It’s 7:30 on a warm September night. A crowd of students and older music lovers clogs the sidewalk in front of Columbia’s Miller Theatre. The performance is sold out, so hopeful fans are looking for the odd ticket. Those who manage to get in are eager to experience — actually, they’re not precisely sure what. But they do know that the work they’re about to hear and see will be typical of the Miller in two ways: It will be thrilling and it won’t be onstage elsewhere.

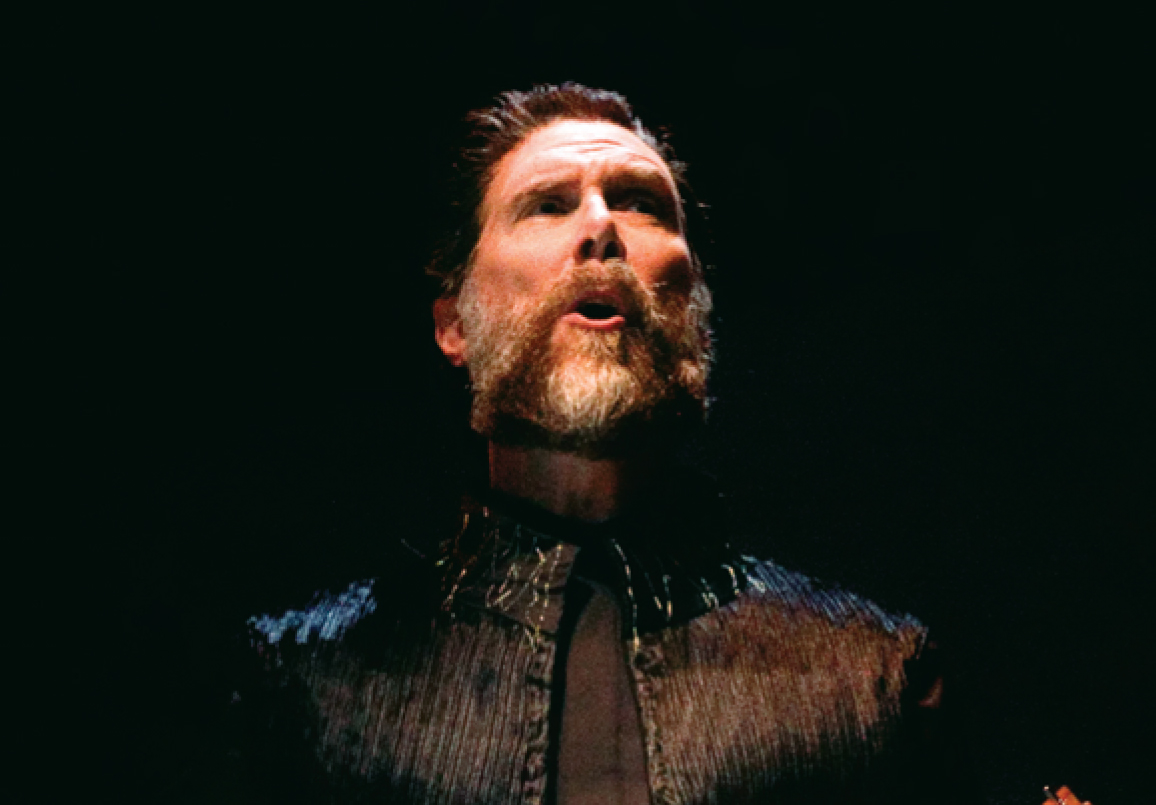

The U.S. premiere of the late Greek composer Iannis Xenakis’s Oresteia is the most ambitious production yet staged at the Miller. The work, based on the Aeschylus tragedy, is an amalgam of several musical forms: It’s a kind of cantata for soloist and choruses, dancers and projected images, small wind band plus cello, and a dominating two-man percussion battery. The singer alternates between his natural bass and a grating falsetto, while the instrumentalists, visible above the stage, slide from moments of fleeting beauty into passages of absolute aggression. The dancers slither in and out, adding a sometimes mysterious visual commentary to the sung and declaimed ancient Greek text. This is the fall of Troy imagined through Noh theater.

After the performance, dozens of conversations could be heard as puzzled and exhilarated concertgoers tried to make sense of the event that marked the beginning of the Miller Theatre’s celebratory 20th season, and the capstone of George Steel’s 11 years as the Miller’s executive director.

Steel, who left Columbia at the end of September to become general director of the Dallas Opera, “has made creative programming an art form in itself,” as Times critic Allan Kozinn put it. That programming has made the Miller one of the most vital music venues in New York today.

Columbia dropped in on Steel as he was packing up his office and asked him about Oresteia and about how he and his team invigorated the Miller Theatre.

“For the anniversary season,” he told us, “everything is sort of bigger and better. The Oresteia is the biggerest and the betterest — a kind of monster performance.

“It became clear to me very early on that for the Miller to do what everybody else does on a smaller scale was a guaranteed recipe for failure. So I focused on the University and the Miller’s history, I focused on what was missing from New York City, and I focused on concentrating the programs, making them so focused that a nonspecialist could enjoy them.

Columbia was once a dynamic scene for debuts of opera, dance, and instrumental works, Steel pointed out. “The opera Paul Bunyan by Benjamin Britten and W. H. Auden had its first performance at Columbia,” he said. “So did works by Copland and Barber. There’s a huge legacy of really progressive, interesting music. That’s where the real, important work of the Theatre had been historically, and we ought to be doing the same thing.”

New works again play an important role at the Miller. “Commissions are part of our Composer Portraits series,” Steel said. “Instead of just presenting five pieces by composer Arlene Sierra, as we will in March, we can also offer audiences a new piece we asked her to write. That really furthers what Lee Bollinger talked about when he became president, which is that the University should be commissioning new work.” The present season, Steel said, features eight world premieres.

Then there’s the one-composer approach. “This was a lesson I learned empirically,” said Steel. “More people are attracted to a one-composer program than to a two-composer program. Think of the great-artist retrospectives in New York. I wanted to present musical programs that did the same thing, that made living composers matter to the public.

“We found out that György Ligeti is a guaranteed sellout. The Philharmonic doesn’t play any Ligeti, certainly nobody would play an all-Ligeti program. But it turns out that in fact he’s a smash. And Conlon Nancarrow and John Zorn are composers for whom people go wild. Programming one composer was educational, it matched the University’s mission in a very profound way, and it answered a yearning need in New York’s cultural life.

“That’s precisely the role of the university: to act as a commentator on the society around it. Not that we spend all our time responding to what’s going on around us; of course what we do should be interesting and unexpected. We comment, in a sense, by identifying omissions of the broader musical culture. ‘Here’s the composer everybody else is too afraid to put on. Here’s the piece that’s so outrageous.’

“If it’s expected, it’s not going to be successful.”