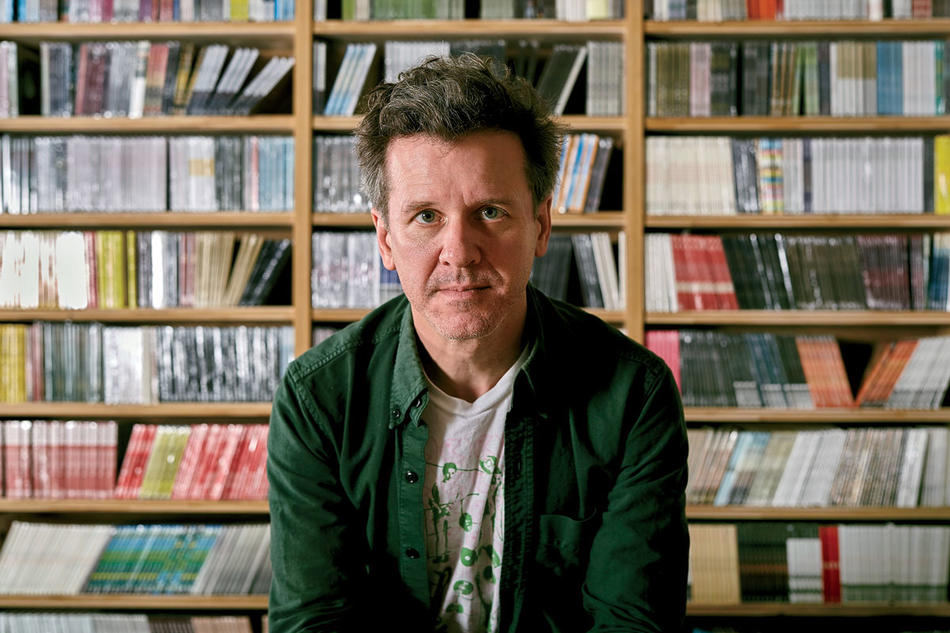

It’s a sunny afternoon in Durham, North Carolina, and at a picnic table outside a bar downtown, Mac McCaughan ’90CC is nursing a lager and fondly reminiscing about the Butthole Surfers, the legendarily anarchic Texas band. A half dozen of McCaughan’s employees, all twentysomethings, lean in and listen with amusement. But McCaughan isn’t just another boss buying a round after work. At the next table over, a middle-aged customer recognizes him and points him out to a buddy: “Well, looks like we have a bona fide rock star in our midst.”

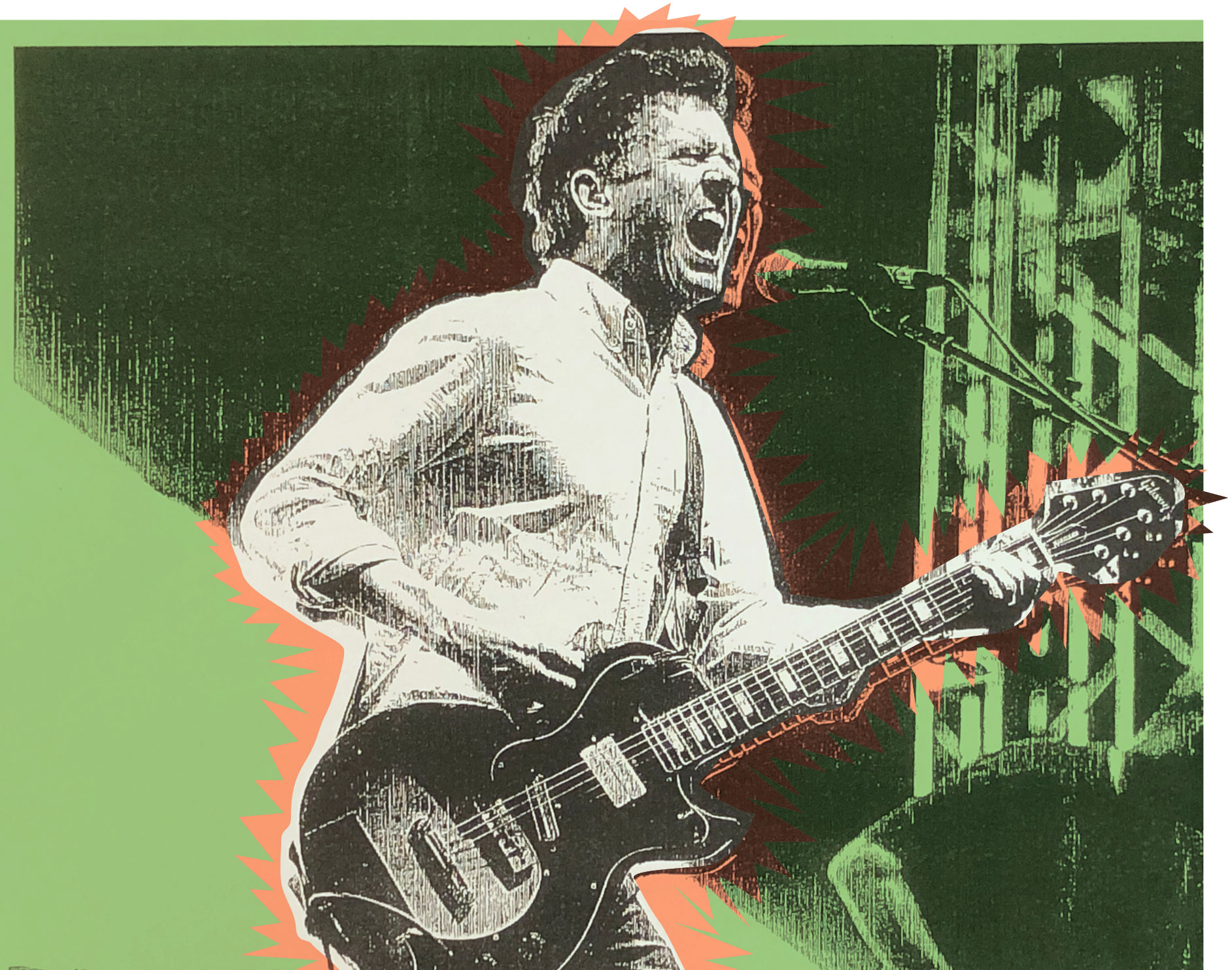

McCaughan, a slight, energetic fifty-two-year-old, is a rock star in the eyes of many. The singer, guitarist, and leader of the band Superchunk, which has released eleven albums since the late 1980s, McCaughan pioneered a brand of smart, heartfelt, and melodic punk-inspired music that has become a beloved part of the American indie scene.

But his influence extends far beyond Superchunk. Merge Records, which McCaughan cofounded with his bandmate Laura Ballance in 1989, is one of the longest-running success stories in the American independent-music industry: a small business with an outsize cultural impact. The label’s roster reads like a who’s who of indie rock: Arcade Fire, the Magnetic Fields, Neutral Milk Hotel, Wye Oak, Spoon, Bob Mould, She & Him, the Mountain Goats, and Waxahatchee, as well as a slew of other great bands.

As music writer Steven Hyden once put it, “You can’t talk about the history of American indie rock without mentioning the name Mac McCaughan.”

“The better-known Merge artists represent the most accomplished songwriters of their generation,” says Jonathan Poneman, cofounder of Seattle’s Sub Pop label, a contemporary of Merge’s.

“This is a grandiose comparison,” Poneman continues, “but think of combining the talents of Bruce Springsteen with those of his original A&R person, the legendary John Hammond, and you’d have something approximating Mac’s gifts. He’s an exuberant performer and accomplished tunesmith who has a knack for being able to discern greatness in its raw form.”

Merge is headquartered not in some sleek, anonymous office park but in a two-story yellow-brick storefront sandwiched between a furniture store and a hair salon that serves wine. Thanks to successful albums by the Magnetic Fields and Neutral Milk Hotel, McCaughan and Ballance were able to buy the building in 2001. Back then, Durham wasn’t the “it” town it is today. Now, hip restaurants, boutique hotels, and galleries are crammed into its three-quarter-square-mile downtown, and the employees of tech companies and startups occupy luxury lofts installed in the former tobacco warehouses nearby.

McCaughan’s office is packed with knickknacks and memorabilia from his thirty-year career. Sunlight flits through the trees just outside the second-story window; framed posters, show fliers, and album art cover the walls, and piles of vinyl records cover much of the floor.

“It happened so gradually that I don’t think there was any one moment where it was like, oh, now we have a record label,” McCaughan says. “We’re just doing a slightly more professional version of what we’ve always been doing.”

As a kid growing up in the seventies, McCaughan was into the popular hard rock of the time — bands like Van Halen, the Who, and AC/DC. But in 1981, when he was thirteen, his family moved from Fort Lauderdale, Florida, to Durham after his father got a job as an attorney for Duke University. When McCaughan saw a couple of hardcore-punk bands at the Duke Coffeehouse, a light went on: it was much more fun to see music up close than in vast arenas, music that was made not by otherworldly rock stars but by people who were pretty much like him.

When it came time for college, McCaughan applied to Columbia at the urging of a family friend; he remembers being eager to get to New York, a music mecca. During his freshman year, in 1985, he met Nashville transplant Laura Cantrell ’89CC. “He was this wiry-looking punk-rock kid with shaggy hair,” Cantrell recalls. “And he had more records in his room than anybody else in his dorm. He was already kind of a standout by the time I met him.”

McCaughan and Cantrell started a folk-country duo called Potter’s Field that played the old Ferris Booth Hall café, the Furnald Folk Fest, and the Postcrypt Coffeehouse, in the basement of St. Paul’s Chapel. But McCaughan was a punk rocker at heart and soon tracked down other punk fans at school. Students from cities like Boston or Washington often let their friends’ bands sleep on their dorm-room floors when they played gigs in New York, and through them, McCaughan was soon connected to the exploding mid-eighties indie underground.

McCaughan majored in history, a subject he still loves, and he says his education imparted a key lesson: “I learned how to think critically at Columbia,” he says. “I use that every day.” As an undergraduate, McCaughan also studied studio art with Nicholas Sperakis, an experience that had a different kind of influence on his career — McCaughan’s woodcuts have since adorned several Superchunk album covers, from its self-titled 1990 debut to its most recent release.

After taking a year off to play in bands in Chapel Hill, the college town a few miles down the road from Durham, McCaughan returned to Columbia in 1988 for his junior year and formed a band called Bricks with Cantrell and his friends Andrew Webster ’90CC and Josh Phillips ’91CC. Because they rehearsed in McCaughan’s apartment on West 108th Street, playing a drum set was out of the question, so for percussion they used suitcases, cardboard boxes, and plastic containers filled with rice. McCaughan set some ambitious goals for Bricks: release a seven-inch single and a cassette-only album and play CB’s Gallery downtown — all of which they achieved.

“He wanted to have his own band,” says Cantrell. “It wasn’t a question of whether he could or not — he’d already decided: I’m going to do this.” It was a key inspiration for Cantrell, who was just beginning to realize her own identity as a musician. “He just made it seem possible,” she says. Sure enough, Cantrell would become an outstanding country singer-songwriter (Bob Dylan and Elvis Costello are fans), with five albums to her credit.

Back in Chapel Hill the summer before his senior year, McCaughan started a band called Chunk. He convinced his then girlfriend Laura Ballance to play bass, though she was shy and reluctant to perform onstage. “He can persuade you to do things that you might not want to do. Some people would call that manipulative,” Ballance says with a laugh, “but with him, it’s sort of liberating.”

Thanks to a $300 loan from a friend of McCaughan’s, Chunk recorded its first single the same summer; it came out that December on the newly minted Merge Records. “It just seemed easy, so we figured why not?” says McCaughan, who knew some of the mechanics of manufacturing and distribution from working at the beloved store Schoolkids Records in Chapel Hill. “We certainly weren’t thinking it would be our job.” Soon they were releasing singles by their friends’ bands, too.

Back at Columbia for his senior year, McCaughan would take the PATH train to Hoboken to drop off Merge releases at the famous record store Pier Platters. Ballance, in her spare room in Chapel Hill, quietly did the accounting, stored the inventory, and packaged up records to be shipped, all while studying at the University of North Carolina and holding down two jobs. When they found out another band already had the name Chunk, McCaughan’s mom suggested a new name: Superchunk.

McCaughan graduated in May 1990, around the time Merge released Superchunk’s single “Slack Motherfucker,” which quickly became one of the defining anthems of nineties indie rock. It’s a joyous shout-along featuring perhaps the worst cuss word available — “I’m working / But I’m not working for you / Slack motherfucker” — but it’s also a stirring declaration of one of the indie community’s most defining qualities: diligence. “At the time it was just a declaration of annoyance with people you’re working with at Kinko’s,” McCaughan says. “But it takes on larger meaning as you go along.” The song still regularly closes out Superchunk shows.

Superchunk released its debut album in September 1990. Merge didn’t yet have the ability to properly promote, publicize, market, and distribute a twelve-inch album, so they released it through the fledgling Matador Records, soon to be an indie powerhouse itself. Raves from the internationally influential British music press and dogged touring of its galvanic live show soon made Superchunk a big favorite of the indie-rock community. By 1993, Chapel Hill’s alternative-rock scene had exploded. Entertainment Weekly speculated that Chapel Hill might be “the next Seattle.” Rolling Stone suggested that Superchunk could be “the next Nirvana.” But the band resisted the inevitable offers from major labels, opting for artistic freedom and sustainability, a philosophy both Superchunk and Merge have embraced ever since.

While touring with Superchunk, McCaughan met other bands and started to put out their albums as well. In the mid-nineties, Merge released the Magnetic Fields’ The Charm of the Highway Strip and Neutral Milk Hotel’s classic debut album On Avery Island, as well as several other indie favorites, firmly establishing it as an artist-friendly label. McCaughan talent-scouted for the label using his encyclopedically deep social network. In 1992, his Columbia friend Jonathan Marx ’90CC told him about a sprawling, motley Nashville band that he played clarinet with. The band was Lambchop, which has since recorded fifteen highly acclaimed albums, all with Merge. Fourteen years later, an old friend and Superchunk fan named Howard Bilerman told McCaughan about a Montreal band he was playing drums in. That band was Arcade Fire, which became a massive global success and provided a financial and critical windfall for Merge, especially after the band’s third album, The Suburbs, debuted at number one on the Billboard charts and went on to win three Grammy Awards.

McCaughan still keeps his ear to the ground. He buys lots of records — he discovered the London-based Afro-dance-pop band Ibibio Sound Machine because he liked their album cover. He listens to the radio (his favorite stations are Duke’s WXDU and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill’s WXYC). And he trawls the Web. But by now, the music world is also beating a path to Merge’s door. “There are a lot of different ways to find out about music, to the point that it’s a little bit overwhelming,” says McCaughan. “But frankly a lot of it is just talking to people who work here or friends you see out at a show.”

The label’s quality-control process is simple: “When people ask, ‘How do you decide which artists you want to work with?’ the answer has always been: artists that we like,” McCaughan says. “There are no criteria beyond that.”

Thanks to McCaughan’s good instincts and Ballance’s conscientious business stewardship (not to mention a little luck), the label’s reputation is so strong that fans buy records simply because they’re from Merge. Lately, though, streaming has cut into the music industry’s bottom line, and Merge is not completely immune. “Our budgets are smaller,” McCaughan acknowledges. “You look for ways to save money everywhere you can. But we’ve always been pretty good at that anyway.”

As we spoke, McCaughan was preparing to hit the road with Superchunk on the occasion of its new acoustic reworking of 1994’s Foolish album. Even after all these years, McCaughan, now married and a father of two kids (ages twelve and sixteen), is still up for the adventure of touring. And onstage, Superchunk plays at — or at least astonishingly near — the same high energy level it did when it started. “We’re playing a twenty-five-year-old’s music as fifty-one-year-olds — is that ridiculous?” says McCaughan. “But you see people who are able to do that in a way that still feels vital.”

In recent years, Superchunk has also been galvanized with new energy, particularly after the 2016 presidential election, which prompted McCaughan to dash off a batch of furious but catchy songs. They appear on the band’s latest album, the raging, politically charged What a Time to Be Alive, recorded just weeks after the inauguration. Superchunk had never made such political music before, but “in the aftermath of a would-be fascist dictator becoming president, it would be weird to write a record about anything else — for me, anyway,” says McCaughan. What a Time to Be Alive has its share of invective, but the album also addresses ways to cope with political anger. “Break the Glass,” McCaughan has said, “is a song about realizing you are in an emergency situation and trying to not lose your shit so you can respond to the ongoing disaster in a productive way.” One productive way the band responded was to send proceeds from various singles to Planned Parenthood South Atlantic, the environmental nonprofit 350.org, and the Southern Poverty Law Center.

McCaughan’s political music is part of a general philosophy about his responsibilities as an artist and a businessperson. “As cool as it is having a record label and being in a band, sometimes you think, but what are we really adding here to make things better?” says McCaughan. “Part of what we try to do is be part of the community.” And so Merge has cosponsored Durham’s Full Frame Documentary Film Festival, and McCaughan has served as a board member at Duke University’s Nasher Museum of Art. In the late 2000s, he and Ballance bought and renovated another building a few doors down from Merge to improve the block, and they’ve invested in local businesses. Whether it’s his community activities, his business, or his diverse musical projects, there’s one thing that unites all of McCaughan’s pursuits, according to his old friend Laura Cantrell.

“There’s this basic core spirit of ‘I do this because I enjoy it,’” she says. “It’s an enthusiasm and a love for music and a curiosity that I still recognize from the guy who had all the records and the crazy hair.”

Still taking his cue from those everyman hardcore bands back at the Duke Coffeehouse, McCaughan says that, whether he’s playing it or packaging it, he sees music as a job to be done diligently, unlike the self-indulgent, preening arena rockers of yore. Rock music, he says, is “something you work hard at, as opposed to something you do to get famous.” And that is Mac McCaughan: a rock star, maybe, but really just a guy who works hard at what he loves.

A Merge Records Listening Party: 5 Albums You should Know

Superchunk: Tossing Seeds (Singles 89–91) (1992)

Merge’s very first CD release contained McCaughan’s Gen-X anthem “Slack Motherfucker.”

The Magnetic Fields: 69 Love Songs (1999)

Stephin Merritt wrote this three-volume set of tunes as his interpretation of the American songbook.

Spoon: Ga Ga Ga Ga Ga (2007)

With this album, indie-rock legend Spoon finally broke into the mainstream while holding on to its experimental minimalistic pop.

Arcade Fire: The Suburbs (2010)

The Canadian-American group’s ode to the suburbs became Merge Records’ first number-one album on the Billboard charts.

She & Him: Volume Two (2010)

The duo of M. Ward and actress Zooey Deschanel banked another top-ten hit for Merge with this album, a favorite of baristas everywhere.

—Len Small

This article appears in the Winter 2019-20 print edition of Columbia Magazine with the title "Majestic Shred."