Henry Luce, the man who created Time, Life, Fortune, Sports Illustrated, and a publishing empire that both reflected and helped to define American life for much of the 20th century, waited a long time to get the biography he deserves. I labored in Luce’s vineyard for decades but never met the man, so for me Alan Brinkley’s The Publisher: Henry Luce and His American Century is a real gift.

Luce was more self-regarding than introspective, yet he might have appreciated the wisdom and generosity, if not at times the scholarly rigor, that Brinkley, Columbia’s Allan Nevins Professor of American History and provost emeritus, brings to the task.

The Luce of legend was a monomaniacal tycoon, pigheadedly pro-Republican, anti-Roosevelt, pro-business, and pro-war. Brinkley’s Luce is a vividly three-dimensional character who comes to life in ways he never did to those close enough to call themselves his colleagues: larger than life but also life-sized, domineering and insecure, dogmatic and incoherent, unbending and manipulable. He was as tough on his wives as he was on his co-workers, he did not understand himself or anyone else, and everyone around him paid a price for that, including Luce himself.

Born in 1898 to missionaries serving in China, Luce was raised to sermonize. At four years old, he would stand on a barrel in front of his father’s house in Tengchow and preach. His own true faith, however, was Americanism, which he discovered for the first time four years later — in the first decade of the “American Century” he would later so famously christen — on a long family visit to the “home” he had never known.

After a miserable boarding-school experience back in China, he was sent at 15 to Hotchkiss, a scholarship student among the elite. Ignorance of his schoolmates’ common references and sports-field rules earned him the hated nickname “Chink,” and he lived in town, away from the other boys, in a boardinghouse with fellow scholarship students. The distinction rankled, and he was determined to break through it, repeatedly being named his class’s “First Scholar,” becoming editor of the literary magazine, failing only to make the editorship of the more prestigious school newspaper because of “a boy, Hadden, who is already on the Board.” This was Briton Hadden, whom he deeply admired and whose editorial ability would daunt Luce again at Yale.

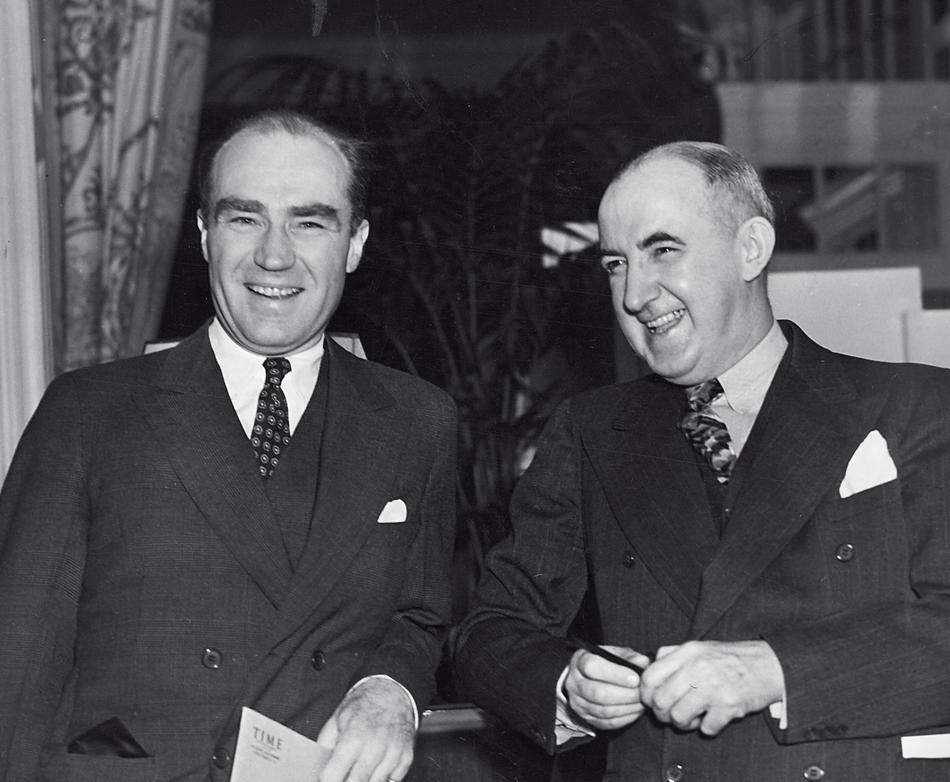

It was with Hadden that Luce founded Time in 1923, when both were 25. They planned to call the new publication Facts, a “weekly newspaper,” marketing it in contrast to the staid, objective, almost assertively bland New York Times. Luce and Hadden intuited the need for concision and summary from the popular digests of the day. The publication aimed, as Luce wrote to the woman who would become his first wife, to “serve the illiterate upper classes, the busy business man, the tired debutante, to prepare them at least once a week for a table conversation.”

Hadden took first turn as editor, and it was he who elaborated Time’s signal style. He instructed editors to avoid Latinate in favor of hard-edged Anglican English and to peg newsmakers with titles (Demagog Hitler, Teacher Scopes). He also mined his translation of the Iliad for high-baroque locutions, front-loaded sentences, and compound adjectives along the lines of “fleet-footed Achilles.” Brinkley favors us with one especially outrageous example from the introduction to a 1925 story on the Scopes trial:

The pens and tongues of contumely were arrested. Mocking mouths were shut. Even righteous protestation hushed its clamor, as when . . . a high-helmed champion is stricken by Jove’s bolt and the two snarling armies stand at sudden gaze, astonished and bereft a moment of their rancor.“But even as the magazine matured and shed some of its more egregious excesses,” notes Brinkley, “writers . . . forced readers to wade through considerable imagery before encountering any real information.”

In 1929, six years after the magazine’s launch, Hadden died of a respiratory illness complicated by exhaustion and heavy drinking. Although Luce always styled himself editor in chief, he named a new editor for Time after Hadden’s passing and turned his energy to a new business-magazine idea. (Though Hadden had belittled the idea, Luce told the board that Hadden had been all for it.) In 1930, he launched Fortune into the teeth of the Great Depression: an oversized, luxurious anachronism with photographs by Margaret Bourke-White, art by Rockwell Kent 1904CC and Diego Rivera, and text by Dwight Macdonald, James Agee, Archibald MacLeish — hardly the sort of people to toe what became his anti-Roosevelt line.

But Luce always called himself a liberal, and his politics were anything but consistent. From the beginning, Luce and his magazines were progressive on race. Early on he espoused “welfare capitalism.” In one memo he described Fortune’s editorial mission this way: “Goddamn you Mrs. Richbitch. We won’t have you chittering archly and snobbishly about Bethlehem Common [stock] unless you damn well have a look at the open hearths and slagpiles — yes, and the workers’ houses of Bethlehem, Pa.” In fact, the early issues of the magazine featured investigative stories and progressive politics of such bite that advertisers grew nervous.

Six years after Fortune came the instantly and almost ruinously popular Life (ad rates were fixed for a year while circulation ballooned into the millions, burying Time Inc. in unmet printing and distribution costs). Life’s luminous coverage of World War II (Time coined the term) was followed by its pitch-perfect theme song to the ’50s, with photo spreads of idealized scenes of America’s serene suburbs. Life’s Thanksgiving 1954 issue asked: “How can one feel thankful for too much?” and its July 4 issue the next year proclaimed, “Nobody is Mad with Nobody.” Life’s faithful adherence to such an amiable and popular view of that decade has undermined a better understanding of the ’50s to this day.

A prolific writer of caustic memos, Luce earned a reputation for strict, even ham-handed control over his magazines, but among Brinkley’s most interesting findings is how many times Luce allowed himself to lose the fights he picked with his editors. When he wanted Time to name General Douglas MacArthur as Man of the Year in 1951, the editors declined, naming Iran’s new premier Mohammad Mossadegh instead. They fought Luce over his growing distaste for FDR and the New Deal, over his rapturous support for Wendell Wilkie and Dwight Eisenhower, and over his tepid endorsement of Richard Nixon over JFK. They abandoned him on China and, decisively, on Vietnam. The wonder is not so much that he tangled with his staff so frequently as that he did not fire more of them for insubordination. In this fact, Brinkley suggests, lies the key to Luce’s greatness as a publisher.

Given Time Inc.’s editorial and financial success, Luce can hardly be faulted for feeling that he and his magazines were somehow kissed by fate. In retrospect, nothing seems quite so quintessentially Lucean as all the meetings and memos in which he agonized over the “purpose” of his magazines — the endless “rethinking” of their ambitions and the role they played, or could play, in creating the American Century. One of his memos was actually titled, “The Reorganization of the World.”

His real genius, though, lay in his instincts about his magazines and his people. He hired wonderful writers, photographers, and editors, with whom he struggled mightily and often with pain when, against his stated principles, he let them have their way. When there was a business problem, he assumed it lay in the quality of the magazines, and he worked to make them better.

Luce died in 1967, and he would not recognize the company today. Time Inc. magazines still do fine journalism — People’s recent coverage of Haiti, for just one example — but Life is a photo collection, Time is no longer a news primer (there are apps for that), and Fortune and Sports Illustrated, like most other magazines, are to some extent beset. In their day, though, the Time Inc. magazines defined greatness in magazine publishing, and Brinkley has given us the enviable model of a man of his moment who knew what to do with it, even if he did not always know what it was he knew.

I have to confess to feeling an involuntary shock when I first noted the title on the cover of Brinkley’s book. The Publisher is arguably appropriate, but it is not the title Luce ever wanted. The one he took was that of editor, but that, too, is misleading.

As Brinkley persuasively concludes, Luce was not an original thinker; his magazines portrayed the world more than they shaped it, as much as he may have wished otherwise; he continually worked to cast himself and his company in the role of America’s prophet laureate; and he presided over a great deal of the best magazine journalism ever produced.

He was, in short, someone who could have appeared in Time under two of its most characteristic early rubrics, “Point with Pride” and “View with Alarm.” Though he attributed his success to intellect rather than intuition, he was, for all of that, a man with the music of magazines deep in his lonesome soul.