For the past fifteen years, legions of New York City schoolchildren have descended upon the ninety-nine-seat black-box theater in the basement of Schapiro Hall on West 115th Street to meet with William Shakespeare. Through a program called the Young Company, which was started by Brian Kulick, the chair of Columbia’s School of the Arts graduate theater department, third-year Columbia theater students visit local middle and high schools to conduct workshops and then, over two weeks, give ninety-minute performances of a Shakespeare play each weekday morning.

In 2018, the Young Company enlisted the Classical Theatre of Harlem (CTH), a nonprofit dedicated to theater production and education, to collaborate in a production of Romeo and Juliet. This year, CTH and the Young Company presented Twelfth Night, a raucous but melancholic comedy whose ingredients of gender switching, love triangles, bullying, and gleeful dissipation struck a present-day chord.

Sprinkled with scampering entrances and capering antics, Twelfth Night follows the maiden Viola (played by Yeena Sung), who is shipwrecked on the shores of Illyria, with her twin brother having gone missing in the wreck. Viola disguises herself as a man and finds work in the court of Duke Orsino (Clayton McInerney). Now called Cesario, she becomes Orsino’s favorite manservant — and secretly falls in love with him. But Orsino pines for Countess Olivia (Owala Maima), whose riotous household includes her boisterous, incurably pickled uncle, Sir Toby Belch (Titus VanHook) and her prudish steward, Malvolio (Jon Robin). When Orsino sends Cesario to convey his affections to the countess, Olivia falls for the messenger instead.

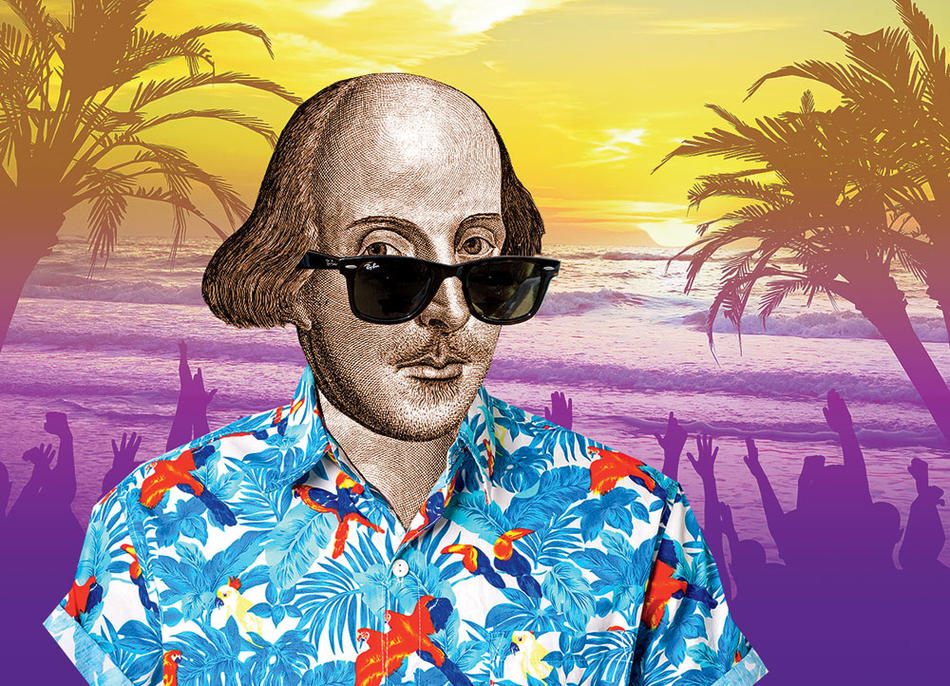

The director, Logan Reed, conceived Illyria as a coastal party town, with Sir Toby and his merry band of revelers sporting sunglasses, shorts, and tank tops. The high spirits of Olivia’s retinue proved catching to the audience — twelfth-graders on this morning — eliciting laughter, hoots, and peanut-gallery interjections. “It’s fantastic, because that’s how it was in Shakespeare’s day,” says Reed. “People threw fruit when they didn’t like a character. Offstage, characters talked to audience members. There was a back-and-forth, and that’s what we’re trying to do: make theater less stuffy and elitist. We’re saying, ‘Hey, we know you’re there, we know this is a play, and we’re inviting you in. You can scream, holler, check out, or whatever.’”

Though Shakespeare’s English can be baffling to uninitiated ears, Reed and his classmates managed to impart meaning. “There are physical jokes and verbal jokes,” Reed says. “Younger kids respond more to physicality, and that helps them access the language. If we match the physical and the verbal together successfully, some of the older kids will understand what Shakespeare is actually saying. Students also pick up on what’s relatable to their lives, like having an unrequited crush or not being able to reveal who you truly are.”

CTH associate artistic director Carl Cofield ’14SOA says that serving the community through theater has personal meaning for him as an actor and director of color. “The partnership lets Columbia students spread the gospel of theater in less affluent schools where the arts have been cut,” Cofield says. “I grew up with dreams of being an actor, but it was only when I saw someone who looked like me doing classical texts that I understood that there was a seat for me at the table.”

The benefits also extend to the Columbia students: the actors, directors, and stagehands, by working with CTH, receive Actors’ Equity Association contracts. “That makes them union members and opens professional doors,” says CTH general manager Ryan Patrick Ervin ’18SOA. For Ervin, who studied dramaturgy at Columbia, the biggest perk is the look on the kids’ faces. “To see young people connecting to Shakespeare for the first time is really powerful.”

After a flurry of frolics, pranks, blustery speeches, lovelorn odes, and songs sung by Olivia’s jester, Feste (Othello Pratt Jr.), Twelfth Night culminates with the appearance of Viola/Cesario’s missing twin, Sebastian (Jae Woo). With everyone unmasked and reconciled, most of the characters find a measure of fulfillment — and so did the kids, who clapped and cheered and then made an orderly exit to the school buses outside.

This year’s performances ran for one week instead of two due to the coronavirus outbreak, and the ensuing social isolation only underscored the power of the art form.

“The ritual of theater,” says Cofield, “requires you to be surrounded by other people and to experience something together with them in real time. That’s what makes it magical. And I think the times we’re in now will make us yearn for that again.”