This summer, when she wasn’t fighting to protect the wild ducks in the pond near her home in Lower Manhattan or tending to injured squirrels, Michelle Ashkin ’04GSAS was teaching teenagers about the dialects of whales and the problem-solving skills of crows.

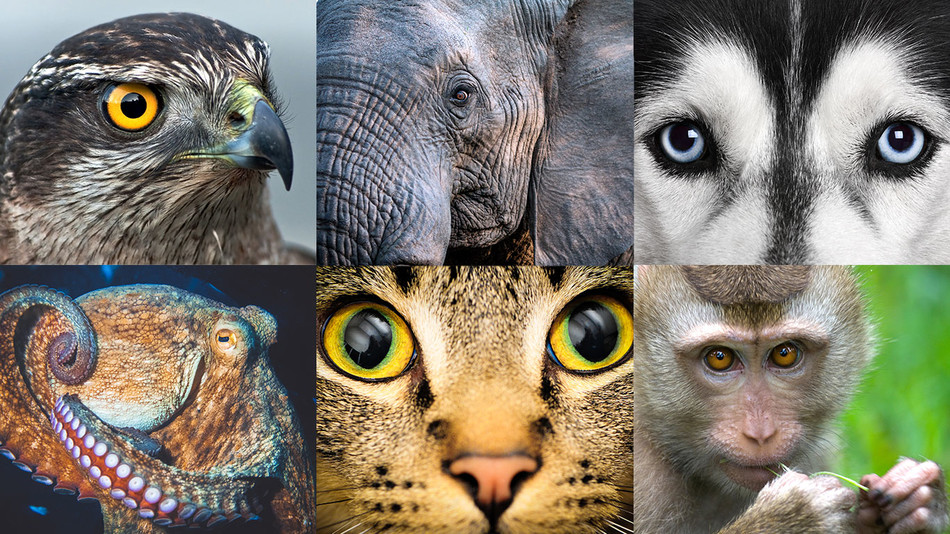

Ashkin’s intensive three-week course, offered through Columbia’s Programs for High School Students, is an introduction to the field of cognitive ethology — the study of animal minds. Inside the Animal Mind: What Animals Think and Feel invites students to explore the wonders of other species: the unearthly intelligence of the octopus, an invertebrate whose neurons are located mostly in its eight arms (“like having eight brains,” Ashkin says); the cleverness of the crow who drops stones in a drinking glass to raise the water level within reach; the speech of sperm whales, whose vocal clicks, called “codas,” are being analyzed by scientists who hope to decipher them, opening the Dolittlean possibility of language-based interspecies communication.

For Ashkin, the growing body of knowledge about animal cognition isn’t just a compendium of fun facts. It also tests the ethical basis of human dominion over other animals. “My whole mission in life,” Ashkin says, “is to raise awareness about our fellow creatures — and to get people to think about their relationship with them.”

To paint a fuller picture of that relationship, Ashkin begins the course with a history of philosophical and scientific thought about animals, citing, among others, Descartes, who saw animals as mechanical creatures lacking souls and the capacity to think or suffer, and Darwin, who in The Descent of Man posited that emotions and faculties such as love, curiosity, and reason were not exclusive to humans but were shared among species and differed only in degree. She also acquaints students with the giants of modern ethology, like primatologist Jane Goodall, zoologist Konrad Lorenz, evolutionary biologist James L. Gould, and naturalist E. O. Wilson, the last of whom has proposed setting aside half the land on earth as habitat for wildlife.

Ashkin’s students come to her class “thinking that cows are just hamburgers and wallets, and chickens are nuggets or wings,” she says, only to have these deeply ingrained notions upended. “When they learn that chickens purr (it’s called ‘trilling’) and love to be held, that they are smart and affectionate; or that cows panic and cry when their calves are taken from them, that they remember faces and people, form friendships, experience emotions, and love to play — it blows their minds.”

Ashkin’s course challenges “a whole history of a quest to separate ourselves” from other creatures. “We keep trying to find the holy grail of distinction between Us and Them,” she says. “For years it was tool use. But now we know that some animals use tools — not just chimps but also octopuses, crows, and elephants. Then it was a ‘working memory’ — the ability to briefly store and use small amounts of information. Well, animals have working memory too. Then it was the ability to self-recognize in a mirror. Well, certain animals — apes, elephants, magpies, dolphins — pass this test. Every time we think we’ve set the line of distinction between humans and nonhumans, they meet that line and we have to make another one. And so as we look for the thing that makes us human, that separates us from other animals, what we find instead is that we are more alike than we ever dared imagine.”

Such comparisons have long invited charges of anthropomorphism — the projection of human traits onto nonhumans — but the ground is shifting. “In the first part of the twentieth century, behaviorism — the theory that behavior is a response to stimuli in the environment — held an iron grip on animal-behavior studies in this country,” Ashkin says, noting that behaviorists relied solely on observable data and rejected intangible ideas like consciousness. “It was taboo even to consider that animals had emotions or any kind of internal subjective processes, because the nature of the subjective experience is not measurable. But today, with an explosion of research and new breakthroughs in artificial intelligence and neuroscience, the evidence of animal sentience is overwhelming.”

Of course, Ashkin acknowledges, the animal experience can never be truly knowable to humans. “How can we conceive of colors, sound, smells, and sensations that are not available to us?” she says. “We humans are very restricted in our senses — visually we detect a relatively narrow range of the electromagnetic spectrum, which precludes us from seeing ultraviolet and infrared wavelengths. Many birds can see UV light, as can insects, so the world looks very different to them. A hummingbird can see colors we cannot even imagine. A dog’s sense of smell is thousands of times more acute than our own. Elephants and baleen whales can hear low frequency or infrasonic sound waves that enable them to communicate over vast distances. And bats, dolphins, and whales can detect objects and food by using their biological sonar, which we call echolocation.

“Can we step into that existence and experience what it’s like to be another animal? No. The best thing we can do is to explore, as deeply as we can, the extraordinary and sometimes unfathomable ways that the millions of species on this planet interpret their world.”

Ashkin’s fascination with the minds of other animals didn’t start with a dog or a cat. It started with a wasp.

Growing up in Queens in the 1960s, Ashkin lived with cats, birds, and a rescue tortoise. “I was always curious about how animals lived their lives, how they made decisions, how they knew what they knew, and my pets instilled in me the notion that nonhuman animals are each different, with their own sets of needs, desires, and abilities,” she says. But it wasn’t until she was fifteen that an ordinary incident snapped her into a new level of awareness. She and her parents were out in the country in their mobile home, when a wasp got inside. It flew around and landed on the shower curtain. Ashkin saw it and called out for her mother, who ran in with a rolled-up newspaper.

“Then a strange thing happened,” Ashkin says. “We’re looking at the wasp, and the wasp literally looked back at us. It cocked its head, and my mother and I just stood there. Did we just see that? We moved, and the wasp followed our movement. My mother and I looked at each other, and it was an ‘aha moment’ for both of us: This is a being. This being sees us, or sees something — recognizes it, and is aware of it. How in the world were we going to kill it? We couldn’t. It became — there’s no other way to say it — it became a being, not a thing, not disposable, not ‘oh, we can kill it because there are hundreds more outside.’ So we found a cup, captured it, and let it go. And that was the beginning of my journey.”

Inspired by an insect, Ashkin began reading about the minds of animals. She learned about the cognitive abilities of chickens, cows, and sheep and did research on the sociability and intelligence of wolves. “Once you start to study this stuff, you can’t stop,” she says. “You just want to learn more.”

In 1992, Ashkin had a second aha moment. Having earned her master’s in education from NYU, she was working as a teacher at the new High School for Environmental Studies (HSES), the first public school of its kind in New York City. One day, she accompanied a group of students on a trip to Farm Sanctuary in Watkins Glen, New York. A 275-acre refuge for animals that have escaped slaughter, the sanctuary was founded in 1986 and is currently led by Megan Watkins ’97BC, ’00SIPA.

During a break in the tour, Ashkin went for a walk. She sat down on a grassy hill, taking in the breeze and the view, when she sensed a presence. She turned and saw three cows lumbering toward her. “I thought, uh-oh, are they going to get aggressive? Am I in their territory?”

She remained still, and the cows came over to her and, to her amazement, started to nuzzle her face. “I already loved cows as beings — I respected them, I didn’t want to eat them — but I never imagined that they were affectionate,” Ashkin says. “And that’s when I realized that it’s not just dogs and cats that are capable of affection. It’s across the board.”

Ashkin taught at HSES for ten years before her alarm at the ongoing destruction of habitats and species steered her toward a master’s at Columbia’s Department of Ecology, Evolution, and Environmental Biology, where her fieldwork included tracking endangered bobcats in New Jersey.

“Environmental protection is a lot more than clean air and clean water,” she says. “It is protecting essential ecosystems, developing land wisely so we can cohabit spaces safely with wildlife, and overhauling our factory-farming practices, which are horribly inhumane and environmentally destructive. It is all connected.”

After graduating from Columbia, she started a brand-new public school, the Academy for Conservation and the Environment, in Brooklyn. She was principal there for three years before she left to work more directly with animals — and to educate people about the need to protect them — at the Wild Bird Fund (WBF), the only wildlife rehabilitation clinic in New York City. Located at Columbus Avenue and West 87th Street, near Central Park, the WBF treats about seven thousand injured or orphaned creatures a year, including robins, red-tailed hawks, pigeons, falcons, songbirds, swans, and ducklings. In the basement there’s an operating room and a space where recovering birds practice their flying and foraging skills. “We have amazing rehabbers, and we try to release as many of the animals as we can,” Ashkin says. “It’s a real labor of love.”

As codirector of education at the WBF, Ashkin runs programs for schoolchildren and hosts field trips to the clinic. “When students visit us, we take them on a bird walk in the park, making sure they understand that these animals have very specific places where they live and very specific foods they eat, and that we have to make sure we don’t destroy the places they call home.”

Ashkin is aware that the phrase “animal rights” has negative connotations for some, and she doesn’t proselytize to students. In her Columbia course, she waits for the kids to bring up matters of ethics — which they invariably do. “These kids are from all over the world and are incredibly bright,” she says. “Many haven’t thought about these issues before, and it’s something they want to talk about.”

Such conversations are taking place globally, and not just in classrooms. This year, the UK Parliament introduced the Animal Welfare (Sentience) Bill, which contained provisions for an “Animal Sentience Committee” to assess the effects of government policy on animals. The Turkish Parliament approved a bill that would reclassify animals as living beings instead of commodities, calling for jail terms for animal abuse (instead of the standard small fine). In the US, the Supreme Court declined to hear a meat-industry challenge to California’s voter-passed Proposition 12, which gives pigs, veal calves, and egg-laying chickens more room to move around in their crates and cages. And when forty cows escaped from a Los Angeles slaughterhouse in June and were filmed galloping down a suburban street, many viewers rooted for their deliverance. (The herd was eventually corralled and returned to the slaughterhouse; two of the cows were spared and sent to a sanctuary.)

The topic is certainly timely, and Ashkin, while sensitive to its controversies, feels obliged to leave space for dialogue in the classroom. “It’s only fair to allow my students some discourse around these topics, because we all have to make decisions about how we live our lives,” she says. “The course raises more questions than it answers, which is perfect.”

Some of those questions, she admits, are difficult — and so are the answers, particularly in the context of extreme weather, mass extinctions, habitat destruction, overfishing, industrial-scale animal agriculture, and a zoonotic pandemic.

“As Maya Angelou famously said, when you know better, you do better. But doing better, in this case, means we need to transform industries; rethink what we eat, what we wear, how we live; and consider how our thoughtless self-centered human behaviors continue to endanger and extinguish so many species. How do we do that on a planetary scale? We can’t even treat each other with dignity and respect. What we really need is an earth-shattering paradigm shift.”

Until that happens, Ashkin will continue to dedicate herself to teaching humans about other animals. “I want to inspire people to ask the right questions and be stewards of wildlife, because these animals need our help,” she says. “Nothing brings me more joy than when I see people have that aha moment — the realization that other animals are beings in their own right.”

For Ashkin, such moments are not an end but a beginning.

“With new awareness comes the hard part,” she says. “What do I do now that I know my behavior is not aligned with what I value? For some people, the realization is enough to transform their lives. For others, it is a process. But awareness is the most important thing, because once you know something, you cannot un-know it.”