The year 1965 was a banger for pop: the Beatles played the first large-venue rock concert, at Shea Stadium; the Four Tops and the Rolling Stones scored their first US number-one hits; and Bob Dylan, as the phrase goes, went electric. This last event is the subject of the 2024 film A Complete Unknown, cowritten and directed by James Mangold ’99SOA and starring Columbia dropout Timothée Chalamet as the ragamuffin songster whose genius propels him beyond the limits imposed by a world hostile to change.

The movie, which has been nominated for eight Oscars, including Best Picture, Best Director, Best Adapted Screenplay, and Best Actor, chronicles Dylan’s early-1960s evolution from a Woody-Guthrie-channeling folk singer in a newsboy cap to a post-political surrealist in dark shades who, at the 1965 Newport Folk Festival, to the shock of the folkies on the lawn, takes the stage with an electric guitar and a kickass band and attitude.

Mangold places musical angels (folksingers Joan Baez and Pete Seeger) and demons (Johnny Cash) on Dylan’s shoulders as he wrestles with his artistic urges and personal loyalties. Dylan’s decision to drive a sunburst Fender Stratocaster into the festival’s quilted heart caused a famous uproar. But to those really listening, Dylan had telegraphed his metamorphosis the year before, in his anthem “The Times They Are A-Changin.’” Dylan was ostensibly speaking of the eternal struggle of historical forces — the slow one now / will later be fast — but he might well have sung, The folk one now/ Will later be loud. Change, for Dylan, was the only constant.

Mangold peoples his movie with a gallery of famous figures who surrounded early-’60s Dylan, but one who doesn’t appear is the poet Allen Ginsberg ’48CC. While A Complete Unknown ends with the folk festival fallout, the story of Dylan ’65 did not blow away with the sea breezes at Newport. Later that year, in Northern California, Ginsberg, along with music critic and former Columbia student Ralph J. Gleason, burnished the public’s understanding of Dylan, then twenty-four, as an American artist of the first rank.

On December 3, 1965 — the day the Beatles, heavily influenced by Dylan’s example as a shape-shifting artist, released their landmark album Rubber Soul — Dylan sat down for a fifty-minute televised press conference in the studios of KQED, a public-television station in San Francisco. By then, Dylan was a superstar whose latest album, Highway 61 Revisited, featured “Like a Rolling Stone,” which some critics rank as the greatest rock song ever made. Gleason, host of the live-performance show Jazz Casual and a columnist at the San Francisco Chronicle — in 1967 he would cofound Rolling Stone magazine — recognized Dylan’s brilliance. It was Gleason who organized the Dylan press conference, inviting local reporters and a few VIPs, including Ginsberg, to attend.

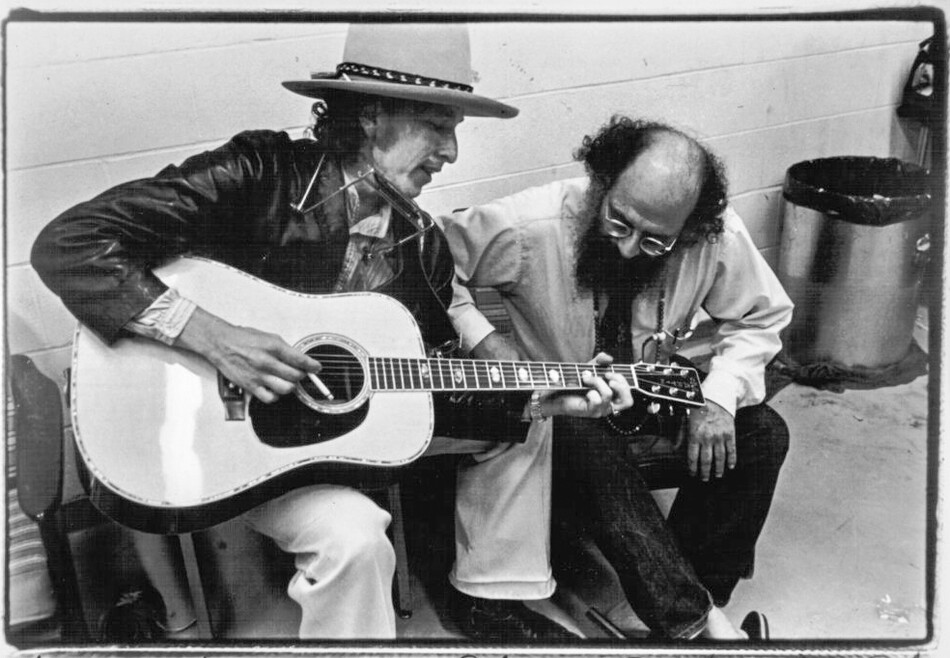

Ginsberg, whose 1956 poem “Howl” profoundly affected Dylan, had met the young troubadour in 1963, when Dylan was twenty-two and already famous for songs like “Blowin’ in the Wind,” “Girl from the North Country,” and “Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right.” Fifteen years apart, the pair bonded over poetry; Ginsberg gave Dylan books by Rimbaud and Blake. He and Dylan were both outsiders, drifters, born social critics. In the video for Dylan’s 1965 song “Subterranean Homesick Blues,” taken from D. A. Pennebaker’s documentary Don’t Look Back, Ginsberg, in a dark suit and a dark, Whitmanesque beard, stands in the background clasping a walking stick as Dylan flips cue cards with words from the song written on them. Sixty years later — and sixteen years before MTV — it’s still the hippest music video going.

In December 1965, Ginsberg made his way to the Bay Area, where Dylan was playing some shows. To the everlasting delight of Dylanologists, the poet had purchased a brand new five-hundred-dollar tape recorder and brought it along for the ride. Carrying his device around like a 1930s ethnomusicologist, Ginsberg captured Dylan’s performances as well as a tantalizing snippet of backstage talk that offers a glimpse of both personalities — the older Ginsberg a childlike asker of questions, the younger Dylan an aged, opaque oracle. When the name Marlon Brando comes up — Dylan had met him — Ginsberg, wanting to know more, asks “Does he read?” to which Dylan, with his laid-back, twangy delivery, replies, “Yeah, he reads, I guess, and he thinks about the universe, like you.”

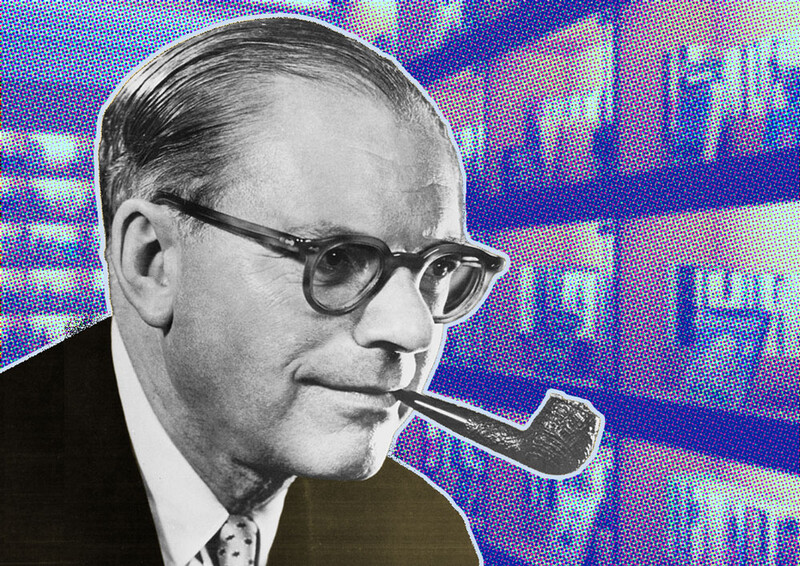

At the KQED studios, Ginsberg sat in the audience as Gleason prepared to introduce the guest of honor. With his slicked-back hair and glasses, his tweed jackets and pipe, Gleason, at forty-eight, was a pioneering jazz and rock critic, his byline appearing regularly in magazines and album liner notes. But it took Gleason a while to appreciate Dylan, as he admitted in his 1966 article “Bob Dylan: The Children’s Crusade,” in Ramparts: “When I first was exposed to his singing, I didn’t hear him, really. I only thought I did . . . Then he came to Berkeley, California, and I heard him. Really heard him. And ‘hear’ is the key word. When I met him I apologized for not digging him at first. “Y’ didn’t hear me, that’s all,’ he said softly and shook hands.”

Like any true convert, Gleason saw the light intensely, hearing in Dylan’s music a new moral language suited to the cultural moment: “Bob Dylan’s songs and lyrics changed my life because they provided a new, nonideological basis for an attack upon the evils of our society,” Gleason wrote. More than that, Dylan had “done the impossible” — had rescued poetry from the ivory tower. “He has taken poetry out to the streets and put it on the jukeboxes and brought it into the lives of everyone . . . He is the first poet of that all-American artifact, the jukebox, the first American poet to touch everyone, to hit all walks of life in this great sprawling society. The first poet of mass media, if you will.”

Now, with the TV cameras rolling, Gleason said, “Welcome to KQED's first poet press conference. Mr. Dylan is a poet. He will answer questions on everything from atomic science to riddles and rhymes. Go.”

What unfolds plays like a piece of minimalist performance art. Dylan is too skeptical of the conventions of the interview format and the motives of journalists, and too contemptuous of trite questions, to provide the pat answers that he knows would satisfy the papers. He is constitutionally incapable of playing the game, but he does try. As the reporters and students pepper him with questions about his creative process, hidden meanings in his lyrics, the terms “folk singer” and “protest singer,” his opinions on other artists, the reasons for his popularity, and more, Dylan is cagey, holding his cards close and turning them over here and there, while showing flashes of thoughtfulness, humor, blunt honesty, and heroic forbearance.

The KQED press conference, combined with Ginsberg’s field recordings of music and fan interviews that week in 1965, came in a year that saw the US bombing of North Vietnam, the assassination of Malcolm X, attacks on peaceful Civil Rights marchers in Selma, the Watts uprising, and the signing of the Voting Rights Act. By the end of it, Dylan had gone both electric and eclectic, moving further away from the topicality and social concerns of his early albums and deeper into the painterly abstractions and introspection that would pour from his 1966 double album Blonde on Blonde.

As for the elusive, enigmatic Dylan persona, which the KQED event had helped solidify, there were, of course, other sides to the artist. In 1970, guitarist David Bromberg, who had studied at Columbia in the mid-1960s — and who would record two albums with Dylan in the early ’70s — told Rolling Stone: “After hearing all those Dylan interviews and all those mysterious things you hear about him you expect the guy to be some kind of Sphinx who speaks in riddles.” That image fell away upon their first meeting. “I really enjoyed it,” Bromberg said. “We talked about music and his records, about what he wanted to do … It was really fascinating to see how straight he was.”

Ralph Gleason would remain a Dylan fan and explicator until his death in 1975 at age fifty-eight. That fall, Dylan kicked off a concert tour with a circuslike cast of musicians and friends, a vagabond community on a freewheeling bus trip across America. Ginsberg was along for the ride, and in November, in Lowell, Massachusetts, he and Dylan ducked out to Edson Cemetery, to visit the grave of Columbia dropout Jack Kerouac. It was all part of the show, the traveling carnival, which was called the Rolling Thunder Revue.

Rolling is the key word. In 2004, Rolling Stone magazine unblushingly named “Like a Rolling Stone” the greatest rock song in history. Dylan’s wheels were always burning. We see this in A Complete Unknown: a portrait of a restless, motorcycle-riding artist who can only move forward, hearts be damned. As director Mangold has said, “So many of his songs from this time are about moving on and leaving. It’s a quest for freedom.”

Ginsberg, who died in 1997, didn’t get his Hollywood moment in Mangold’s film, but he remains forever enshrined in Dylan mythology. At the end of the 2019 documentary Rolling Thunder Revue: A Bob Dylan Story by Martin Scorsese, Ginsberg, speaking of the spirit on display during that colorful concert caravan, offers words that, like Dylan’s, speak across the decades and challenge us in our own frenetic time:

“You who saw it all, or saw flashes and fragments, take from us some example, try and get yourselves together, clean up your act, find your community, pick up on some kind of redemption of your own consciousness, become more mindful of your own friends, your own work, your own meditation, your own proper art, your own beauty. Go out and make it for your own eternity.”