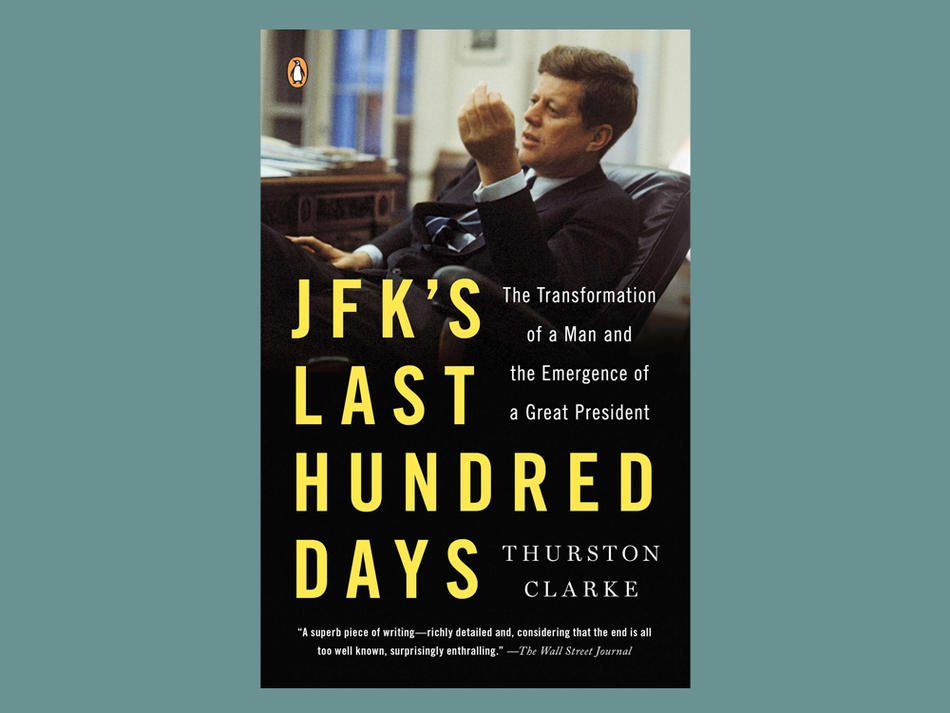

More than sixty new books have been published in the past year in anticipation of the fiftieth anniversary of the assassination of President John F. Kennedy. Is there anything new to say? Author and historian Thurston Clarke ’72BUS demonstrates there is with JFK’s Last Hundred Days: The Transformation of a Man and the Emergence of a Great President, a meticulously researched, endlessly entertaining, almost day-by-day narrative of the three months leading up to November 22, 1963.

Clarke’s book hardly belongs to the genre of unabashed hagiography published long ago by former Kennedy insiders such as Arthur Schlesinger and Ted Sorensen. Nor does Clarke gloss over the seamy side of Camelot exposed by Seymour Hersh and others. On the contrary, JFK’s womanizing is recounted in detail, down to his position after removing his back brace for a very brief roll in the hay with Marlene Dietrich. So, too, is the sordid story of his cruelty toward his wife after she gave birth to a stillborn baby girl in 1956 while the senator was on a cruise off Capri with several young women. Leaving brother Bobby to comfort Jackie and bury the child, he refused to cut short his vacation until his friend Senator George Smathers persuaded him to “haul your ass back to your wife if you want to run for president.” But in Clarke’s telling, this type of risky and thoughtless behavior came to an end with the death of his infant son Patrick in August 1963, a tragic event that transformed the womanizer into a loving husband who doted on Jackie and curtailed his compulsive philandering.

This remarkable transformation in Kennedy’s personal life was mirrored, according to Clarke, in an analogous shift in his domestic and foreign policies in the final months of his life. The hard-line cold warrior who had denounced the Eisenhower administration during the 1960 campaign for the (nonexistent) missile gap and then stared down Khrushchev during the Cuban Missile Crisis was converted into an ardent proponent of détente with Moscow. The man who authorized the Bay of Pigs invasion and then the top-secret project (code-named “Operation Mongoose” and supervised by his brother Bobby) to assassinate Fidel Castro encouraged secret contacts with the Cuban leader through intermediaries in the hopes of reestablishing normal relations with Havana. Underpinning this quest for renewed dialogue with the communist world was the fear of a nuclear Armageddon after the Cuban Missile Crisis. In his “peace speech” at American University on June 10, 1963, he unveiled his new preoccupation with achieving the first major breakthrough in nuclear-arms control, which culminated in the Limited Nuclear Test Ban Treaty, which he signed four months later. Another example of this foreign-policy turnaround was Kennedy’s decision to remove a thousand American military advisers from Vietnam by the end of 1963 and his plan to bring home most of the remaining personnel in 1964, or at least after his reelection. Clarke is absolutely convinced that, had Kennedy survived, America would have been out of Vietnam by the end of his presidency, and the Cold War a thing of the past.

In the realm of domestic policy, the conventional history portrays Kennedy as personally committed to civil rights, immigration reform, medical care for the elderly, antipoverty legislation, and other liberal initiatives, but unable or unwilling to mount an energetic campaign to convert these progressive goals into law. Lyndon Johnson is usually credited with employing his renowned skills of persuasion and his close relations with congressional leaders of both parties to pass such landmark pieces of legislation as the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Voting Rights Act, the Immigration and Nationality Act, Medicare, and the multitude of laws making up the War on Poverty. Clarke demonstrates that Kennedy himself, using his own formidable horse-trading talents to wrest concessions from partisan Republican conservatives such as Senate minority leader Everett Dirksen and House minority leader Charles Halleck, had already set in motion the legislative machinery to produce all these transformative laws after his reelection. Vice President Johnson appears throughout the book as a bitter man totally marginalized by the architects of the New Frontier. On several occasions, Kennedy, his wife, and several top aides express horror at the thought of a Johnson presidency.

Some assassination conspiracy theorists will find grist for their mill in this book. The Oliver Stone crowd will be heartened by the portrait of Kennedy’s plans to seek détente with Khrushchev and Castro, withdrawal from Vietnam, and an end to the nuclear-arms race in the face of stiff opposition from the military brass. The 1962 novel Seven Days in May, later made into a movie, described an attempted military coup in reaction to a president’s decision to sign a nuclear-arms agreement with the Soviet Union. After reading it in galley proof, JFK confessed that he had pondered the possibility of such a move by the military and named a couple of generals whom he thought “might hanker to duplicate fiction.” Proponents of the theory that Castro ordered JFK’s assassination in retaliation against the Kennedy brothers’ project to kill the Cuban leader will be dismayed by the book’s claim that both Kennedy and Castro were giving serious consideration to burying the hatchet. But Clarke’s effort to play down the Castro assassination plan and play up JFK’s turn toward moderation ignores the evidence that Operation Mongoose continued right up to the tragedy in Dallas, as Tim Weiner ’78CC, ’79JRN has shown in his Legacy of Ashes: The History of the CIA. On October 29, 1963, the CIA’s top Cuba specialist met in Paris with a prospective hit man inside Castro’s government and promised to deliver a high-powered rifle with a telescopic sight to take out the Cuban leader. Toward the end of his presidency, Johnson opined that “Kennedy was trying to get to Castro, but Castro got to him first.”