Kelly Posner Gerstenhaber, a professor of psychiatry and the founding director of the Columbia Lighthouse Project, which promotes universal suicide screening, discusses her team’s latest work.

Suicide is an increasingly urgent public-health concern. What can you tell us about the long-term trends?

Over the past two decades, the annual suicide rate in the US has increased by about 30 percent. In 2020, which is the most recent year for which full statistics are available, nearly forty-six thousand Americans committed suicide. That’s more than the number who died in car crashes, who were killed by natural disasters like hurricanes or floods, or who were murdered. And it has been estimated that an average of 135 people are personally affected by each of these deaths.

Though suicides in the US have started to decline since peaking in 2018, the numbers are still high by historical standards, and the overall decline masks an unevenness in suicide risk across different segments of the population. While suicide rates have started to fall among white people of all ages, they’ve continued to rise for the most vulnerable groups, including people of color and the LGBTQ+ community.

It seems surprising that suicides would decline during the pandemic. Haven’t rates of depression climbed?

Yes, COVID-19 caused a spike in mental-health problems in this country, and in the beginning of the pandemic many experts predicted that suicides would increase. But that hasn’t happened, and nobody is certain why. I think part of the explanation is that we’re seeing the benefits of the work that mental-health professionals and others have done over the past decade to call attention to suicide as a public-health threat. Because so many people have been struggling during the pandemic, we’ve also been talking more openly about anxiety and depression, and this has helped to reduce the stigma that unfortunately still exists around these conditions. I suspect that many people who previously chose to hide their mental-health challenges now feel encouraged to seek help. It’s also possible that this extraordinary cultural moment that we’ve been living through has helped to hold down suicide numbers. People tend to come together in times of crisis, with families, friends, and neighbors going out of their way to reach out and express concern for one another — even if by Zoom or on FaceTime — and this can be a lifeline for people who are struggling with feelings of hopelessness and despair. This phenomenon tracks with historical research that shows that suicide rates drop during times of war, natural disasters, and public-health crises.

The Lighthouse Project’s mission is to promote suicide-risk detection and prevention. How do you do that?

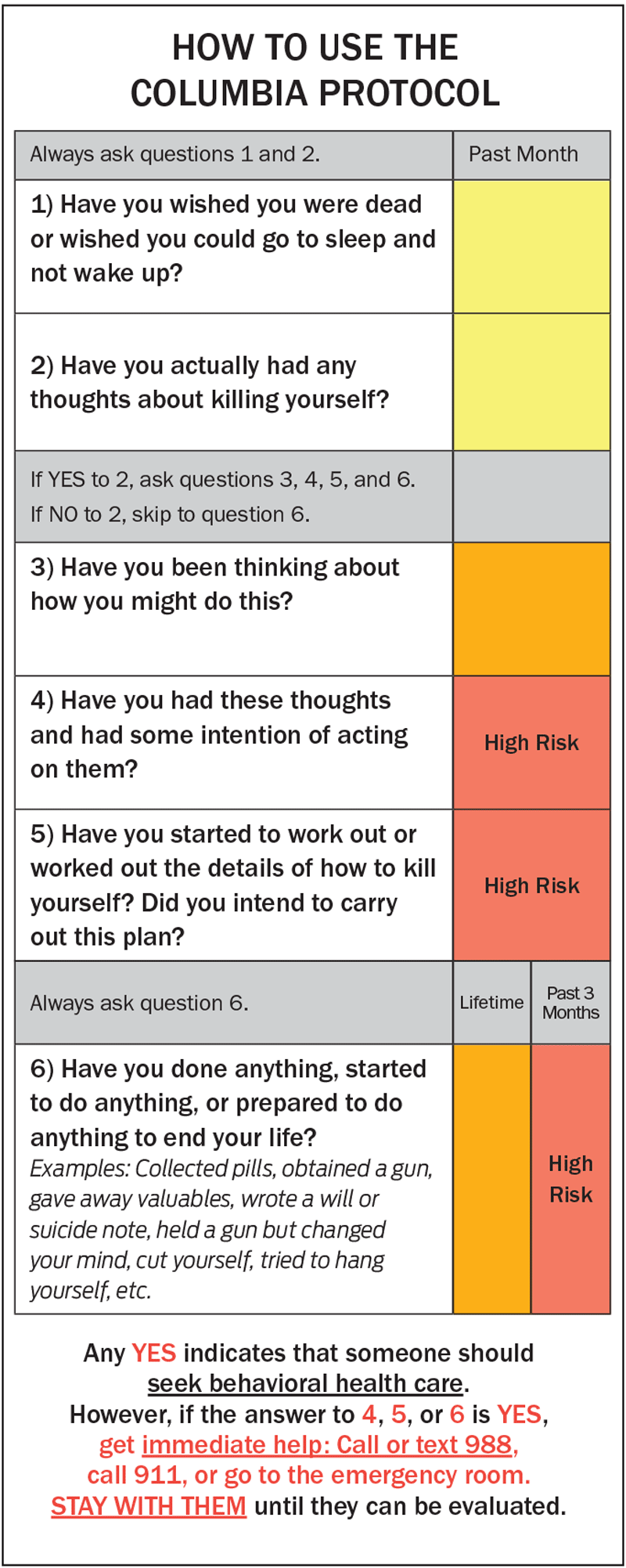

My colleagues and I created the Columbia Protocol, a short questionnaire that reveals if someone is at risk of dying by suicide and helps determine the level of intervention that’s called for, if any. Also known as the Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale, or C-SSRS, the screening tool is widely considered the gold standard for suicide-risk screening and detection, having been endorsed by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the US Food and Drug Administration, and the World Health Organization. Based on years of research on how to effectively communicate with people about suicidal thoughts and interpret their responses, the tool is accurate enough for clinical and research settings and yet simple enough for the layperson. It’s currently used by doctors, nurses, EMTs, police officers, teachers, school counselors, clergy, social workers, military personnel, corrections officers, and others across the US and in most other countries. Our goal at the Lighthouse Project is to get the Columbia Protocol into as many hands as possible and to encourage people to use it even in informal settings, such as with friends, family members, and coworkers, because we believe that combating suicide requires a community-wide approach. We’re trying to reach people where they work, live, learn, and socialize.

How does the Columbia Protocol work?

The person administering it asks a series of questions in plain and direct language, starting with “Have you ever wished you were dead, or wished you could go to sleep and not wake up?” and “Have you actually had any thoughts about killing yourself?” If the answer to either is “yes,” the person will ask additional questions to gauge the severity and immediacy of the risk, inquiring if the person has taken any concrete steps toward making a suicide attempt — such as collecting pills, getting a gun, giving valuables away, or writing a suicide note — and asking how recently they might have done so. The interviewer is then given options for helping the person, based on their answers. This can involve referring them to a suicide hotline or counseling services, or in urgent situations getting them to an emergency room. The questions might seem obvious, but their sequence and precise wording have been fine-tuned through intensive study, resulting in the most reliable, evidence-supported tool of its kind. Before the creation of the C-SSRS, we had no reliable way to determine a person’s imminent risk of suicide, which was a major barrier to prevention.

How do you know when to use it?

People who use the Columbia Protocol in the course of their jobs, like health-care and emergency workers, are trained to administer it routinely, so they don’t have to overthink that decision. For example, primary-care physicians across the US now ask patients if they’ve experienced any suicidal thoughts as part of annual checkups, treating it as a vital sign. First responders in hundreds of US cities and around the world use the tool to triage people who are in distress and identify those who actually need to be taken to the emergency room. Studies show that such efforts connect large numbers of suicidal people to urgent psychiatric care they wouldn’t otherwise receive.

I encourage people to use the questionnaire at home or on the job, whenever someone is acting unusually or showing signs of depression — which can include irritability, social withdrawal, anxiety, and loss of energy, as well as sadness — or even when meeting a stranger who’s obviously in despair. Once, while giving a talk to Connecticut state officials about the C-SSRS, I was told by a Veterans Affairs official about a janitor who’d used it to save the life of a veteran. And I’ve been told by parents — including the director of nursing at a major New York City hospital and a border-control official in Texas — that they saved the lives of their own children with the tool. I can’t tell you how many stories like that I’ve heard.

How do you broach the subject, exactly?

Be clear and direct. Many of us are afraid that if we ask someone if they’re suicidal, we’ll upset or embarrass them and somehow make the situation worse. In fact, we’ve found that most people who are suffering suicidal thoughts want help — they want someone to ask how they are, to listen to them, to express concern. It actually relieves their distress. We hear this over and over from people who have survived suicide attempts. Every situation is different, obviously. But as long as you approach the person gently and respectfully, and initiate the conversation in a discreet manner so that no one else overhears, there’s little reason to worry about offending them.

If someone is at imminent risk, you should bring them to a hospital?

Yes, hospital emergency rooms and many other types of medical facilities are equipped to handle psychiatric crises. You can also dial 911 and wait with the person until an ambulance arrives. Just don’t leave them alone. I should say that going to the hospital is necessary in only about 1 percent of instances when the Columbia Protocol is used. It’s more common for the screening process to result in a recommendation to connect the person to counseling or a hotline.

What are some other common misconceptions about suicide?

I think people often assume that someone who’s lost the desire to live is always going to feel that way, and that their efforts to intervene may not make a difference in the long run. But research shows that more than 90 percent of people who survive a suicide attempt will not go on to take their own lives, and most are suicidal for only a short time. The main cause of suicide, after all, is depression, which is a heritable and treatable medical condition. So by helping someone through a suicidal crisis, you are saving their life.

Another misconception is that by talking to someone about suicide you’ll put the idea into their head and help bring about that outcome. People worry about this especially with children. But again, research shows it isn’t true. Madelyn Gould ’80PH, a Columbia psychiatry professor who helped develop the protocol, published a seminal study on this matter in 2005, demonstrating that asking teenagers about suicide does not cause them to be suicidal. Multiple studies have since backed up her findings.

You said that suicide rates are still climbing for people of color. What’s behind this?

It’s well-documented that people of color in the US confront a variety of stressors that put them at increased risk of anxiety and depression. Encountering prejudice on a regular basis, whether this involves unintended microaggressions at school or in the workplace or more overt acts of racism, takes an extraordinary mental toll on people. On top of this, people of color are more likely to be economically disadvantaged, which can be a source of stress and limit their access to mental-health services.

How big a problem is teen suicide?

Suicide is now the leading cause of death for adolescent girls and the second-leading cause of death among all Americans aged ten to fourteen and twenty-five to thirty-four. Thousands of teenagers kill themselves annually in the US, as do hundreds of children under the age of fourteen. It’s not unheard of now for kids as young as five, six, or seven to intentionally end their own lives.

This is one result of a much larger mental-health crisis that’s been unfolding among American kids, considering that their rates of mood disorders have been rising for decades. Experts often blame social media, since it leads kids to spend less time in the company of friends and can heighten feelings of social inadequacy and loneliness while also creating new opportunities for bullying. What’s clear is that our society has been slow to respond to the problem. Too little money is invested in suicide-prevention programs in schools; too few psychologists and psychiatrists specialize in treating childhood depression; and too little space is available for depressed or suicidal youths in psychiatric clinics.

Perhaps our biggest failure is that we’ve denied the scope of the problem. Another one of my colleagues, the Columbia psychologist and author Andrew Solomon, wrote a devastating New Yorker article about this recently, describing how clinicians and parents alike often miss signs of suicidal thinking in young people because the prospect of children killing themselves is so unfathomable to us. But it’s happening. And to stop it, we have to talk to our kids about it.

Can the Columbia Protocol be used with children?

Yes, we’ve developed many versions of the Columbia Protocol for use with different populations, including one that’s appropriate for children as young as four or five. It rewords the questions, for example asking, “Have you ever thought about how to make yourself not alive anymore?” and “Have you ever thought about how you would make that happen?” Parents are often skeptical that children so young understand the concept of suicide — but they do. Research also shows that small but significant numbers of preschoolers suffer from clinical depression, although they’re rarely diagnosed and treated.

What impact have your efforts had?

The Columbia Protocol is helping to save lives. The US Armed Forces have adopted the C-SSRS, and the Marine Corps, after promoting the tool’s use by service members, spouses, chaplains, attorneys, and others as part of a broad public-health initiative in 2014, reduced suicides among active-duty personnel by 22 percent in one year. The Air Force has had similar success.

My team and I also work with a lot of communities, in the US and abroad, to tailor the Columbia Protocol to specific at-risk populations. For example, we’ve partnered with educators and police officers in Schenectady, New York, to help them identify adolescent girls who are at risk of suicide after being recruited into gangs and then feeling trapped in their circumstances. We’ve also worked with government officials in Saudi Arabia who intend to bring the tool to people throughout the Arab world, with an initial focus on reducing suicide rates among women and girls.

Once someone is identified as being suicidal, what are the treatment options?

Our most powerful tools in fighting major depression, and thus suicide, are antidepressant medications such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, or SSRIs. These drugs, which include Prozac, Celexa, and Zoloft, were once suspected to cause suicidal behavior in young people and in some adults. But years of careful analysis, including research that I led, has shown that this isn’t true. SSRIs are safe and effective and have saved countless lives, especially when combined with cognitive-behavioral therapy or talk therapy.

For people who don’t respond to standard treatments, there are new therapeutic approaches such as the use of psychoactive drugs like ketamine and psilocybin to help break negative thought patterns. Groundbreaking studies on the clinical potential of these substances have been conducted at Columbia University Irving Medical Center.

Columbia’s psychiatry department is also home to the Silvio O. Conte Center for Suicide Prevention, led by J. John Mann ’58GSAS, who helped create the Columbia Protocol. At the Conte Center, researchers are investigating the genetic and neurochemical roots of suicidal behavior in order to lay the groundwork for future treatment breakthroughs, while also studying the logistics of how best to deliver care. For example, research by Columbia psychologist Barbara Stanley has demonstrated the importance of having a personalized support plan in place for patients who are discharged from a hospital or psychiatric-care facility after having been suicidal. She’s shown that giving patients written reminders about the coping strategies they can use when they feel distressed and about who to call if they need help can dramatically reduce the risk of suicide in that post-discharge period.

Do you see a connection between rates of gun ownership and suicide?

Yes, of course. More than half of all gun deaths in the US are suicides. And we know that having an easy means to kill oneself makes people more likely to do it. This is why suicide-prevention programs put protective barriers on bridges and rooftops — because it’s proven that by restricting access to a means of suicide, you save lives, since most suicidal urges are temporary. If millions of Americans keep guns in their homes, it stands to reason that more people will have an available means to commit suicide.

There’s also a connection here to mass shootings. Studies have shown that many perpetrators of mass shootings in the US have a history of suicidal thoughts and behaviors, although their family and friends often recognize the warning signs only in hindsight. It’s possible that if we implemented suicide-screening programs more widely and connected more people with the mental-health services they need, we could prevent some of these tragedies.

Adult men still account for more than half of all suicides in the US. What can be done to help them?

The biggest obstacle to lowering suicide rates is the stigma that still exists around mental illness, and the idea that you’re weak if you ask for help. Men are quite susceptible to this notion. They’re much less likely to seek treatment for depression and four times as likely to kill themselves. We’re working with leaders in a number of male-dominated professions to encourage workers to speak with their colleagues about suicide using the Columbia Protocol. We’ve met with construction workers, firefighters, police officers, border-protection agents, airline pilots, and professional baseball players. Our message to them is “Some of your buddies are suffering in silence. Talk to them and let them know they’re not alone.”

This article appears in the Fall 2022 print edition of Columbia Magazine with the title "A Light in the Storm."