It’s not unusual for people to donate their bodies, or parts of their bodies, to science. In fact, almost 170 million Americans are registered organ donors, and people with specific medical conditions often donate their bodies for disease research. But giving your body to a medical school so that students can learn anatomy — the fundamental basis of medicine — is not an option you can check off while renewing your driver’s license. That may help explain why many institutions, including Columbia, are currently experiencing a body shortage.

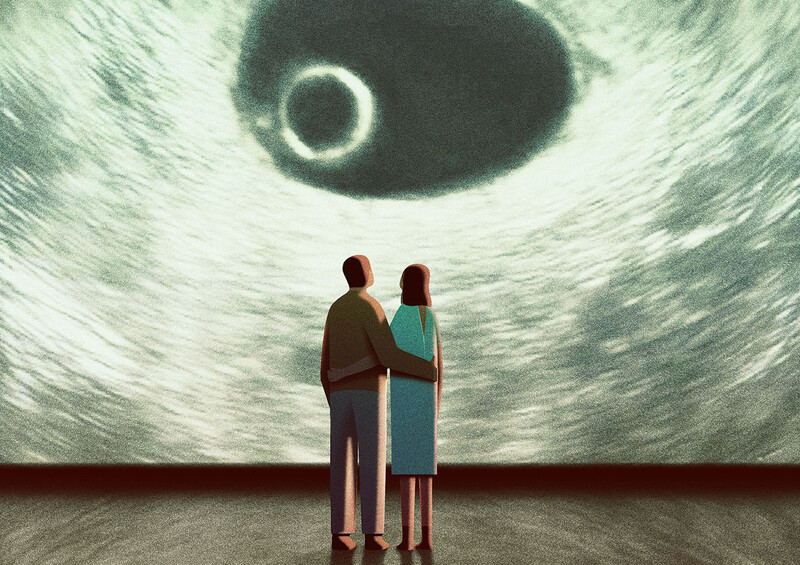

This is an urgent problem, because for first-year medical students, a cadaver is the ultimate learning tool. “In a sense, that body is a student’s first patient,” says Paulette Bernd ’77GSAS, ’80VPS, director of the Anatomical Donor Program at CUIMC. Bernd, who runs the clinical gross-anatomy course at Columbia and gives most of the lectures, maintains that regardless of the increasing sophistication of 3D computer models, there is no better teacher than the human body itself. “An actual body is obviously more realistic,” she says. “The artery or the nerves or the muscles might not look like they do in the textbook, so there’s an act of discovery that students have to do on their own.”

At Columbia, all first-year medical, dental, and physical-therapy students take a human dissection course, and the rewards of studying real bodies can’t be overstated. “For those who are going into surgery — which is a pretty good number of medical students here — it’s invaluable,” says Louie Kulber, a second-year MD-PhD student. “They’re never going to have another opportunity to do a full-body dissection, where it’s OK to make mistakes.” Then there’s the human side: “You have to care for your cadaver and keep it properly covered. You have to make sure you’re being respectful.”

Last spring, Kulber helped organize Columbia’s annual anatomical-donor memorial service, which dates to the 1970s. More than 150 students and faculty gathered in the Vagelos Education Center at CUIMC to honor the donors with whom they had become so powerfully connected. Bernd, along with University chaplain Jewelnel Davis and dean of students Jean-Marie Alves-Bradford, offered remarks, and then the students got up to talk about “the incredible selflessness of the donors,” Kulber says.

During Bernd’s course, which runs from August to December, two moments of silence are observed. One comes at the beginning, when the cadavers are first brought out. The other comes toward the end. “In the class, we start with the chest and then work our way to the arms and legs, then back to the chest and abdomen,” says Kulber. “The last thing we do is the head.” Up to that point, the head is covered with an opaque bag, and students take time to silently express their gratitude before the bag is removed. “As the semester goes on, little by little, the work becomes more mechanical,” explains Kulber. “But when you see the face, it all comes back: this is a person. So there’s this very emotional response.”

Because of the body shortage, and because dissection takes time, Bernd has two groups of students sharing one donor. “If the first group does the upper arm, then the next group will do the forearm,” Bernd says. “And they’ll learn from each other’s dissections.” And because the lab is open at all hours, students can return at night and on weekends to examine other cadavers. “You can see big people, small people, people of different ethnicities, people with different conditions or comorbidities and different causes of death,” Kulber says. “The lab is accessible to the entire class.”

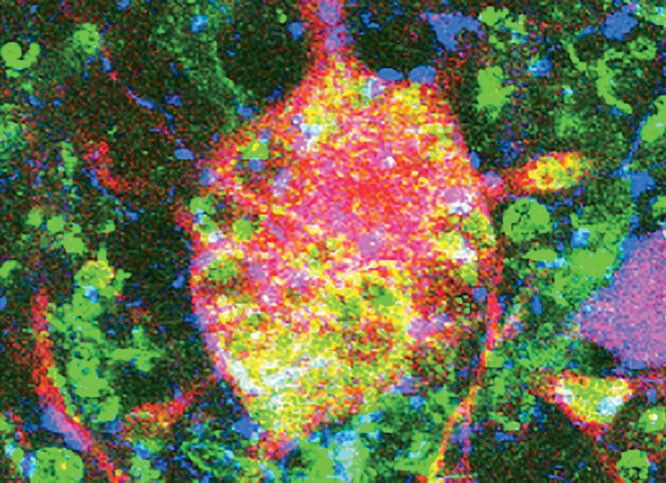

To qualify as a donor, a person must be over eighteen at the time of death and within sixty miles of the University. The body cannot be morbidly obese or emaciated and cannot have had a communicable disease or recent major surgery. Columbia will pick up the body and bring it to the morgue at CUIMC. The embalming process takes six months, since the embalming fluid must diffuse through all the body’s systems and tissues. Once the body is prepared, it becomes available for Bernd’s lab.

Donors benefit in multiple ways, says Bernd. One is knowing that, after they die, they will provide an unparalleled training opportunity for future physicians; another is saving on the cost of burial. Columbia pays for the donor’s cremation, gets the death certificate, and returns the ashes to the family. Alternatively, the ashes can be interred, for free, in a Columbia plot at Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn, the gentle-sloped, verdant resting place of Horace Greeley, Boss Tweed, Leonard Bernstein, and Jean-Michel Basquiat.

There, among the elms, a granite monument reads: In memory of those individuals whose bequeathal to Columbia University advanced medical science. IN LUMINE TUO VIDEBIMUS LUMEN.

If you are interested in donating your body to medical science, visit the webpage of Columbia's Anatomical Donor Program for instructions and contact information.

This article appears in the Fall 2024 print edition of Columbia Magazine with the title "Body of Knowledge."