The parallels between religion and sports are hard to miss: fans are the flock, coaches the priests, athletes the gods, stadiums the temples. There is chanting, praying, singing. There is ecstasy and transcendence, defeat and deliverance. There is ritual. There are rules. There is sacrifice. And when the impossible happens, it is recalled in sacred terms: the Hand of God, the Immaculate Reception, the Miracle on Ice.

But for Gotham Chopra ’97CC, a writer, filmmaker, and producer who cofounded, with NFL greats Tom Brady and Michael Strahan, the sports-media company Religion of Sports, the comparison misses the point. “Sports aren’t like religion,” Chopra says. “They are religion.”

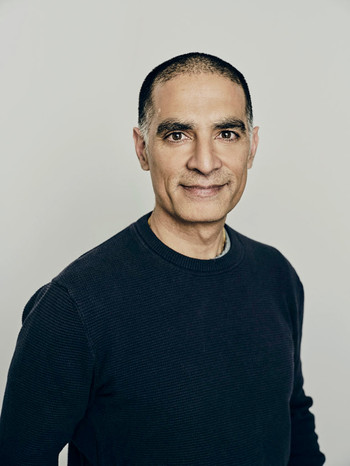

And Chopra, forty-nine, is a true believer. For more than a decade, he has written, directed, and narrated documentary films and docuseries that reveal the power and profundity of sports, whether on the scruffy soccer pitches of remote villages in developing nations or in thunderous multimillion-dollar arenas where elite athletes vie for immortality. Chopra is, above all, a storyteller, and it’s his feel for the human pulse at the heart of the action that makes his narratives so emotionally rich and revealing — and universal.

In his effort to convince even the most ardent skeptic that sports matters, Chopra has gone to the mat by invoking — and interviewing — the gods themselves: Brady, Serena Williams (tennis), Simone Biles (gymnastics), Lindsey Vonn (skiing), the late Kobe Bryant (basketball), Conor McGregor (mixed martial arts), and many more. There is something in Chopra’s appreciation of his subjects, and in his thoughtful manner, that brings these world-class athletes out of their shells. They share their secrets, their strategies, their vulnerabilities, their intense competitiveness, and their passion for perfection, embodied in an obsessive focus on practice and detail. Chopra interweaves these unguarded confessions with thrilling footage of athletic high drama.

“Every athlete, from Kobe to Tom to Serena to Simone, addresses this question: how do I do what I do? And the answer is devotion to craft,” Chopra says. “To perform at the highest level, to reach that elite status, requires discipline. And that is spiritual. We tend to think of spirituality as just this elevated state of awareness. But really it’s about repetition, process, and structure. That’s what religion gives us. And I see that in these athletes.

“Take Serena: she has thirty-three Grand Slam finals across twenty-plus years, and she won twenty-three. She’s the greatest ever. And I asked her, ‘What’s the one quality that enabled you to have all this success?’ And she said, ‘I guess it would be showing up and doing the work. I can’t tell you how many times I woke up and didn’t want to go to the court to practice. But I did — I showed up and I did the ritual even when I didn’t want to.’”

But what really sets these performers apart, Chopra discovered — the thing that so often determines their fate — is how they respond to failure. “Tom always says, ‘It’s not about the seven Super Bowls I won. It’s about the three Super Bowls I lost. How did I learn to pick myself up?’ And that’s what faith does. In our darker moments, it’s what enables us to keep on going.”

“To perform at the highest level, to reach that elite status, requires discipline. And that is spiritual.”

Brady is featured in two of Chopra’s productions, both of them winners of Sports Emmys: Tom vs. Time, part of a “Versus” franchise for Facebook Watch that includes Stephen vs. The Game (with Steph Curry) and Simone vs. Herself (with Simone Biles); and Man in the Arena: Tom Brady, a gripping ten-part epic for ESPN+ packed with wisdom, revelations, and parables. Whether he’s portraying the brotherly rivalry between the backup quarterback Brady (a sixth-round draft pick) and the injured All-Pro starter Drew Bledsoe; or head coach Bill Belichick’s blunt, Solomonic decree, after Bledsoe’s recovery, to continue to start young Brady instead; or themes of loss and vengeance and redemption, of team over the individual and the individual over himself, Chopra shows us that hard work and a positive attitude are the name of the game, and that there are no shortcuts to greatness. “There’s no easy climb,” Brady tells us. “No one’s dropping you at the top.”

Chopra’s climb up the mountain of sports media began in childhood. The son of Indian immigrants, Chopra grew up in Boston, where the home teams — the Celtics, the Red Sox, and the Patriots — formed his holy trinity. Here was a faith open to anyone, and membership required merely a rooting interest; in return it offered community, catharsis, and the spectacle of real-world myths and wonders.

Chopra was the only believer in the family. Neither his parents nor his sister shared his obsession. His father, Deepak Chopra, the physician and integrative-medicine advocate, never took him to a ball game, but he always supported his son’s interests. “Contrary to the stereotype of immigrant parents who say, ‘You have to become a doctor or a lawyer or an engineer,’ my father always said, ‘Do what you’re passionate about. Find your purpose,’” Chopra says. “My dad’s my biggest cheerleader.”

In 1975, the year of Chopra’s birth, the Red Sox lost a heartbreaking World Series to the Cincinnati Reds — a blow that would help cement the mythical Curse of the Bambino, a championship drought that began in 1919 when the team sold Babe Ruth to the New York Yankees. Chopra suffered through the Sox’s cruel 1986 World Series loss to the Mets and the soul-crushing 2003 defeat at the hands of the archvillain Yankees for the American League pennant. And so in the 2004 American League Championship Series, when his blighted ball club, down three games to none against those same Yankees, proceeded to win four in a row — the first Major League team ever to complete such a comeback in the postseason — Chopra felt he had witnessed an honest-to-God miracle.

But his real salvation had always been basketball. He bled green for the great Celtics teams of the 1980s, enthralled by the wizardry of Larry Bird and the rivalry with the Los Angeles Lakers. No house of worship was more magnificent to him than Boston Garden (the Celtics’ home, demolished in 1998), no taste sweeter than victory over Magic and Kareem.

When it came time for college, Chopra wanted to leave Boston for New York. He applied to Columbia, eager to wrestle with the Core Curriculum, and got in. “My grandmother, my father’s mother, would always tell us, ‘Pursue Saraswati, the goddess of knowledge, and then Lakshmi, the goddess of wealth and prosperity, will become jealous and she will chase you.’”

Chopra entered Columbia in the fall of 1993. That summer, his father, who was then relatively unknown, made his first appearance on The Oprah Winfrey Show and exploded into the popular culture, bringing the idea of spiritual well-being to the fore. “My dad has had a profound influence in every aspect of my life, but particularly in Religion of Sports,” says Chopra. “Again, my dad was not a sports fan. But these days it’s interesting: athletes have figured out how to take care of themselves physically, and what they really want now is to talk about the mental and emotional side. When you have success and money and people coming at you, life can become really hard to navigate, and a lot of these athletes are searching for mental, emotional, and spiritual relief.”

“When making a film I always ask myself: What’s the bigger story here? What’s the mythical story?

But that was all still far away in 1993. As an undergrad at Columbia, Chopra studied English, religion, and film — the three pillars of his future occupation. He also met his wife, Candice Chen ’97CC, ’02VPS, and a lifelong friend, Jay Adya ’98CC, ’05BUS, who would be instrumental in the creation of Religion of Sports. In Hamilton Hall, Chopra met Homer and the Bible, the literary ground in which he would later root his modern pop-culture sports stories. “When making a film,” says Chopra, “I always ask myself: What’s the bigger story here? What’s the mythical story? What’s the archetypal story?”

After graduation, Chopra looked for on-air TV work and got a freelance gig hosting a show about paranormal phenomena called Strange Universe. That attracted the attention of an agent at United Talent Agency. “I was not yet conscious of the fact that a lot of people were getting to know me because of my dad,” Chopra says. The agency signed Chopra, then twenty-three, and got him a job with LA-based Channel One News, where Anderson Cooper and Lisa Ling had gotten their starts.

“One of the executives over there was a big fan of my dad’s,” Chopra recalls, “and he had this notion of, ‘We’ll spiritualize the news, and it’ll be softer and a little more progressive.’ I picked the job because it was a great job and an interesting opportunity. Then I got there and said, ‘I want to do what Anderson and Lisa are doing.’”

It was a bold play, and Chopra got his wish: for the next few years he did on-camera reporting from hot spots in Afghanistan, Pakistan, Iran, Chechnya, and the Middle East. “It was the antithesis of the expectation for the son of Deepak Chopra,” he says. “It was like, ‘I’ll go anyplace where there’s conflict.’”

In his often-grim travels, however, Chopra noticed something remarkable. “In all of these places, there was so much anger and conflict and resentment — until you started talking sports,” he says. “Back then, it was Michael Jordan, the ‘Bad Boy’ Detroit Pistons, or David Beckham and Manchester United. Sports was a way to cut through and connect. Everybody had an opinion. It’s like India and Pakistan in cricket: there’s this holy war, and the only time they ever stop firing rockets at each other is during cricket matches. Everybody wants to watch cricket. No matter where you go, no matter what side, people are sports fans.”

Chopra left Channel One in 2005, and the following year he cofounded a digital-comic venture called Virgin Comics (Sir Richard Branson was an investor), later Liquid Comics, which by 2011 grew into Graphic India, a digital-comic and animation company whose mission is to create inspiring stories and superheroes based in Indian myth and aimed at the country’s 550-million-strong youth market. Then, in 2012, Chopra’s life took a sudden turn: a friend invited him to a philanthropic event, and Chopra found himself seated next to LA Lakers star Kobe Bryant.

Chopra and Bryant were around the same age, and they chatted about the Celtics–Lakers battles of the 1980s. “Kobe said, ‘I want to show you something,’” Chopra recalls. “He invited me to his house in Newport, where he had these old VHS tapes of Celtics–Lakers games that his grandfather had sent him when he was growing up in Italy [Bryant’s father, Joe Bryant, had played basketball in the Italian league]. He said, ‘I want to show you why Larry Bird is the greatest pump faker: look at his eyes.’ And it turned into this hours-long master class. Kobe was an amazing storyteller and mythmaker, and he had this idea about inspiration. He was like, ‘I play basketball the way Michelangelo paints the Sistine Chapel,’ and ‘When I play ball, I hear Mozart,’ and he wanted to do a documentary on that. But I didn’t really know how to make sense of that as a film.”

By 2013, with the rise of ESPN’s sports-documentary series 30 for 30, Chopra had taken the dive into the genre. ESPN hired him to do a 30 for 30 on Indian cricketer Sachin Tendulkar, and it was during a three-week shoot in India that Chopra saw on TV that Bryant, thirty-four, had ruptured his Achilles tendon — a potentially career-ending injury. “And I saw Kobe in the locker room saying, ‘I am going to come back from this.’ So I called him that night and said, ‘This is the idea for the documentary: we follow your comeback.’ A week later, when I got back to the States, we started it. The project ended up taking two years, and we grew really close.

“Kobe was actually really difficult to work with, because he’s so opinionated and combative, just like on the basketball court, and he would push me and push our team. I traveled with him to China and all these places, and the way he impacts people beyond basketball — I used to always joke with him, like, ‘There’s the religion of sports, but there’s also the cult of Kobe.’ My experience with him was a catalyst for a docuseries idea that would become Religion of Sports. I realized that all the things that my dad had started to explore in his career and life around spiritual and wisdom traditions — all of it existed in sports, and that became the thesis for the show.”

Chopra sold the show to AT&T’s Audience Network. Meanwhile, he had become friendly with Strahan (who had recently become a host of ABC’s Good Morning America) and Brady (pushing forty and still playing football at the highest level), and in 2016 he invited them both to sign on as executive producers.

“I always understood the ‘religion of sports’ idea as a fan — joining a community that’s bigger than you, having faith in the irrational, surrendering control of your emotions,” Chopra says. “But these guys had it from the other point of view, like, ‘Man, I know what it’s like to be in the middle of the field and everybody’s invested in me, so how do I find that space in myself to be my best?’” Brady and Strahan loved the idea and became Chopra’s partners.

Chopra was assembling a dream team, and he wasn’t done. His friend Jay Adya, now a sports-media investor, told Chopra he should think bigger than a series. Chopra agreed: there was Religion of Sports the show, but there could also be Religion of Sports the concept — a media brand that could produce all sorts of stories. Yes, Adya told him, but you’ll also need someone on the business end, someone who can raise capital. And Adya knew just the person: Ameeth Sankaran ’05BUS, a sports-loving entrepreneur from Texas. Adya made introductions, and Sankaran became Chopra’s business partner and the CEO of Religion of Sports.

“Gotham had just set up the first season of the show Religion of Sports and started to conceptualize building this out as a company,” says Sankaran. “What could the company look like? How big would it be? Would we focus purely on unscripted material? Then we raised our first small round of capital and things became very real.”

Today, Religion of Sports has a team of fifty, offices in LA and London, its own postproduction facilities, and many broadcast and streaming partners. In April, the company took its first foray beyond sports — a four-part series on rock star Jon Bon Jovi called Thank You, Goodnight: The Bon Jovi Story — and this summer it will release the docu-series In the Arena: Serena Williams. Earlier this year, Chopra published a book, Religion of Sports: Navigating the Trials of Life Through the Games We Love. Chopra has always seen sports as one of life’s great teachers. “That’s why we put our kids in sports programs,” he says. “Not because we believe they’re going to become Steph Curry or Serena Williams. But because we learn from sports — we learn about teamwork, leadership, the value of practice. We learn how to win, how to lose, and how to get back up after falling.”

As the religion’s biggest booster, Chopra has heard the doubters. Usually, he says, people will object to any conflation of sports and religion on the grounds that sports is tainted by scandal and corruption and violence and money. But Chopra sees no contradiction. “There’s a dark side of sports, just like there’s a dark side of religion,” he says. And he points out that when it comes to the double-edged sword of tribalism, sports gets it right: “We settle our differences on the field, and then we shake hands.”

One of the most poignant moments in Chopra’s filmography comes in a Religion of Sports episode titled “The Promised Land,” about two high-school football teams on opposite sides of the southern US border. Chopra takes us into the lives and communities of the two teams — one from Tornillo, Texas, the other from Juárez, in the Mexican state of Chihuahua — as they prepare to face each other in Tornillo. Going back and forth across the border fence, Chopra paints a portrait of such depth and sensitivity that the viewer’s sympathies are evenly divided. How do you root for both teams?

Then comes the game, under the Friday-night lights. It’s never really close. Amid joy and despair, time expires on a lopsided score. Victory. Loss. We feel the tug of both. The two teams shake hands, and then, in the middle of the field, the players gather together to kneel and listen to the two coaches. The Juárez coach, humble in victory, delivers his speech in Spanish: “At the end of the day, we are football players and football brothers. Nothing will separate us. Not a wall, not a river. Nothing. Those who create borders are only men. And as long as we don’t want to be separated by those borders, it will never happen.”

The American coach, dignified in defeat, then moves into the middle of the scrum. The players on both sides stand and crowd around him, and they all raise their helmets in the air. “Thank you guys for coming,” the coach says, “and good luck in the rest of the season. Everybody good?” Yes, everybody was good. “‘Football’ on three. One. Two. Three —” “Football!”

There’s nothing more to say. Chopra jumps to a long overhead shot of the field, which glows emerald green in the Texas night. Then he cuts to black.

It’s a moment of storytelling grace, but Chopra — like Brady, like the kids from Juárez — would never claim the success as his alone. Every believer in the religion of sports knows that winning is a communal affair, that athletes need their teammates, coaches, and fans to lift them up, and that heroes aren’t born but made.

“As a filmmaker I get a lot of credit, but I’m only as good as the people I surround myself with,” Chopra says. “And I learned this from Tom, who will say, ‘I’m the quarterback, I got all the credit. But it was the coaching staff. It was my offensive linemen. It was my receivers. It was the defense keeping games close enough so that what I did made a difference.’

“Tom always says, ‘The team, the team, the team.’ And I agree.”

Blessed are the athletes: How sports was once embedded in religious ritual

It was 1969, and Allen Guttmann ’56GSAS was seated in a soccer stadium in Berlin amid sixty thousand screaming fans. Guttmann found it interesting that Germans were crazy about soccer just as Americans were fanatical about other sports. He started to write about the phenomenon, and his research quickly went beyond a comparison of the two cultures. He discovered a much bigger divide. The resulting work, From Ritual to Record (Columbia University Press, 1978), examined the difference between modern sports and the sports of all previous eras.

“The most important difference is that in the past, in many societies, sports were a part of religious worship,” says Guttmann, who is professor emeritus of English and American studies at Amherst College. “The ancient Olympic Games were part of the worship of Zeus. The Apaches of the Southwest US had an annual foot race for adolescent boys that was meant as a religious ritual. Mayan religion included ball games in which the losers were sacrificed [some scholars believe that it was the winners who were sacrificed]. Sumo was part of the Japanese Shinto religion.

“But this is absolutely not the case in modern sports, unless you want to define them as a secular religion — which is actually what Pierre de Coubertin [founder of the modern Olympic Games, which date to 1896] did on many occasions.”

According to Guttmann, the connection between sports and religious rites began to fray in late antiquity. “Roman sports had been, to some degree, a part of religious ritual, but early Christians found this horrific. After the fourth-century Roman emperor Constantine converted to Christianity, the Olympics were banned and the site was destroyed.”

Suspicion of sports continued through the Middle Ages, says Guttmann, when the Catholic Church forbade them. In the early seventeenth century, English Puritans attempted the same. “King James I decreed that sports were fine on Sunday, if the pious went first to church. So it was clear that there was separation between sports and religion. Yet in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, fundamentalist Christians still denounced modern sports as pagan ritual.”

But there was another force transforming the character of sports, Guttmann says. The Romans began to count the number of times a charioteer won a race. In 1695, England’s Samuel Watson invented the first stopwatch. Sports was soon captured by a kind of cult of quantification, in which numbers and records, not religous ritual itself, became sacred. By the modern era, statisticians had devised batting averages, field-goal percentages, passer ratings. Technology allowed race times to be measured to the thousandth of a second. Call it the religion of stats.

In contrast, neither times nor distances were measured at the ancient Olympic Games. “They didn’t quantify anything,” Guttmann says. “The games were for Zeus, who didn’t worry about how fast his worshippers ran or how far they threw a discus. He cared only that some athletes won and others lost.”

This article appears in the Spring/Summer 2024 print edition of Columbia Magazine with the title "Of Gods and Games."