Phil Spector. “The rock revolution put almost all the old-time songwriters out of business,” says Springer. “The Brill Building was taken over by nineteen-year-old kids, rock-and-roll writers and publishers. It was a sad time for most songwriters.”

But not for Springer. Though he was already thirty in 1956, his musical training at Columbia, and later at NYU, allowed him to flourish. “I was so well educated musically that I was able to adapt,” he says. “That was very rare.”

In fact, Springer explicitly straddled the divide. In 1956 he wrote a Top 40 song for Sinatra called “(How Little It Matters) How Little We Know,” with lyrics by Carolyn Leigh (“Witchcraft,” “The Best Is Yet to Come,” “Young at Heart”), and in 1963, Elvis recorded Springer’s “Never Ending.” In between, Springer wrote “The Next Time” for Cliff Richard (“the Elvis of England,” Springer notes), which was featured in the 1963 movie Summer Holiday. In another mode, he composed gems for Dee Dee Warwick (“We’ve Got Everything Going For Us”), Dusty Springfield (“All Cried Out”), and Aretha Franklin (“Her Little Heart Went to Loveland”).

“The 1960s were very productive for me,” Springer says. The decade was less kind, however, to the Brill Building: the British Invasion, led by the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, and other bands that wrote their own songs, spelled doom for the factory system. “When all the songwriters were out of business except for a few of us,” says Springer, “my musicianship allowed me to become a composer for TV shows and movies.”

Springer’s crowning collaboration came in the 1970s, when he teamed up with the man he considers to be the greatest lyricist of the twentieth century: E.Y. “Yip” Harburg (“Over the Rainbow,” “It’s Only a Paper Moon”), best known for The Wizard of Oz. Springer and Harburg worked together for nine years until Harburg’s death in 1981.

Yet of all the songs of Springer’s seventy-plus-year career, none has had the legs of “Santa Baby.” Long a flirty Christmas-party staple — Mae West covered it in 1966 — the song got fresh life when Madonna, going full material girl, recorded a Betty-Boop-inflected rendition in 1987. This heralded a cascade of Santa Babies by the likes of Macy Gray, LeAnn Rimes, Kylie Minogue, Taylor Swift, Ariana Grande, Michael Bublé, and Gwen Stefani.

For Eartha Kitt, the trailblazing diva from the cotton fields of South Carolina who became, in the words of Orson Welles, “the most exciting woman alive,” “Santa Baby” was her biggest hit. She died at age eighty-one in 2008, on Christmas Day.

Springer, now ninety-four, lives in Pacific Palisades on the Westside of Los Angeles. He’s still writing. “I just finished a song called ‘When New York Becomes New York Again,’ which I think has great potential.” He even got a taste of Internet stardom in October, when a video of him playing Beethoven’s Moonlight Sonata went viral, racking up millions of views. “Isn’t that crazy? I never thought I’d become known for playing Beethoven.”

Or, come to that, for writing a Christmas chestnut that’s just a tad more naughty than nice. Decades after the birth of “Santa Baby,” Springer, who owns the rights to it, is still swamped with licensing requests, and the song’s numerous versions have sold millions worldwide. Throw in movie and TV soundtracks (Driving Miss Daisy, The Sopranos) and the sales of ringtones, and the deed to “Santa Baby” would fit well on the Christmas list the song describes, alongside the yacht and the light-blue convertible: for if there’s a gift that keeps on giving, it’s a hit record.