Václav Havel, writer, dissident, and former president of Czechoslovakia and the Czech Republic, will be artist-in-residence at Columbia this fall.

The residency, from October 25 to December 15, is being hosted by the Columbia University Arts Initiative (CUAI) and will feature two major public events: The Core Lecture on November 10, delivered by Havel; and a discussion on November 12 between Havel and Bill Clinton, moderated by Lee C. Bollinger.

“President Havel embodies the convergence of the arts and humanities with civic leadership, and we are honored to have him be part of our academic community,” Bollinger says. “It is especially notable that one of President Havel’s plays, The Garden Party, will be on the syllabus in Literature Humanities” — the first time a living writer has earned that distinction.

According to CUAI director Gregory Mosher, bringing Havel to Columbia has been an abiding goal for Bollinger, who sent Mosher to Prague in January to hold face-to-face negotiations with the playwright-turned-president. “Havel asked me how long he could come,” Mosher recalls, “and I said, ‘How about two years?’ He laughed, then said, ‘How about eight weeks?’”

In addition to working closely with the College and the faculty in the Core, Mosher and the CUAI are collaborating with colleagues at the School of the Arts, SIPA, and across the University to ensure that the entire community can benefit from Havel’s stay here.

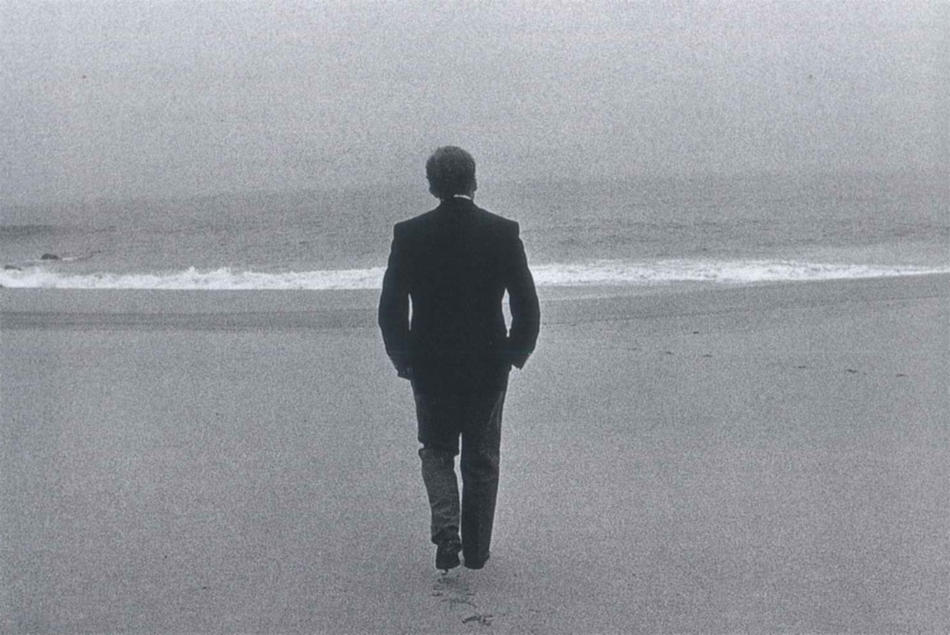

Standing at a cultural crossroads where theatre and poetry meet the Cold War and the fall of European communism, Václav Havel remains a unique figure in both politics and letters. Columbia recently asked Havel’s friend and translator Paul Wilson to tell us about working with this charismatic and complicated figure, whom Bollinger calls “one of the truly transformational leaders of our time.”

Notes from the Underground

By Paul Wilson

I went to Czechoslovakia to teach English in August 1967, almost exactly a year before the hopes raised by the Prague Spring were crushed by Soviet tanks. I ended up staying ten years, teaching, learning Czech, and, for a while, playing with a rock band called the Plastic People of the Universe. The band members got into serious trouble with the police in the mid-1970s because, in defiance of new regulations, their hair was long, their music was loud, and they played without a state-approved sponsor. An underground community of musicians and artists and writers had formed around the band, and it was through one of them that I first met Václav Havel, briefly, at a private screening in 1974 of some banned short films by the surrealist director Jan Svankmajer. I knew who Havel was, of course, but the screening was illegal and the audience dispersed rapidly when it was over.

When 12 underground musicians, including most of the Plastic People, were arrested in 1976 for antisocial behavior, Havel spearheaded a campaign to get them released. At the time, I clandestinely translated into English for Western reporters some press releases and letters of protest signed by leading dissidents, unaware that I was probably translating something Havel had written. The campaign worked: several musicians were released, and the rest received reduced sentences. The affair of the Plastic People then burgeoned into an important human-rights movement called Charter 77, a manifesto that called on the Husák regime to honor its commitments to human rights under the Helsinki Accords, which Czechoslovakia had signed in 1975. Several of my friends had signed the Charter, so the regime considered me guilty by association, and I was expelled from Czechoslovakia in July 1977.

After I moved back to Canada, my first major translation of Havel’s writing was his 1978 essay “The Power of the Powerless.” It was hard work, but not for the usual reasons. The irony of total censorship was that since dissident writers were no longer going through a censor, but publishing themselves, in samizdat, they were free to express exactly what they wanted and how they wanted, without resorting to evasive language to make their point. Havel therefore wrote his revolutionary tract in a clear, down-to-earth language for the average intelligent reader, and translating him on that level posed no problems. But at the same time, he was breaking new ground. No one had ever described that kind of tyranny before from the inside, or in such detail, and many of his words carried a different burden of meaning than their dictionary equivalents in English. Having lived in Czechoslovakia, I knew what that meaning was; bringing it into English, however, was another matter.

A small example: One of Havel’s key ideas is that totalitarian power, unlike a classical dictatorship, is impersonal. It is exercised through a system, an ideology, a bureaucracy, a police force, rather than through the personal magnetism of a supreme leader. Havel’s word to describe that agency was samopohyb — literally, “self-motion” — a neologism that derives, I think, from the word samohybny, meaning “self-propelled.” A literal translation, however, would not have conveyed the complexity of Havel’s idea, so I opted for variations of the word automatism and trusted that the context, and Havel’s own elaborations, would get his special meaning across. It was the Husák regime’s “automatism,” its impersonal penetration into every aspect of life, that made it so difficult to resist; but it also, paradoxically, meant that anyone who persisted in standing up to it — like the Plastic People, for instance — would disrupt that “automatism” and ultimately cause the system to break down.

I couldn’t ask Havel about this because he was serving a four-and-a-half-year prison sentence for “subverting the republic,” and though he didn’t know it himself at the time, he was working on his next book. Every two weeks, Havel was allowed to write to his wife, and in 1983 those letters were collected into a book he called Letters to Olga. The prison had strict rules about letter writing. Havel could write only about himself — a subject he had always tried to avoid — and his family, and the slightest transgression meant confiscation. Moreover, to baffle the censors, he often wrote in a deliberately obscure, philosophical, abstract, and convoluted language.

For a translator, this was hell. By the time I started work on Letters to Olga in 1986, Havel was no longer in prison, but I still couldn’t consult with him: I was persona non grata and could not travel to Czechoslovakia; he could not leave. I sent him a list of about three hundred queries by underground post. Two months later, he smuggled out a letter saying he couldn’t help me because he was no longer sure himself what he had meant. His strategy to beat the censors had been too successful: I was on my own, he told me. Fortunately, I was able to talk with close friends of Havel who were now living abroad and were familiar with the difficult Heideggerian idiolect he often used to encode his thoughts. It took me over a year to complete the translation; at times I felt as though I were in prison with Havel myself.

Again, censorship had unintentionally performed a good work: In trying to restrict Havel, the prison authorities had compelled him to open up a rich and hitherto untapped vein in his writing. His next book was refreshingly personal; he had found a way to balance his old clarity with a new and more intimate tone, and translating him was now pure joy. When Disturbing the Peace, his first real autobiographical book, was almost ready to be published, the Velvet Revolution had broken out, the powerless had taken power, and I could at last travel to Prague again. I was inside the Magic Lantern theater on November 29, 1989, when it was announced that the leading role of the Communist Party had been struck from the constitution. It was the point from which there was no turning back.

At a small gathering of the Civic Forum, of which Havel was the acknowledged head, there was champagne, and Havel gave a little speech, thanking everyone who had helped to make this moment possible. I was flabbergasted when he lifted his glass in my direction and thanked me as well, as his “friend and translator.” Two weeks later, he was elected president of Czechoslovakia.

On my last full day in Prague, I had breakfast with Havel in his flat while he ruminated on what was going on around him. “I’ve always been put off by revolutions,” he said. “I thought of them as natural disasters . . . not the kind of thing you can plan for or look forward to. And here I am, not only in a revolution, but right at the center of it.”

In his 13 years as president, Havel wrote all his own speeches, and I translated many of them into English, particularly the speeches he delivered abroad. Once, when we were talking in his office in the Prague Castle, he remarked that my translations made him sound “more elegant.” I’m not sure if it was a compliment or a criticism, but I will confess to making him sound more self-assured. Throughout his life, Havel has had the intellectual’s habit of qualifying his statements. His work in Czech is full of “I-could-be-wrong-buts.” When used too often, they can tax a reader’s patience. Taking my cue from “The Power of the Powerless,” where he almost never uses such phrases, I eliminated them from his writing. Have I betrayed him? I don’t think so, because under his shyness Havel has always been confident in his ideas, if not always in himself. I was just helping to bring out his true nature — which is, in any case, what a translator is supposed to do.

It is only now, as I work on his latest book, that I realize how difficult those 13 years in the Prague Castle were for him. The “experimental memoir,” called Please, Be Brief, is an interweaving of three elements: diary entries, an extended interview, and selected excerpts from his presidential memos. The memos were written on the fly, and they are more revealing, in a way, than anything else he has written. They show us his moments of despair and depression and self-doubt, his delight when things go well, and his white-hot and, at times, very funny anger when they don’t. They reveal the mind of a visionary tinkerer at work, a mind as much at home with the minutiae of a state banquet or designing improvements to the Prague Castle as with NATO expansion or the New World Order. I suspect that structurally it’s unlike anything a former head of state has ever written.

But then, none of Havel’s works is conventional. Just as he created an unconventional opposition movement to challenge the hideous conventionality of the regime, and reinvented the office of president to make it a showcase of the new democracy, so each one of his plays or books attempts to reinvent the genre in which it is written. And this is what I think is the most essential truth about Václav Havel: His courage to challenge authority or to accept the rigors of prison — or high office — comes from a deep and unshakable faith in the unique truth of his own experience.

Paul Wilson is a Canadian translator and writer. In addition to Havel’s work, he has translated many novels by Josef Skvorecky, Ivan Klíma, and Bohumil Hrabal.

Notes from Prague Castle

(From Havel’s Diary May 13, 1995)

On Friday I found our house beautifully decorated with flowers. Nevertheless, all that beauty suddenly ceased to please me, for I was compelled to pose the question: Did the kind Castle flower ladies decorate my home illegally? Or will I receive a bill on Monday morning from the PCA for 10,000 crowns? If I were to have to pay that much each week for such a wealth of floral decoration, I would give the money to some needy shelters for the homeless and buy myself one or two ordinary bouquets from a flower shop now and then. Or: B. and J. keep telling me how difficult it is for Mrs. Ouskova to launder my shirts, how much work she has, and how little money she gets for it, and how everyone is trying to solve this huge problem. For God’s sake, give Mrs. Ouskova what she deserves for her flawless ironing! Give it to her from my money, from the state’s money, from the general budget, from sponsors, or however you want, but don’t continually ask me about it or blame me for it. And if this problem is truly unsolvable, then tell me and I’ll find another laundress even though no laundress in the world is, understandably, as flawless as Mrs. Ouskova. [. . . .] Or: It was explained to me that I must shred any papers containing state secrets that I have written on or thrown away, but that the Castle cannot lend me the shredder and that therefore I must carefully gather together all these papers in a secret place and every once in a while secretly transport them to the Castle shredder. But really, I’m not here to play the fool for anyone. Etc., etc., etc. You will certainly understand that when I spend far more time on these pseudo problems than, for example, on the historic question of Czech-German reconciliation, I have a right to get upset. In short, sort these things out any way you like, and please, leave me out of it from now on.

Excerpted from Havel’s memoir, to be published by Alfred A. Knopf in spring 2007.