Few dared be out during the seventies. Try it and likely you’d lose your job, your family, and maybe your life. Even in New Orleans — where anything goes, supposedly — staying on the down low was best. But at least there was the Up Stairs Lounge: the ramshackle gay bar on the outskirts of the French Quarter, where “friends and lovers could exhale and be themselves,” writes journalist Robert W. Fieseler ’13JRN, author of the exquisitely and exhaustively reported Tinderbox. “It was just the kind of neighborhood place that seemed to welcome all.”

Opening in 1970 on Halloween night with a jukebox and dancing license, the Up Stairs had “kind of a sweetness.” Hustling and drugs were forbidden. Impromptu sing-alongs commenced next to the baby grand. A supersized copy of the notorious Burt Reynolds Cosmopolitan centerfold smirked from a wall. Red swathed the interior — red wallpaper, red carpet, red barstools. But the gaudy decor belied a discreet exterior, says Fieseler: “The place was somewhat concealed, and only those in the know entered.” That included the polyester-clad gay doctors, lawyers, and politicians who climbed the saloon’s creaky steps to commingle with the drag queens and blue-collars. Surely a safe space — or so they thought.

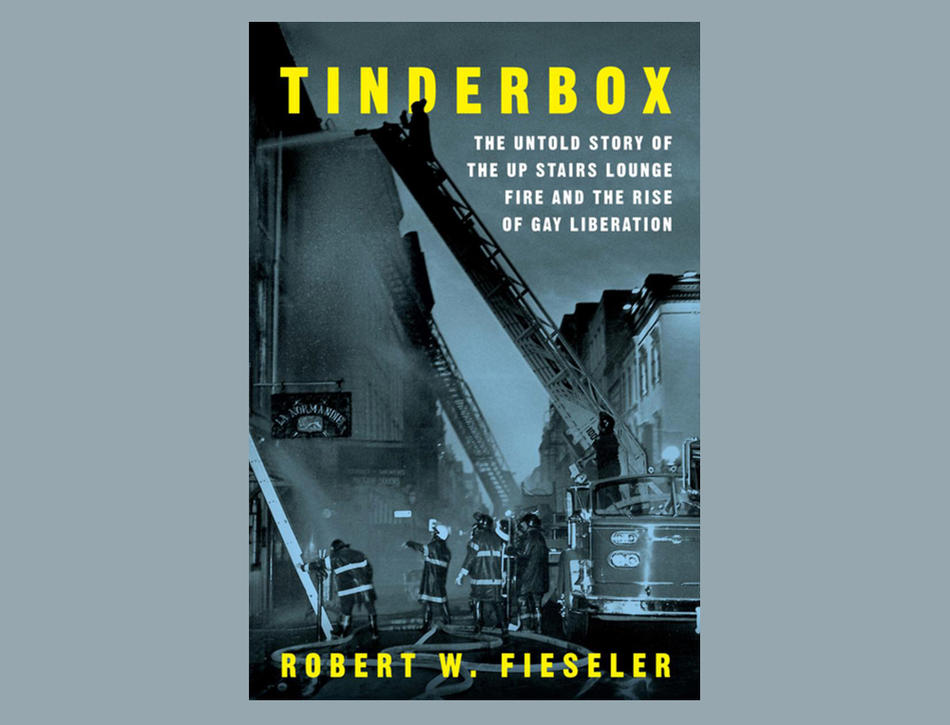

Until the Sunday night of June 24, 1973: “Fire flew down the length of the bar in a backdraft that resounded like a cannon,” Fieseler writes. Thirty-two died. Arson was the cause. The author’s chronicle of the carnage is unsparing. “The floor became embers beneath them, burning through the soles of shoes,” he recounts. “Ceiling tiles dripped molten Styrofoam on their heads like napalm.” The only way to identify some of the bodies was by their jewelry and hotel-room keys. Eight of the survivors spoke to Fieseler; they recollect escaping a “holocaust” with only seconds to spare. Some found the hand of the lounge’s heroic bartender, Buddy Rasmussen, who led more than twenty patrons to safety. Others somehow stumbled out, badly burned: “Blinking, they screamed and gagged, alive with ashen faces, their clothing scorched and hair vanished.” A reader will feel the heat.

The fire made front-page news all over the world. (Almost none of the papers would print the word “homosexual.”) But locals hardly seemed to care about the catastrophe. A joke about “flaming queens” tore through the city. Recalled one shopkeeper in the quarter: “Most of the people were glad … the feeling was they had it coming.” The gay community, whipped and disorganized, remained silent.

Investigators, discovering the lounge was torched, soon found a suspect — a sexually conflicted drifter. He was never prosecuted. Instead, political expediency was honored, sensibilities were served; like the bodies of the dead, the trauma was buried. Within days, New Orleans was ready to move on. “Mass amnesia,” says Fieseler. “Like a veil dropped over the memory of a city.”

Nearly five decades would pass before Fieseler reclaimed the story. “As a queer person, I was hooked and obsessed,” he says. Tinderbox, his first book, took four years to write and research. Until he started, he had never spent a day in New Orleans. Now he and his husband are moving there.

Nearly a half century after the fire, much has changed. Gay marriage — unthinkable in 1973 — is law. Yet Louisiana does not offer job protections to LGBTQ citizens; a homophobic boss can fire gay employees just because they’re gay. Even small progress, Tinderbox reports, is often achingly slow. In 2003 — after thirty years of struggle — the New Orleans LGBTQ community, no longer defeated and silent, succeeded in placing a bronze plaque at the site of the Up Stairs Lounge tragedy. The City of New Orleans cooperated. There for all to see are the thirty-two names of those who died in the fire. Passersby may leave flowers; many do. The fight is hardly over. But amidst the scent of bitter ashes, hope blossoms.