In postwar Leningrad, a young Jewish girl walks with her father to the post office, carting twenty cans of sweetened condensed milk to send to her uncle, Aaron. What the girl doesn’t know is that Uncle Aaron is in a Siberian work camp, serving ten years’ hard labor for the crime of writing “counterrevolutionary” poetry while a member of the Red Army. Or that he joined the Red Army after fleeing his home in the village of Dubrovno at the age of sixteen when the Germans invaded, or that Aaron’s parents had instructed him to run and hide in the forest, while they stayed behind with his wheelchair-bound sister, rather than letting her die alone. Or that before he fled, Aaron watched the Germans shoot his parents and sister in the courtyard of their home while he hid in the attic, clutching a piece of wood until his fingers went numb.

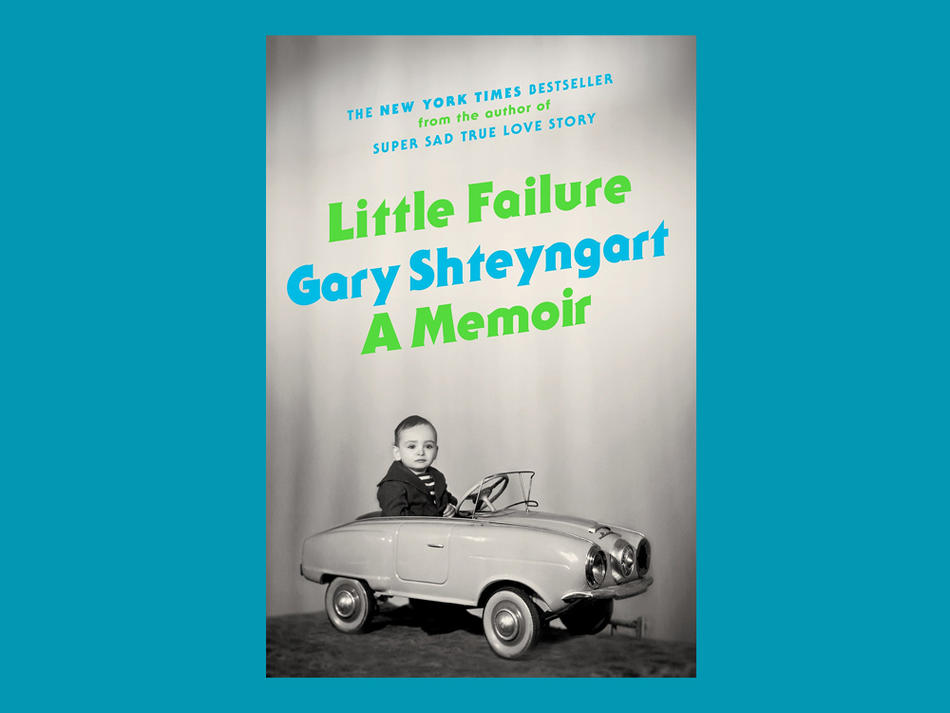

Uncle Aaron’s niece can’t know that the cans of condensed milk her father is sending to his brother-in-law serve as currency in the labor camps; that they can be exchanged to prevent rape, or torture. All she knows is that she is allowed one measly tablespoon of the treat before bedtime, while her uncle surely must drink it in great gulps. Lucky Uncle Aaron! This, Gary Shteyngart writes in his memoir Little Failure, is his mother’s first memory.

The anecdote is heartbreakingly apt for a book about how difficult it can be for children to comprehend the hardships endured by past generations, especially when families are separated by war or relocation, and the sacrifices made to improve their lives. Rather, the gaps in information, lack of context, omissions, and obfuscations often breed resentment and guilt, so that it is easier to imagine a selfish, condensed milk-glutted ancestor than to fathom the horror of your family’s actual history.

“As I march my relatives onto the pages of this book, please remember that I am also marching them towards their graves and that they will most likely meet their ends in some of the worst ways imaginable,” Shteyngart, a professor at the School of the Arts, writes. Compared to their forebears, Shteyngart’s parents had it easy. By the time Shteyngart’s mother and father bring little Gary (born Igor) back from the hospital, they own an apartment in the center of Leningrad and enjoy relative prosperity. More important, they are lucky (truly lucky, unlike Uncle Aaron) in that they receive visas to emigrate as part of Brezhnev’s plan to increase Jewish emigration in exchange for Soviet interests. As Shteyngart says, “Russia gets all the grain it needs to run; America gets all the Jews it needs to run: all in all, an excellent trade deal.” When Shteyngart is seven, the family moves to Queens, and Igor becomes Gary and begins a decades-long, systematic program of undoing all the hard work of all the Shteyngarts who came before him: in other words, becoming a spoiled American brat.

In his best-selling novels The Russian Debutante’s Handbook, Absurdistan, and Super Sad True Love Story, Shteyngart has satirized the feckless, callow, willfully underachieving “beta immigrant,” whose refusal to apply his parents’ “alpha” work ethic make him far more Americanized than his parents could ever hope to be. In life, the writer’s “deeply conservative” parents dream of their son becoming a lawyer (“what kind of profession is this, a writer?” his mother asks when he informs her of his career plans), but he thwarts their Ivy League American dreams in high school, where his own American dream is to shed every trace of his Russianness and become indistinguishable from his classmates. In 1987, this translates into Generra Hypercolor T-shirts, and California-cool outfits by Union Bay and OP: “When we walk out of Macy’s with two tightly packed bags under each arm, I feel my mother’s sacrifice far more than when she talks about what she’s left behind in Russia ... The fact that my mother just visited my dying grandmother Galya in Leningrad ... while the rest of her family, cold and hungry, waited in line for hours to score a desiccated, inedible eggplant, means much too little to me.” He soon discovers he is a terrible student and falls in with the stoner crowd, taking courses like metaphysics, where he will demonstrate tantric sex as an excuse to touch foreheads with a cute girl.

After high school, Shteyngart goes to Oberlin College, where he further disappoints his parents by studying Marxist politics and creative writing. Graduation brings misadventures in love and underemployment in Manhattan, while in Queens, the elder Shteyngarts remain defiantly unassimilated, unknowingly providing fodder for the novel their son spends the better part of a decade writing and revising. When the book is published, his father telephones to call him a mudak (“perhaps closest to the American ‘dickhead’”), while his mother howls in the background. But Gary, now in four-days-a-week psychotherapy, insists to himself, “I am not a bad son.”

Or is he? In Little Failure, Shteyngart portrays this as the essential dilemma of the immigrant child — if you fulfill your parents’ greatest wishes for you, if you become surfer-chic-clad Gary, not Russian-fur-hatted Igor, you can’t help but break their hearts. In giving meaning to the pain and suffering of your ancestors by living a better life, you exist in such security and ease that you can’t conceive of any reason your uncle would want cases of condensed milk aside from as an after-dinner treat.

This is the challenge of the memoir by the immigrant child: the writer’s American suffering (I didn’t get asked to the prom) pales so much next to his relatives’ Old World suffering (I watched my parents and sister get shot in our courtyard) that it can seem insignificant. The success of Little Failure is Shteyngart’s scrupulous examination of the chasm between his parents’ experiences and his own, and his hard-won understanding of the way his family’s murky, bloody, half-understood history informs his present. “I am small, and my father is big,” he writes. “But the Past — it is the biggest.”