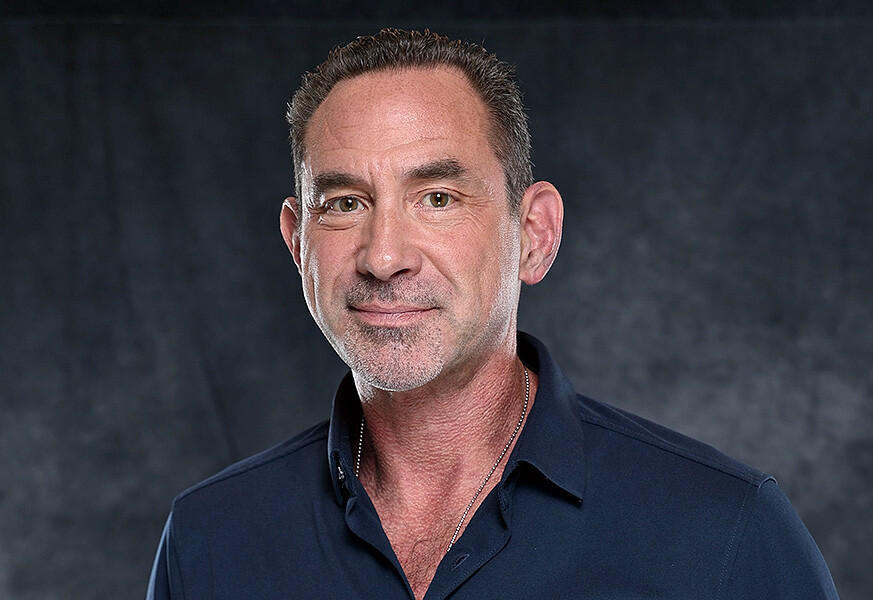

You began covering Mike Tyson in 1988 as a young reporter at the Daily News, two years after Tyson became the youngest-ever heavyweight champion. Did you imagine at the time that someday you’d write a book about him?

No. When I do a biography, I have to fall in love with the subject, and I was definitely not in love with Tyson. I knew my task as a tabloid columnist was to supply red meat. And Tyson became my designated villain, not without some justification.

What changed?

In 2012, I saw his one-man show, Undisputed Truth, in previews, before it went to Broadway. You get older and have your ass kicked a couple times in life, you become more tuned in to things. Watching Tyson onstage talking about getting his ass kicked, I found myself holding back tears.

After the show, I met with him and asked him if something bad that I had once written about him was true. He admitted it was. Then he looked at me and said, “How did that make you feel?” I thought, Who’s asking the questions here? I told him about the adrenaline rush of covering a big, fast story for a tabloid paper, how it was like a drug. And he nodded. And I thought, This is a different guy. It’s not the monster. I can empathize with this guy.

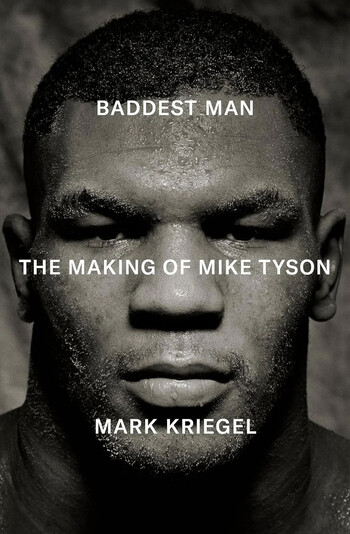

Your book covers Tyson’s early life in Brooklyn and in Catskill, New York, where he lived with his trainer, Cus D’Amato, and ends in 1988 with the Tyson–Spinks fight, when Tyson was twenty-two. Did you intend for this to be a single volume?

The truth is, I didn’t want to write a biography. I wanted to write a slim, elegant book about writers and fighters. But Tyson generates so much damn story. I had three hundred manuscript pages, and Tyson was seventeen.

Your book is still about writers and fighters, and about how journalists you admire, including Norman Mailer, Gay Talese, and Pete Hamill, contributed to the Tyson myth. Why are so many writers drawn to boxing?

Any story begins with a need for conflict, and boxing is ritualized, stage-managed conflict. Your themes are explicit and your protagonists are naked metaphorically and almost literally. And chances are that whatever made these two fighters goes back to some dysfunction in their backstory. Each protagonist carries his story into the ring with him that night, and when they confront the other, it’s a perfectly set up drama.

One of the main dramas in the book is between Tyson and D’Amato.

Cus had taken this kid in from juvenile lockup, and all he was asking of Tyson was, Make me live forever. It’s a Faustian bargain: You can have anything you want, Kid, but you have to be the greatest, the youngest, the baddest. You have to make me live forever. When I posed that to Tyson, his response was, “Well, didn’t I?” And my question is, “Yes, but at what price?”

What separated Tyson from his competition in the 1980s, when he was knocking everyone out in the first or second round?

In addition to his physical gifts, his real genius was his ability to refract his own fear onto his opponent. Guys were scared to come out of the dressing room. Tyson was scary to begin with, but the idea of him — and the way that he exploited this in an opponent’s mind — was infinitely more terrifying.

Your book ends in Atlantic City at Tyson–Spinks: there’s Tyson, Don King, Spinks’s manager Butch Lewis, and, front and center, Donald Trump.

It’s like a grand Sabbath of narcissists. When I look back on the Tyson of ’88, I see the genesis of 1990s tabloid culture. The latter section of Tyson’s career, when he was declining emotionally and physically, gets so much attention because he played the villain to such great mass delight. The idea of Tyson as the scary guy was so lucrative that he was obliged to be that guy.

How has your own idea of Tyson changed over time?

I realized that it’s much better to judge him by what he survived: a broken mother who died young, an absent father, Brownsville, molestation, incarceration, boxing itself, an all-consuming fame, Don King — the list goes on. Typically, the third act in a fighter’s life is the tragic one. Tyson’s has been the most unlikely triumph.

This article appears in the Fall 2025 print edition of Columbia Magazine with the title "Writers and Fighters."