Louisiana’s Great River Road follows the Mississippi southeast for 140 winding miles from Baton Rouge to New Orleans. Once fertile fishing ground for Native Americans, the land was portioned into long, slender lots by French settlers in the 1700s and worked by African slaves. But no greater change has marked the land than the mid-twentieth-century boom of the oil industry, which burrowed deep into the earth and built high into the air, fracturing riverbank settlements and transforming a fishing and farming region into a national petrochemical center. Today, along Cancer Alley, as some call it, one-story homes stand in the shadow of giant industrial plants. Pipelines cut through swamps and fields. In the town of Norco, a pure-white cumulus cloud fortified with volatile hydrocarbons hovers permanently above a Shell refinery.

Petrochemical America, a collaboration between the artist Richard Misrach and the landscape architect Kate Orff, surveys this land in all its imperfections. Misrach is a landscape photographer, but he belongs to a movement that attempts to reinvent the genre for the man-altered world. Between the 1970s and 1990s, Misrach documented the desert of the American West in a series called Desert Cantos. Turning away from the idealized landscapes of Ansel Adams, Misrach captured a desert transected by roads and power lines and punctuated by controlled burns and animal-burial pits, creating images that were sometimes elegant, sometimes grotesque, but always honest. Misrach’s desert is “the real desert that we mortals can actually visit,” wrote the critic Reyner Banham. “Stained and trampled, franchised and fenced, burned, flooded, grazed, mined, exploited, and laid waste. It is the desert that is truly ours, for we have made it so and must live with the consequences.”

What better exemplar of our fallen age than Cancer Alley? Here, rather than animal corpses and spent bombshells, there are toxic releases, explosions, and abandoned towns. The physical record of these traumas often presents itself as an absence: the footprints of former houses in the Morrisonville settlement, now Dow Chemical; a warning sign on a fence with nothing behind it but wildflowers and trees. It’s a subtle story, so Petrochemical America tells it twice: first through Misrach’s photographs, and second through an artistic presentation of data by Kate Orff, who as a Columbia professor integrates the earth sciences into the graduate design curriculum. The two sections are designed as complements, but they might equally be viewed as competitors. Which discipline is better equipped to capture the essential?

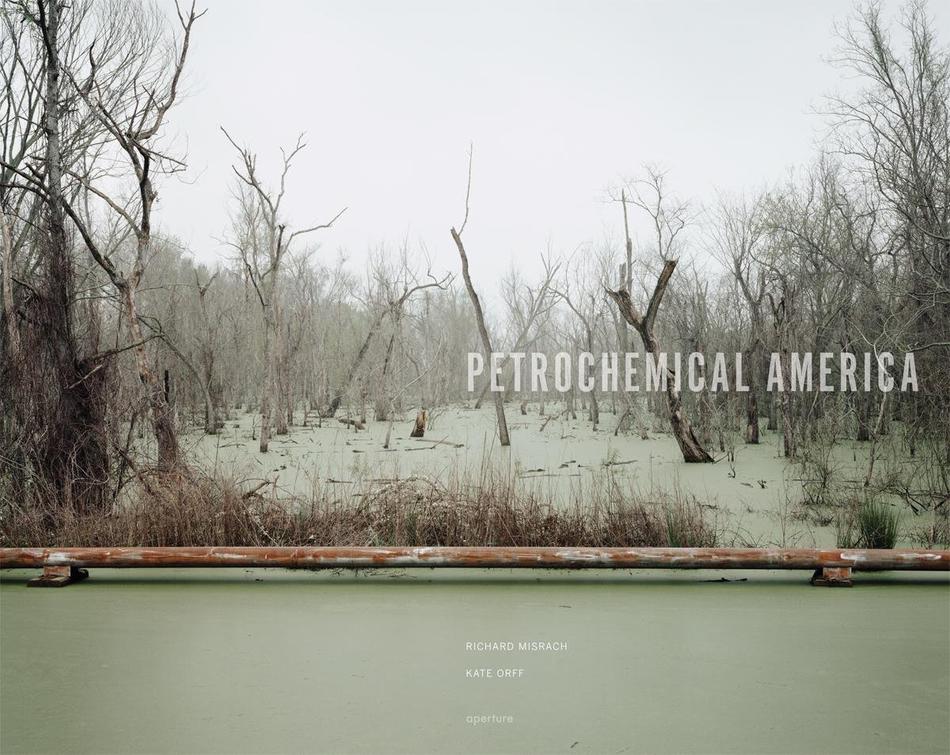

Misrach tells his story on a human scale, though his photographs are virtually unpeopled. Religious monuments sit by the side of the road, staying fast where believers have moved on. Those who have remained endure a peculiar landscape: an Archer Daniels Midland plant rises next to a modest front yard with a spindly rosebush and a small Christ statue. A swamp has turned a foamy green; sickly cypress trees protrude from the bayou. Even Misrach’s desert was more colorful than hazy Cancer Alley, which is painted from a limited spectrum of grays and greens. One is left with the impression of a place under quarantine, tranquil yet unnerving.

In her ecological atlas, Orff tries to diagnose the underlying problems, often by connecting them to large-scale systems. She traces the development of the petroleum industry, beginning with prehistoric algae deposits in the Jurassic period, and parses the effects of oil and its derivative chemicals on the earth and living creatures. In a clever design feature, Orff reproduces Misrach’s photographs in miniature and expands their boundaries to include explanatory illustrations. For example, she extends Misrach’s swamp pipeline to meet cross sections of drilling equipment on one end and chemical plants on the other. In geospatial maps, we see the pipeline stretch along the Mississippi and into the Gulf of Mexico, branching out and multiplying, with a red circle marking the site of the 2010 Deepwater Horizon explosion. Orff’s project is part academic, part political: she wants to restore people’s instinctive connection to the land and draw their attention to the ways that ordinary economic choices can ripple out to touch every part of the country.

At times, Orff’s ambition leads her to stray too far from local conditions and practicable solutions. Layers of information sprawl like suburbs, as if the atlas’s purpose were not to explain their order but to prove them unorderable. The most moving section of the atlas keeps its focus on this particular expanse of Louisiana land. Along several maps of the river, Orff charts selected incidents in the histories of affected communities. In Reveilletown, after an accident at a Georgia Gulf plant, vinyl chloride found its way into local children’s blood. In Morrisonville, fear of lawsuits led Dow Chemical to preemptively relocate the entire town in two pieces, sending one north and one south.

Amid such damage, it is occasionally shocking to notice how Misrach has looked at this compromised land and found beauty. One photograph of the water-covered batture north of Port Allen resembles a Dutch Golden Age painting, with textured sky and lush trees and shrubs reflected in the river. Images of destruction have a double pull, repelling and compelling at once, as in a sugarcane field that yields to a complex monochrome of gray sky, silver geometry, and dissipating smoke. By capturing beauty as well as hardship, Misrach implicitly makes a case for this land’s survival. “The world is as terrible as it is beautiful,” Misrach has written, “but when you look more closely, it is as beautiful as it is terrible.”