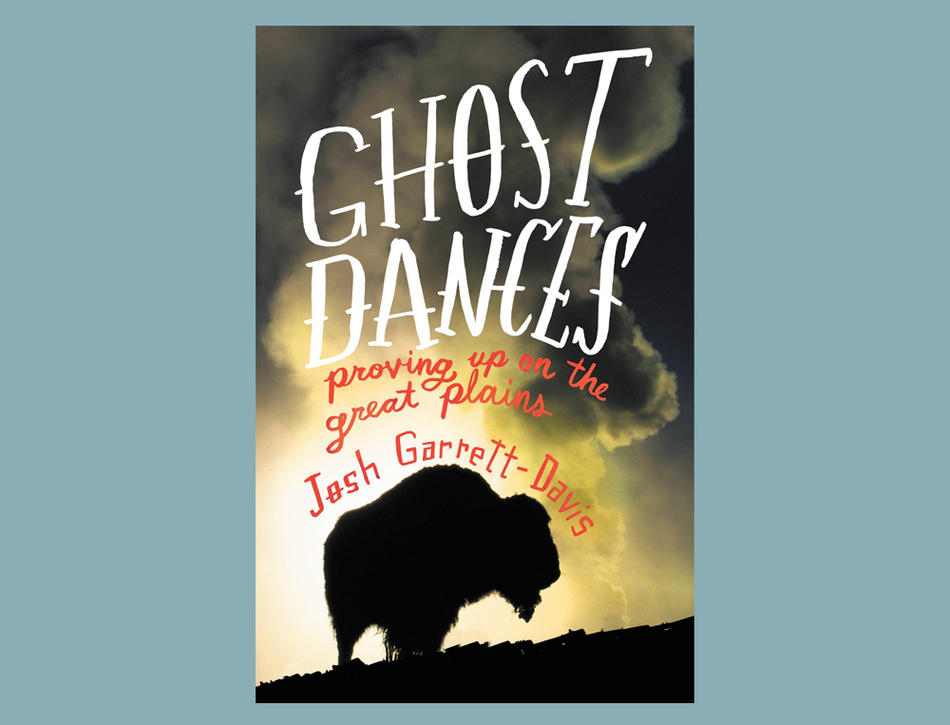

At the beginning of his memoir Ghost Dances: Proving Up on the Great Plains, Josh Garrett-Davis ’09SOA stands in front of a cage at the Bronx Zoo, staring at eleven American bison. “They’re built like woolly brown baseball players, heavyset with nimble lower legs,” he writes. “And the agitated tails sweeping city houseflies away remind me of broken windshield wipers with rubber blades whipping pointlessly.”

Garrett-Davis identifies with these animals, which inhabit an unfamiliar space, unable to return to their home on the range, and unlikely to survive there even if they could. This is the book’s point: Garrett-Davis doesn’t wish to return to South Dakota, to the home he couldn’t wait to leave, but as he looks back on the Great Plains, he sees truths about himself that have always defined him.

It’s a story he tells in an unusual way — through a mixture of history, literary criticism, personal narrative, profile, reportage, and lyricism — in a book that is essentially a collection of essays that meander like bison, loosely grouped in a herd but still standing apart as individual animals.

Things started brightly enough for Garrett-Davis’s family. “Neither of my parents was from the Plains,” he writes. His mother grew up in California, his father in Ithaca, New York. They were civil-rights activists, with a button collection up on the living-room wall screaming out against nukes and censorship. Garrett-Davis’s parents settled in Aberdeen, South Dakota, in the late 1970s, after a small courthouse wedding for which she “wore a green cotton dress, and he wore a Methodist-red corduroy sport coat,” and opened Prairie Dog Records, using family money.

They divorced when Garrett-Davis was still small, leaving him with a fractured schedule: summers and vacations with his mother and her new girlfriend in Portland, Oregon, where she moved after coming out, and the school year with his father in Pierre, South Dakota. To assuage his heartbreak and confusion, he turned his attention to skateboarding and composing earnest lyrics stockpiled for his someday-band (“Save the Elephants”: So say you’re very sorry / For taking their i-vorry). In South Dakota, which Wallace Stegner called a “flat, empty, nearly abstract” world, hiding the secret of his mother’s homosexuality is painful and isolating, but necessary, the narrator reasons, since “the first time anybody ever found out, I lost my mom.” He lost much more than just his mother, it turns out — the divorce and surrounding circumstances made him bitter and angry toward his hometown — and the narrative is devoted to trying to get it back, even if only for a split second.

Garrett-Davis supplements this family narrative with dispatches on people and places tangentially related to him, employing a bewitching and satisfying range of technique. He mixes descriptions of prairies and pioneers with those of skateboarding and punk rock and offers long explanations of the surprising things that interested him as a teen and provided him with fellowship, such as L. Frank Baum’s The Wonderful Wizard of Oz and the South Dakota governor, Bill Janklow, whom he reviled.

Some of these diversions don’t work, as when he draws hyperbolic parallels between an ownership fight over Sue the tyrannosaurus fossil, which was discovered in South Dakota and then shuttled between a number of different institutions, and his own custody battle. He is at his best when using his personal experience to illuminate some larger idea, as in the chapter that simultaneously skewers the Westboro Baptist Church (of “God Hates Fags” fame) and elevates Dakota Taylor, a gay gunslinger from a pulp paperback series. His playful spin on the writer Willa Cather is both endearing and brilliant; using her 1890 high-school graduation speech as evidence, Garrett-Davis determines that at sixteen she is “infinitely more badass” than the plains punks.

A PhD candidate in American history at Princeton, Garrett- Davis often pulls from primary sources for his pieces, including his own adolescent lyrics and local newspaper musings, letters from his mother to her marriage counselor, and timelines of the nineteenth-century buffalo slaughter. So, his prose is not academic. People “tumbleweed into South Dakota” and “splash into LA,” and hate-preacher Fred Phelps “is Walt Whitman’s evil twin, generating an overflowing word count, a commonplace book of hate-filled, exclusionary, overwrought, antique, hyperbolic, unedited provocation.” Ruth Harris, the writer’s eighty-five-year-old second cousin twice removed, is “an unshelled almond: a fibrous, sun-spotted exterior with a substantial and almost sweet heart.” His parents come across as jagged and imperfect on the page, yet his affection still rings loudest.

Early in the book, Garrett-Davis remembers a pre-divorce moment, sitting in the car with his mother: “‘The birds will use it for their nests,’ Mom would say as she let her hair out of the window of our red Datsun ... I imagined lucky robin chicks growing with a golden braid of her hair coiled around them, that rich, dark blond that mine would be if I grew it out.” The image of a shining strand of gold weaving through a nest of drab dead leaves and twigs seems to mirror Garrett-Davis’s strategy of sparking through the dry plains like a star skidding across the earth, lighting up the landscape for us to see as he blazes his path away.