Jennifer Steil’s parents, friends, and bartender were understandably baffled when, in September 2006, she left New York to become editor in chief of the English-language newspaper the Yemen Observer. At the time, she was in her late 30s and had been working as a senior editor at The Week magazine. By her own admission, she had spent years entangled in a series of hopeless love affairs and was not opposed to drink and sexy dresses. Why on earth would she choose to live in a poor, strict Muslim country in the Middle East where alcohol was prohibited, women wore the hijab, and the threat of terrorism was ever present? At her going-away party, Tommy the bartender summed up the general mood: “The next time I see you, you will be in a kidnap video.”

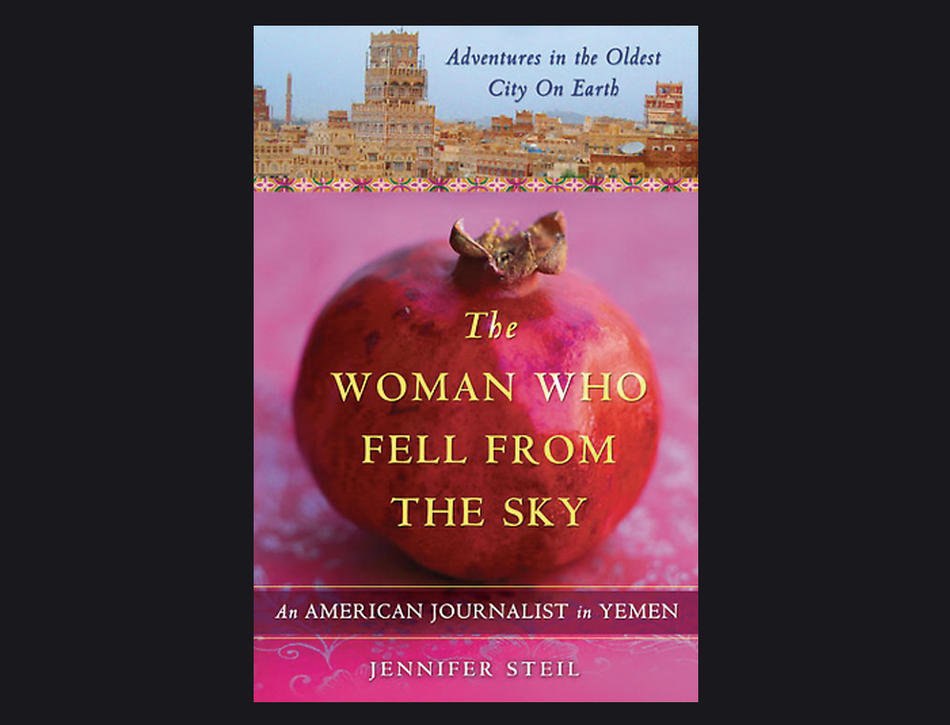

Judging from her lively memoir, The Woman Who Fell from the Sky, Steil ’97JRN has never been one to worry too much about making a decision. Instead, having been to the Yemeni capital Sanaa for all of three weeks earlier in the year to run a training course for journalists, she breezily dismisses her parents’ concern and packs her bags, driven by a liberal zeal to make the world a better place. “I imagined writing pieces that would trigger policy changes, reduce terrorism, and alter the role of women in society,” she writes. “Oppressed peoples all over the world would beg me to come and transform their own press!”

It didn’t quite turn out like that, of course, and Steil’s writing is at its best when relating the jarring disconnect between her idealism and the frustrations of life in an ancient city. On her arrival, Steil is confronted with writers who can barely speak English, let alone understand the rigors of journalistic clarity, fact-checking, and objectivity. Her efforts to reform the paper are hampered by a proprietor who cares more about maintaining friendships with government cronies than cultivating an independent press. “It is difficult to pin down exact deadlines,” she writes, because when she asks a reporter if he can file his story by 1 p.m., “the answer is ‘Insha’allah. If God is willing.’” The main reason for missed deadlines, aside from a casual attitude toward work, is that her male reporters spend their days chewing qat, a locally grown plant with amphetamine-like effects.

Steil’s dedication and professional experience do manage to improve the Observer, however. The writing gets tighter and more accurate, reporters cover some real stories, and the paper even comes out on time.

Still, there are the tiresome daily problems for an unveiled Western woman: constant catcalls in the street, masturbating taxi drivers, and Yemeni men who fail to grasp that Steil’s unmarried, childless status does not automatically make her either a whore or a freak of nature. Invited over to eat by her elderly neighbor Mohammed, Steil recalls: “They ask if I have a husband and I lie. They ask if I have children and I tell the truth. ‘But maybe I would like some,’ I say. This sends Mohammed’s wife into fits of laughter. ‘Maybe!’ she says. ‘Maybe!’”

Steil recounts such episodes with humor and verve, but perhaps her greatest asset is her ability to interweave the personal with the political. She uses her experience as a springboard into an examination of Yemeni culture and history, and as a result the prose is never dry, the narrative always engaging. She is particularly good on the treatment of women as second-class citizens: As a Westerner, Steil is at first impatient with their acquiescence to a highly patriarchal society. At the same time she finds that her female reporters are by far the most reliable and devoted members of staff. “This is partly because the women don’t have the same sense of entitlement that the men do,” she writes. “They feel fortunate to have the opportunity to work.” While the women generally have less training than the men — and can’t even go to university, take a job, or stay out after dark without permission of a male relative — “they have the requisite will. . . . They arrive promptly and do not disappear for three or four hours during lunch.”

Interestingly, Steil’s perceptive analysis of other people’s behavior does not seem to extend to her own. When, toward the end of the book, she falls in love with the British ambassador Tim Torlot, the discovery that he is already married barely seems to give her pause for thought. Instead, she is mesmerized by “the sparkliest blue eyes I have ever seen” and kisses him “full on the lips” at a party. His wife is given only the briefest of mentions, despite Steil’s frequently decrying the unfairness of Yemeni men taking second spouses. When her friend Zhura — who is about to become a second wife — points out the parallels in their respective situations, Steil replies blithely, “Tim isn’t keeping his first wife.”

It is unfortunate that The Woman Who Fell from the Sky ends on this note. To conclude the book in the grip of an adulterous love affair seems to demean the rest of Steil’s writing, shoehorning it into the traditional narrative arc of chick lit when it actually has much more to offer. Steil has produced an affectionate, insightful, and enlightening pen-portrait of modern-day Yemen. It did not need the addition of those sparkling blue eyes.