Each year tens of thousands of unaccompanied migrant children cross the southern border of the US to confront an immigration system that is at best ill-prepared and at worst unapologetically hostile. Valeria Luiselli ’15GSAS knows that system well. Her 2017 book Tell Me How It Ends: An Essay in Forty Questions detailed her experience volunteering as an interpreter in immigration court, helping lawyers determine which children might be eligible for relief.

The book was a passion project for Luiselli, a brilliant young novelist who already had a stack of literary accolades under her belt, but the nonfiction format had limits. As she writes in the opening chapter, “The children’s stories are always shuffled, stuttered, always shattered beyond the repair of a narrative order. The problem with trying to tell their story is that it has no beginning, no middle, and no end.”

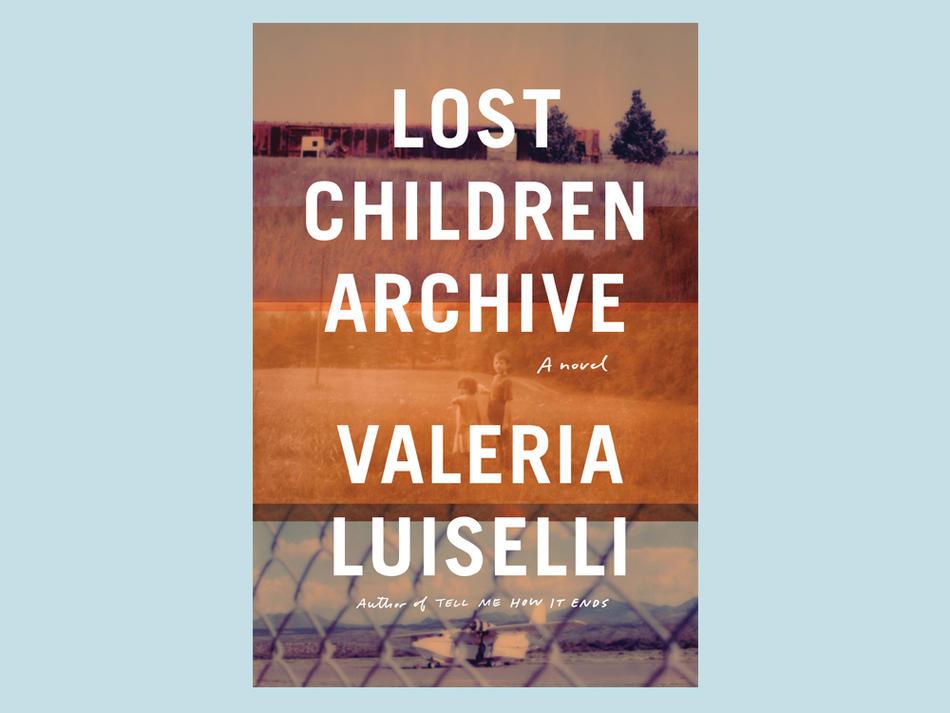

Now Lost Children Archive, Luiselli’s first work of fiction written in English, retells the stories of migrant children so that we might truly fathom their suffering and acknowledge that the roots of the immigration crisis are buried deep in our culture. The author — who was born in Mexico, grew up in South Africa, and has made her home in New York — gently prods us to look at America from a wider perspective, across generations, through an array of characters and locations, and through multiple dislocations and relocations, including her own.

But first Luiselli asks us to begin with the myriad negotiations of family life. The novel opens in a car, with a husband, wife, son, and daughter (we are given pronouns, not proper names) driving from New York City to Arizona. The couple, both Mexican, met at Columbia University, where they were working on an oral-history project. Now he wants to relocate to Arizona to research a documentary about the Apaches. Her life is in New York, where she volunteers as an interpreter and plans to record children’s stories in immigration court. Their marriage slowly floundering, they set off on the iconic American road trip hoping to find clarity.

They leave New York with boxes full of research materials: reference books, newspaper clippings, maps, photos, government reports. All are carefully organized and annotated. Their final destination is the Chiricahua Mountains in the heart of Apacheria, a place, according to the husband, “where the last free peoples on the entire American continent lived before they had to surrender to the white-eyes.”

That the couple is traveling south, in the opposite direction from the migrants, suggests this is not a summer jaunt but a form of katabasis, or descent into the underworld. This theme is underscored by the books the husband has packed for the journey: Heart of Darkness, The Cantos, The Waste Land, Lord of the Flies, and Cormac McCarthy’s The Road. The last, an audiobook, is, to the couple’s frustration, automatically cued up so that each time they turn on the player a voice intones “When he woke in the woods in the dark and the cold of the night he’d reach out to touch the child sleeping beside him.”

It’s an appropriate reminder that children are the lodestone of this novel. Not just the boy and girl in the car but the migrant children whose stories are in the news and the Apache children whose legends are retold by the husband. The wife also reads aloud from Elegies for Lost Children, a book she says is loosely based on the Children’s Crusade, in which thousands of children traveled alone across Europe in 1212 in the hope of reclaiming Jerusalem for Christendom.

As the family journeys into the desert, the stories of all these dislocated, undocumented, and brave children intertwine. The boy and girl wander off into the desert and are lost. They meet a group of migrants and spend the night with them before reuniting with their parents in Apacheria. As the drama unfolds, the author skillfully weaves together narratives that span multiple generations, perspectives, and cultures, creating a conclusion that might best be described as a spectacular singularity.

Luiselli is an erudite writer, and the novel is an interrogation of many literary texts and techniques. The elegies that the wife reads aloud each allude to literary works about voyages, but the influences are seamlessly embedded, not showy. Indeed, as the author says in her endnotes, “I’m not interested in intertextuality as an outward, performative gesture but as a method or procedure of composition.” Nevertheless, Luiselli’s wit and her references to sources as diverse as Paul Simon; Ezra Pound; Susan Sontag ’77GSAS, ’93HON; R. Murray Schafer; Laurie Anderson ’69BC, ’72SOA, ’04HON; and Sally Mann offer regular jolts of insight and delight.

Lost Children Archive gives us a deeper look into the lives of migrant children, while reminding us that this is a story that has been told before and will need to be told again. In Luiselli’s retelling she suggests that neither her first documentary approach nor her fictional approach has successfully reclaimed and revealed the children’s lives, but both texts have helped expose the darker forces that enveloped them. “That recognition and coming to terms with darkness is more valuable than all the factual knowledge we may ever accumulate,” says the narrator. “Stories don’t fix anything or save anyone but maybe make the world both more complex and more tolerable. And sometimes, just sometimes, more beautiful.”