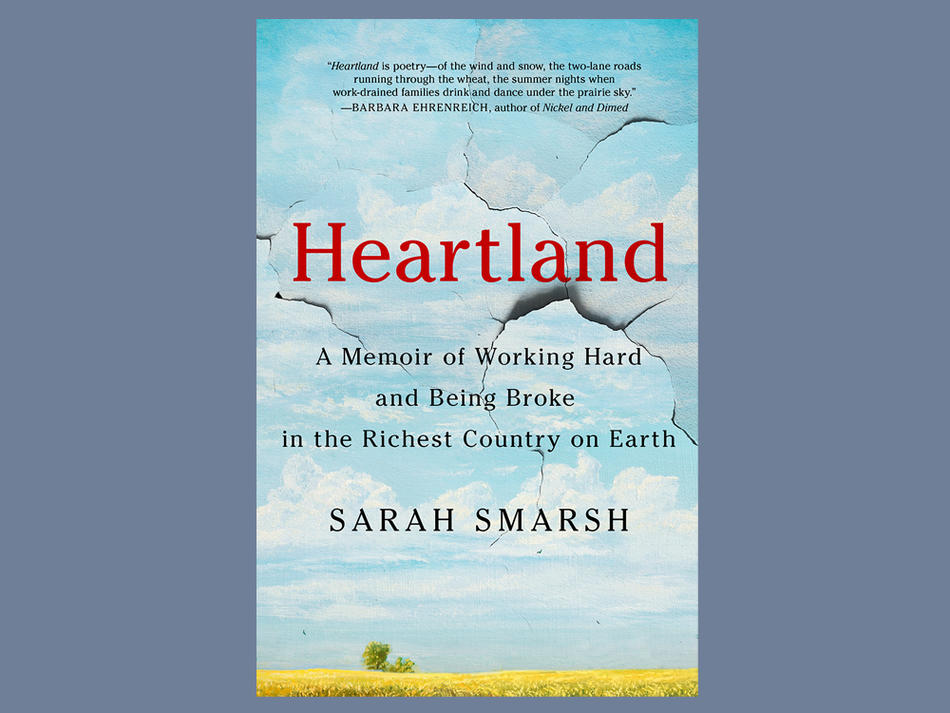

Perhaps no group has been more scrutinized over the last two years than the white working class. Countless op-eds have decried the myopia of coastal elites who, safe in their liberal bubble, fail to understand the “flyover country” that elected Donald Trump. For some, America’s cultural and political reckoning seemed to come out of nowhere. But as journalist Sarah Smarsh ’05SOA writes in her powerful, vitally relevant book Heartland, “You can go a very long time in the country without being seen.”

Smarsh was born in rural Kansas in 1980 — the dawn of a decade that would be marked by Reagan’s trickle-down economics, welfare cuts, and the early stirrings of the housing crisis. The timing of her birth, she writes, “meant that my life and the economic demise of American workers would unfold in tandem. But we couldn’t see it yet out in the Kansas fields.” Her family’s fears were more immediate: Would her grandfather’s aging farm equipment get him through the harvest? Would there be enough money to put gas in the car or pay for childcare?

Smarsh writes smartly and often poetically about the chaos that poverty creates. She was shuffled between divorced parents and grandparents, following them to wherever they could find jobs. Still, compared to previous generations, her life was relatively stable. Smarsh’s mother lived in forty-eight different places before giving birth when she was eighteen; her grandmother married seven times and seemed to traverse the entire Midwest in her quest for a better life for herself and her children.

Central to the family ethos was work — endless, often backbreaking work. Smarsh’s grandfather farmed 160 acres of land, moonlighted as a butcher, and still had to collect and sell aluminum cans to make ends meet. Her father, a skilled contractor, eventually took a job delivering cleaning solvents, which resulted in chemical poisoning and years of debilitating psychosis. To be broken physically while working was just a part of life, Smarsh writes, one exacerbated by the fact that few have access to health care. “It’s a hell of a thing to feel — to grow the food, serve the drinks, hammer the houses, and assemble the airplanes that bodies with more money eat and drink and occupy and board, while your own body can’t go to the doctor.”

If the book revolves around one question, it is this: how did Smarsh get out? After five generations of Smarshes lived in poverty with no escape route in sight, how did a member of the sixth end up with a graduate degree from Columbia, a down payment for a house, and a memoir nominated for a National Book Award? There is, of course, no single answer, but Smarsh posits some theories. She was raised in part by two supportive male role models — her father and grandfather — a rarity in a family that often fell victim to dangerous men. She avoided the trap of teen pregnancy. And yes, she was exceptionally talented and worked exceptionally hard. She was the first in her family to attend college, and when she matriculated at the University of Kansas, she did so with a merit scholarship and three jobs lined up. Without both those things, she insists, college would have been an impossibility.

Despite Smarsh’s impressive self-determination, Heartland serves as a nuanced challenge to, if not a direct rebuttal of, the conservative fetishization of personal responsibility reflected in popular books like J. D. Vance’s Hillbilly Elegy. The author is keen to show that poverty is not the result of lethargy and bad choices, and that the American dream is not necessarily attainable for anyone who works hard enough. And while Heartland is less of a political treatise than Hillbilly Elegy, politics and the consequences it has on the Smarsh clan are a powerful undercurrent to every family story.

Most members of Smarsh’s family are Republicans, which, she explains, is for them a matter of pride — even when it means voting against their best interests. “People on welfare were presumed ‘lazy,’ and for us there was no more hurtful word,” she writes. “Impoverished people, then, must do one of two things: Concede personal failure and vote for the party more inclined to assist them, or vote for the other party, whose rhetoric conveys hope that the labor of their lives is what will compensate them.” Smarsh bought into this idea as a teenager, joining the Young Republicans and campaigning for George W. Bush. It was only in her junior year of college that her perspective began to change. Studying sociology, she writes, she began to see her circumstances in a new light: “Study after study … plainly said in hard numbers that, if you are poor, you are likely to stay poor, no matter how hard you work.”

America feels more divided than ever before — politically, racially, socioeconomically — and while Smarsh doesn’t purport to know how to solve this problem, she’s a wise and eloquent guide to at least understanding its complexity. It’s also notable that Smarsh didn’t begin writing in November of 2016; rather, this book is the result of fifteen years of research into her family history. And that history, with Smarsh’s clear-eyed narration, makes obvious what many op-eds seem to have missed: Trump’s election, and the seismic political chasms that have followed, didn’t come from nowhere. It was the inevitable result of deep fault lines that have existed in America for generations.