The date, the blind date, my mother’s latest attempt to address what she saw as the longstanding problem of my bachelorhood, had ended cordially, without dessert, and I found myself walking alone through the electrified chaos of Times Square, down to 42nd Street and west, past the bus station and toward the calm beyond 9th Avenue. Near the corner of 11th Avenue, I came upon the Signature Theatre, whose marquee read: Angels in America: A Gay Fantasia on National Themes.

The play had been a hit on Broadway in the early 1990s, I recalled. I hadn’t seen it then, nor had I seen the 2003 film version that Mike Nichols directed for HBO. I knew only that it had something to do with AIDS, and if you had asked me who wrote it, I’d have probably said, “Larry Kramer, or no, Tony Kushner,” or vice versa, since the two names had melded together long ago in my Swiss-cheese consciousness to form a vague idea of a gay Jewish left-wing activist playwright with glasses. But the playbill outside the Signature clearly said Tony Kushner, and it was Kushner, I knew, who had gone to Columbia.

Curious, I stepped into the warmth of the box office, which was open because a show was in progress. The man at the ticket booth said that the Signature Theatre’s production of Angels was one of three Kushner works being featured in the company’s 2010–2011 all-Kushner season (the Signature focuses on one playwright per year), and that Kushner’s latest play, The Intelligent Homosexual’s Guide to Capitalism and Socialism with a Key to the Scriptures, would have its New York debut this spring at the Public Theater, in a coproduction with the Signature.

“I usually don’t buy tickets in advance, since you never know what will happen,” I said, “but maybe I’ll squeeze in a matinee this week.”

The man smiled. “Angels is nearly seven hours long,” he said, and seeing my alarm, he added, “It’s in two parts, Millennium Approaches and Perestroika.” That didn’t help from a commitment standpoint. Yet seven hours did have a kind of thrilling defiance in it, a gothic grandeur, something formidable, even religious. Besides, it was called Angels in America, which didn’t sound boring, with those two capital A’s like spires on a gate through which I would pass. Then he told me that Millennium Approaches and Perestroika each won the Tony Award for Best Play (in 1993 and 1994, respectively), and that Millennium Approaches earned Kushner the 1993 Pulitzer Prize for Drama.

“Sold,” I said, eager to fill this hole in my awareness.

The following Wednesday, I arrived to a packed house and took my seat.

From its incantatory opening — a eulogy given by an Orthodox rabbi for an old immigrant woman he didn’t know — the Signature’s production, directed by Michael Greif, gave me a vision of the thunderbolt that had split the American stage 20 years before. In the fall of 1992, when Angels opened at the Mark Taper Forum in Los Angeles, the New York Times theater critic Frank Rich articulated the wild excitement that had broken out in the theater world over the arrival of what appeared to be the Thing Itself: “Some visionary playwrights want to change the world. Some want to revolutionize the theater. Tony Kushner, the remarkably gifted 36-year-old author of Angels in America, is that rarity of rarities: a writer who has the promise to do both.” The following spring, the play, directed by George C. Wolfe, came to New York with so much hype on its wings that it could hardly be expected to fly so high.

On May 4, 1993, Angels made its Broadway debut at the Walter Kerr Theater. Frank Rich saw the play again and doubled down. “Angels in America speaks so powerfully,” he wrote, “because something far larger and more urgent than the future of the theater is at stake. It really is history that Mr. Kushner intends to crack open.”

Now, in the smaller, more intimate setting of the Signature, Angels spread itself out, revealing the relationships of two conflicted couples in New York, one gay (Louis and Prior), the other Mormon and married (Joe and Harper Pitt), whose lives intersect during the Reagan-fueled mid-1980s, when a culture of individual self-interest arose alongside a deadly epidemic that was attacking marginalized communities. Prior has been diagnosed with AIDS, prompting Louis to a morally perilous decision; the Pitts are ripped apart by Joe’s repressed homosexuality and dawning liberation; and a turbulent angel crashes through Prior’s hospital-room ceiling to deliver burning messages to the feverish, lesion-spotted man.

As we reach the tower of this cathedral of a play, Prior, having battled with the angel and the disease, stands near the Bethesda Fountain in Central Park. It is 1990, and Prior is, by some grace, still alive. “We won’t die secret deaths anymore,” he tells us. “The world only spins forward. We will be citizens. The time has come.”

The universality of Prior’s message, with its faith in the inevitability of progress, was powerful and present and did not need to be named. Yet for all its loaded content, Angels was no polemic, but a furious, head-spinning dialectic, a rapturous, raging, overstuffed, flamboyantly literate, hilarious, horrifying, always-riveting conversation about love, loss, history, survival, and the politics of responsibility. Kushner’s immense human feeling, a cosmic empathy that he extends to all his characters, aroused terror and pity, while the play’s overt theatricality reminded spectators that they were watching a performance, just as Bertolt Brecht, that famous skeptic of naturalism, prescribed, lest the audience dissolve into emotional catharsis and lose its critical eye. Even Angels’ livid dragon, Roy Cohn, a coarse, closeted lawyer and avatar of egotism (based on the historical Roy Cohn, who as a young attorney helped send the Rosenbergs to the electric chair and acted as Senator Joseph McCarthy’s chief counsel during the Army-McCarthy hearings), maintains a certain dignity of ideological and psychological constancy as he dies of AIDS in a hospital bed, haunted by the ghost of Ethel Rosenberg, and huffing forks of fire till the end.

Angels made Kushner famous, and he began engaging his broadening audience wherever and whenever he could — on Charlie Rose, in magazines and books, at talks at universities and synagogues — in an ongoing conversation about politics, art, psychology, sexuality, and intellectual history, with an emphasis on social justice and liberation. “I believe that the playwright should be a kind of public intellectual, even if only a crackpot public intellectual,” Kushner has written. “Someone who asks her or his thoughts to get up before crowds, on platforms, and entertain, challenge, instruct, annoy, provoke, appall.” Kushner has fulfilled this ideal, providing a penetrating, outspoken, erudite, and at times priestly progressive voice, while risking, with every appearance, with every foreword and afterword, with every inspired speech frantically scribbled in the backseat en route to a college commencement, the order of his writing mind and his finite fund of hours.

In a way, Kushner’s whole life is a piece of writing, the words weaving through shifting modes of presentation, entwined in a continuing dialogue, thesis and antithesis unloosening flumes and plumes of new ideas, a waterfall of confessions, expressions, obsessions, impressions, digressions, whole therapy sessions — one learns quickly that there is very little to say about Kushner that he can’t say better himself.

Still, I wanted to speak with him. I sent out queries and was granted an interview on the morning of February 14, which was a free day for me. My purpose was clear-cut: to find out what role a Columbia education might have played in shaping the vision of a great playwright.

The night before the meeting, my mother called. “So what’s new?” she said.

“I’ve been busy,” I told her. “I’m interviewing a playwright tomorrow.”

“Oh? Who?”

“His name is Tony Kushner.”

“Is he married?” My mother gave a light laugh. She had lost her husband six years earlier, and was on the lookout.

“Yes, he’s married,” I said, and took some pleasure in the details. “To a man. Legally. They got married in Massachusetts in 2008. Progress and hope for the world.”

“That’s because they’ve got Barney Frank up there.” My mother said this without judgment, just putting two and two together. “So when are you going to get married?”

I sighed. “We’ve been through this. I have to figure out what kind of life I want, what kind of compromises I can make. I’m . . . you know, I’m . . .”

“You’re what?”

“I’m ambivalent. I’m divided. My head, my heart. I’m torn. There is a battle within, Mom. A bloody civil war.”

“Then settle it already. No one’s getting any younger.”

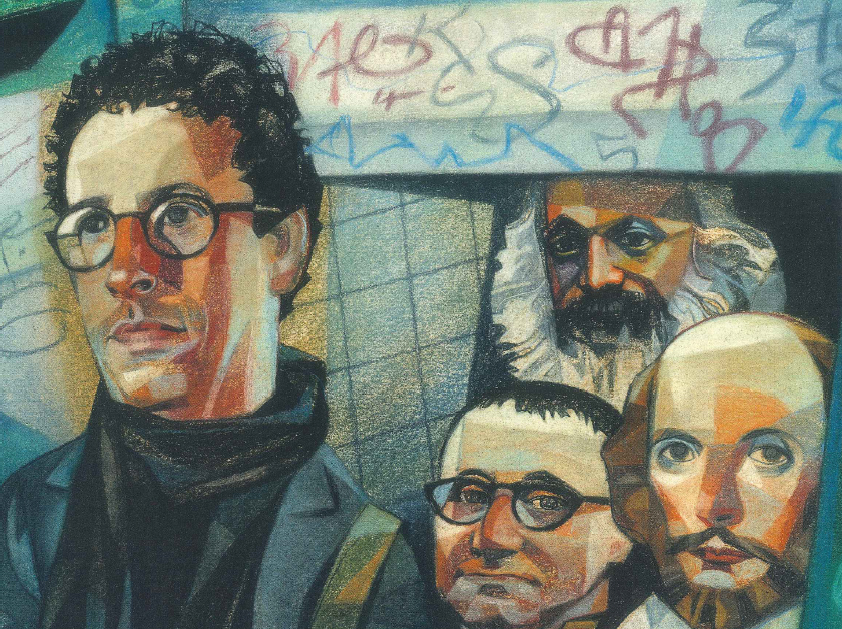

Kushner arrived at 8:05 a.m. at the appointed spot, a café on the Upper West Side. I was waiting at a back table and signaled to him. He wore a stuffed knapsack, round glasses, and a dark half-zip Columbia (the sportswear brand, not the school) fleece pullover. We said hello, shook hands, and sat. I told him how knocked out I was by Angels. He nodded and thanked me. He seemed a little distracted. He ordered oatmeal, with the fruit and nuts on the side, and a cup of decaf. I ordered a slice of whole-grain toast and an espresso. Kushner said that he had just been doing rewrites on his new play, which was in rehearsals. I felt guilty for pulling him away from what sounded like pretty urgent business, but I figured he knew what he was doing.

To get the ball rolling, I said, “So I read that you’ve been writing a screenplay about Lincoln.”

Kushner averted his eyes. “Well, I can’t talk about it a whole lot because we’re going to start filming in the fall of this year —”

“Oh, no, not that,” I said, worried that he thought I was looking for gossip (“Is Daniel Day-Lewis tall enough?”). “I mean, how, uh, has Lincoln emerged for you as a character?”

Kushner nodded once; his needle steadied.

“Steven Spielberg did this film that I wrote for him, Munich, and we both had a very good time doing it, and he asked me to consider this Lincoln project,” Kushner said. “At first I said no, because I found the prospect of writing about somebody as great as Lincoln daunting. As a person he’s an incredibly fascinating study. His psyche is so available to us because of the things he wrote and said. He was a president who wrote and talked about emotion in his public utterances, and more in his letters. The hard thing is that Abraham Lincoln was a genius — I use that word very, very seldom — but I think that he was really one of the upper-echelon geniuses, like Shakespeare or Mozart or Michelangelo. It’s very difficult to write about people like that. Although you can describe the parts of them that seem approachable in terms of how their personalities developed — in Lincoln’s case, his mother died and his sister died when he was very young — what has to remain a mystery is how they did the thing that we most value them for.”

Kushner has a Mahlerian profile, with the glasses and thick hair and forehead, but his face and voice more resemble the actor John Turturro. His manner is warm and relaxed, utterly social, and modest in proportion to his reverence for the artists and thinkers, dead and alive, with whom he communes.

“I think the case could be made that Lincoln is the greatest leader of a democratic country the world has ever known,” said Kushner. “When you look at the horrifying circumstances that he inherited when he became president, and the way that he not only managed to keep the country together but created from the chaos of the beginnings of the war something that eventually became a revolutionary event that overturned institutionalized slavery — in a sense he saved the idea of democracy, made it possible. This is what he says in the Gettysburg Address: that given that the 1848 revolutions in Europe were fairly recent events, the jury was still out on whether or not democracy could work or whether it would simply degenerate into anarchy. The Civil War was, as he says, a great trial of that idea, and he identified slavery as the source of the threat of disintegration of the Union, and saw the way in which slavery and democracy are absolutely antithetical to one another.”

Our food arrived. As Kushner stirred his oatmeal, I thought back on what he said about the limits of biography, and how the principle might apply to Kushner himself. We know, for instance, that he was born in New York City in 1956 and grew up in a small Jewish community in the small southern city of Lake Charles, Louisiana; that he was aware of being gay at the age of six, and that he wrestled with shame and self-hatred and alienation into adulthood; that his father, Bill, a Juilliard-trained clarinetist and poetry lover, had moved the family to Lake Charles to run the family lumber business, and paid his three kids (two boys and a girl) a dollar for every poem they memorized; that Sylvia, Kushner’s mother, had been, at 18, first bassoonist in the orchestra of the New York City Opera, and later played Linda Loman in a Lake Charles Little Theater production of Death of a Salesman that put an arrow in young Tony’s heart; that his parents were New Deal liberals who encouraged Kushner to embrace that which made him different (they meant his Jewishness); that he tried psychotherapy while at Columbia in hopes of changing his sexual preference; that in 1981 he came out to his mother, who was heartbroken at first, but soon came around; that Sylvia died of lung cancer in 1990; and that Bill continued to have trouble accepting his son’s identity until the praise for Angels helped open his mind.

We know these things, and much more.

And yet.

“Were you a history major?” I said, taking a stab.

“Medieval studies.”

“Medieval studies?” I saw stone towers, horses, flashing swords. “How did that come about?”

“I took a freshman expository writing class, and everybody was taught by a graduate student doing some sort of fellowship. The woman that I had was a medievalist who specialized in Anglo-Saxon literature. This was the first time I’d been in the room with a literary scholar, and I was reading Beowulf and The Song of Roland and Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. I had never realized what literature could do, how rigorous you could be about breaking it down and discovering extremely sophisticated aesthetic and philosophical machinery at work, and how the form and the content related, and how this poem, Gawain, which you could read as this fun spook story, is actually about art, about the power of the imagination, about artifice. That was a great revelation to me.

“Midway through my junior or senior year, I went to Karl-Ludwig Selig, the big Don Quixote specialist, and told him I wanted to take Edward Tayler’s two-semester Shakespeare class. A friend of mine had taken the class and said I had to do it. And Selig said, ‘You need to take Latin if you’re going to be a medievalist, and Shakespeare isn’t medieval, so we think you shouldn’t do that.’ So I switched to English.

“In my senior year I took Kenneth Koch’s 20th-century poetry class, which changed my life. He was a wonderful, wonderful teacher. After reading and talking about a poet, he had us write imitations of that poet. I had such awe for the poems and for how difficult poetry was to write. I’m not a poet, but I would write imitations for the requirement, and Koch would give me A’s and A-pluses. I was intimidated by him, so I never tried to become friendly with him, and he didn’t particularly encourage that, or maybe he had some students he seemed to like a lot and I wasn’t one of them. But a couple of times he liked some image and underlined it and wrote ‘good’ on the side. And at that point I wanted to be a playwright, to be a writer. And I kept thinking. ‘Either he’s made a mistake, or is it possible that he thinks I have talent?’ It was very hard for me at that point to —”

Kushner searched for the words, his eyes lowered, and we both said, “accept that.” For a second I thought I was watching Kushner accept it anew.

“But Tayler’s Shakespeare class,” Kushner said. “Nothing I’ve ever done in my life on an intellectual level was as exciting as that.”

Edward Tayler began teaching Literature Humanities in 1960. When he received the Presidential Award for Outstanding Teaching in 1996, the citation noted, “Your students call you magical, learned and passionate, tough yet tender, witty, humane, wholly unique. Many report that you have changed their lives.”

“Tayler’s approach to Shakespeare was dialectical,” Kushner explained. “He said that to read Shakespeare, you only have to be able to count to two. As he saw it, Shakespeare is organized along polarities, and if you could identify the polarities you could start to understand the central dynamic principle of Shakespeare’s plays. I think there’s a great deal of truth in that.”

In my notebook I wrote the number two. I recalled the concluding words of “With a Little Help from My Friends,” Kushner’s post-Angels essay on the myth of the isolated artist and the truth of collaboration. “Marx was right: the smallest indivisible human unit is two people, not one; one is a fiction.”

“I also took a really good class in 20th-century drama with Matthew Wikander,” said Kushner. “That’s where I first read Brecht.”

Brecht. Kushner’s maestro, his model of the political artist, who proposed a socially engaged theater that edified as it entertained.

“Around that time, Joe Papp brought Richard Foreman from his loft to Lincoln Center to do a new version of The Threepenny Opera, which had only been done in the U.S. in Marc Blitzstein’s version in the ’50s. It’s a bowdlerized Threepenny, all the dirty words are taken out, its ugly, scabrous spirit has been removed. It’s still a huge hit because the music is so sublime, but listening to that version you didn’t really get what Brecht was doing; it just seemed sort of quaint. Papp used the very good, very direct Manheim translation of Threepenny, and Richard Foreman, who’s an amazing artist, was the perfect person to do it, and it was one of the greatest things I’ve ever seen.

“Dialectics is the heart of Marxism, and it’s also very much the heart of Brecht. I’ve said this before, but Brecht taught me about Shakespeare, Shakespeare taught me about Brecht, Marx taught me about Shakespeare, and Brecht taught me about Marx.”

Outside the classroom, Kushner, the future political playwright, was gaining an education in activism, having been initially drawn to Columbia out of nostalgia for what he calls the “days of rage” of the 1960s. When Kushner came to Columbia in 1974, the city was on the edge of bankruptcy, and the Morningside Heights branch of the New York Public Library was set to be closed.

“So these old lefties in Morningside Heights went into the library at 113th Street and said, ‘We’re not leaving,’” Kushner recalled. “Word got out. I saw on the bulletin board in Carman Hall that they were having a sit-in. So I went. Then these acid-burnout types who had been around in ’68 came to see what was happening. We stayed for three or four weeks, and it turned into a big thing. We had readings and slept there and wouldn’t leave, and eventually they kept the place open, which was great, because the people who used it were these octogenarians who had been around in the ’30s and ’20s, really old New York, ultra-left, wonderful people.

“By my senior year, I was very involved with the anti-apartheid divestment movement, going to meetings, and directing for the first time.”

Kushner got involved with a theater group called the Columbia Players, and in a preview of his outsized ambition, he directed Ben Jonson’s Bartholomew Fair, which had 36 characters. Kushner sewed all the costumes himself.

“And there was no theater major,” Kushner said, “which was a great thing.”

The remark surprised me.

“I feel it’s a great shame that Columbia now has a theater major,” said this man of the theater.

I leaned forward with my face in my hands, concerned. “Tell me why.”

“Because it’s vocational training, it’s not a liberal arts degree. I’m sure that Columbia insists, as many schools do, that their theater majors take lots of academic classes, but I don’t think 18 is a good age to train somebody to be an actor because there’s a certain dismantling of the self that takes place. Good acting training should be sadistic. You have to unlearn a lot of what you think you know about acting, which is very entangled with your sense of self, in that the self that you present on stage has all sorts of complicated relationships with the self you imagine yourself to be and actually are. The difficult process of taking inventory of that and letting go of some of the things that you think make you attractive and appealing and good onstage and in public is very difficult. The first year in most serious acting training is a really hard year, and I think it’s ridiculous to think that people are going to do it when they’re 18 and away from home for the first time. You learn something, but I think you’ll learn it better when you’re four years older.

“Meanwhile, the liberal arts degree is one of the great inventions of Western civilization. It’s the perfect moment to become a brain for four years, and retrain, and learn, and I don’t think you ever get that back, I don’t think life is going to ever give you another four years when you’re allowed to just sit around and be confused.”

I still sat around being confused, but I saw Kushner’s point. I wished I’d read more in college, devoured more, been confused more.

There must be some Brecht plays on my shelf at home, I thought. Maybe tonight I’d curl up with Mother Courage. I then recalled something Kushner wrote in his “Notes about Political Theater” — “I do theater because my mother did theater.” I thought about the term “political theater,” and how it had a dual sense, and then I remembered that Lincoln had been shot in a theater and that Ronald Reagan was an actor.

Following the trail back to presidents, and to Columbia, and hardly knowing what I meant, I remarked to Kushner that lots of people thought Barack Obama ’83CC was a pretty good actor.

“Well, all politicians are actors in some ways,” Kushner said. “So is Lincoln. He was obsessed with Shakespeare, which probably along with the Bible was his favorite reading material. He loved actors and loved talking to actors about Shakespeare, and he loved reciting Shakespeare.” Kushner paused for half a second. “Of course, Obama’s an extraordinary performer, but I think anybody who thinks that he’s —” He veered from the thought, and went on with enthusiasm. “I think he’s an immensely exciting figure who on some level is working off the Abraham Lincoln playbook. He’s certainly one of the best writers we’ve had. So far he hasn’t produced a second Gettysburg Address, and nobody has written another Moby-Dick or Leaves of Grass or Emily Dickinson’s poems. It’s a different era. But I think he’s a brilliant politician, and, I think, possibly a statesman. I think he understands something about democracy that a lot of people have forgotten, which is that to exercise power, there’s a necessity of making compromises.

“The trick for Lincoln, who talked about this a lot, is that you hold on to some kind of moral true north, you keep your eye fixed on the ultimate values and goals toward which you are aspiring.”

After the interview I went to the office to do some research. That’s when I found out that Roy Cohn was Roy Cohn ’47CC, ’49LAW. Then I realized that Cohn would have been on campus at the same time as Allen Ginsberg ’48CC. Talk about poles. I read some more Kushner and went home.

Early that evening, my mother called.

“Happy Valentine’s Day!” she said. “Any plans tonight?”

“No, just staying in. Work to do.”

“Still on the fence.”

“Ambivalence expands our options,” I said, quoting Hendryk from Terminating, a short Kushner play. “Ambivalence increases our freedom.”

“I don’t know where you get these ideas.”

“Ambivalence is what made Lincoln a great president,” I said. “He was in touch with his doubts, and was willing to talk openly about them. That’s how he worked through extremely difficult questions.”

There was a pause. “You are not Abraham Lincoln.”

“That’s not the point.”

“So how was the interview with the playwright? What did he write?”

“His name is Tony Kushner, and his new play is called The Intelligent Homosexual’s Guide to Capitalism and Socialism with a Key to the Scriptures.”

“The what?”

“It’s set in Carroll Gardens, Brooklyn, in 2007, and it’s about a retired longshoreman, Gus Marcantonio, who’s a cousin of a historical figure, Vito Marcantonio, a socialist who represented East Harlem in the ’30s and ’40s.”

“A socialist?”

“Gus summons his three children to his house for a series of shocking announcements,” I said, paraphrasing the description on a postcard that I’d picked up at the Public. “The play explores revolution, radicalism, marriage, sex, prostitution, politics, real estate, and unions of all kinds. Oh, and two of Gus’s kids are gay. Shall I get tickets?” I didn’t wait for an answer. “Kushner said he was thinking a lot about Arthur Miller while he was writing it. He loves A View from the Bridge. That had a longshoreman in it.”

“Well, anything with a longshoreman sounds good,” my mother said. “When are you coming to visit?”

“Soon. I promise.”

Later that night, I grabbed an old anthology of plays from my bookcase. Inside it were some of Kushner’s heroes: Brecht, Eugene O’Neill, Miller, Tennessee Williams. I took the book and my voice recorder into my bedroom so that I could listen to Kushner’s words while I skimmed the pages.

I lay on my bed and turned on the recorder. Kushner’s voice rolled out. I closed my eyes and listened.

“One of the great gifts that one can get from the theater is that ability to see two things at the same time. When you’re watching a play, you believe in the reality of the thing you’re watching, while at the same time being acutely aware that what you’re watching is not real. You have to develop that double vision, that ability to be within the event and out of the event at the same time. That’s critical consciousness: the ability to see past the surface into the depths and inner workings of what’s gone into creating the surface effect.

“Theater can help with that, and to a certain extent you have to be able to see double when you’re looking at reality. Tayler would say you’ll be reality’s fool if you don’t.”