Most of us trace our roots to other places, remembered or forgotten or never known. For the first generation, adrift in a new language and culture, obliged to abandon old occupations and family ties, mere economic survival can be difficult. Immigrant children have their own set of challenges. They pay the wages of adaptation and assimilation, struggling with being outsiders while trying to fit in.

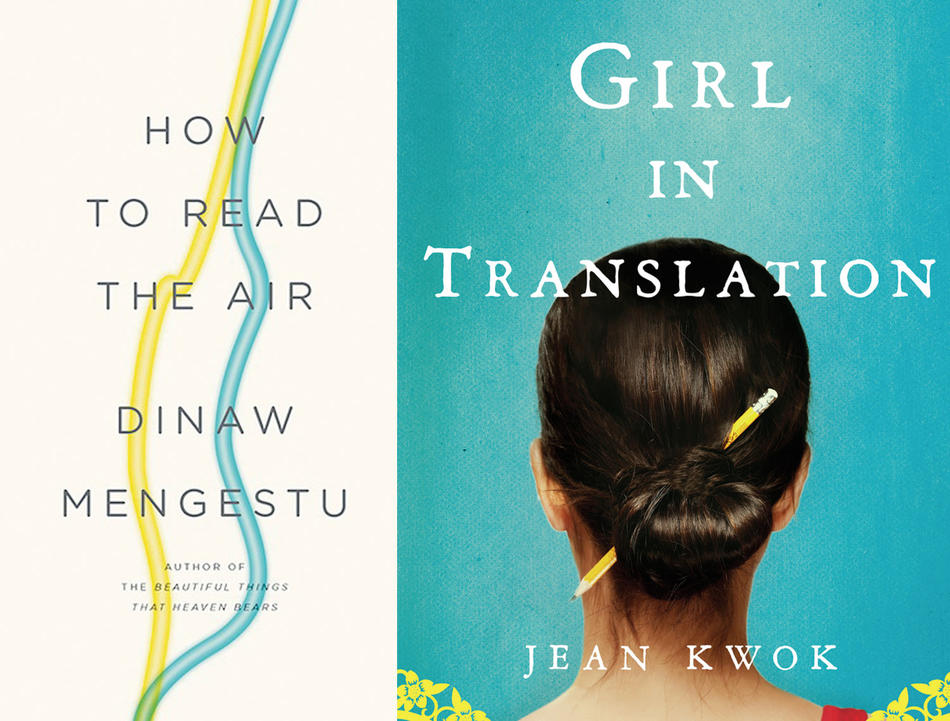

Two recent novels by Columbia graduates — How to Read the Air by Dinaw Mengestu ’05SOA, and Girl in Translation by Jean Kwok ’97SOA — tackle this subject with originality and grace. Both works read like memoirs, with narrator-protagonists intent on sloughing off the past and entering the American mainstream.

To start with, that means achieving both an advanced education and career success — enough to justify parental sacrifice, or redeem parental indifference. Mengestu’s American-born protagonist, Jonas Woldemariam, the son of Ethiopian immigrants, aspires to finish a doctorate in modern English literature — if only he can get around to it. Meanwhile, he dabbles in fiction of various sorts. (Mengestu himself was born in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, in 1978, came to the United States two years later with his family, settled in the Midwest, received degrees from Georgetown and Columbia, and now lives in Paris.)

How to Read the Air is a chronicle of family dysfunction, reminding us that time and distance won’t blot out a legacy of violence. We are what our history has made us, even in the land that promised to wipe everything clean. We may pretend otherwise, and the pretense may be healing. “There is nothing so easily remade as our definitions of ourselves,” Jonas declares at one point. This masterly novel turns out to be a metaliterary commentary on the art of fiction and how we invent our lives and identities — like our stories — from scraps of hope and memory.

Mengestu’s justly lauded debut, The Beautiful Things That Heaven Bears (2007), was a sensitive exploration of the lives of African immigrants marooned in Washington, D.C. How to Read the Air is even more ambitious, embracing two generations and a wide swath of the country.

Employing flashbacks and flash-forwards, Mengestu juggles four principal story lines without sacrificing momentum. First is the tale, part true (in this fictive world) and part imagined (even more than fiction normally is), of how Jonas’s father, Yosef, made the arduous journey from his native Ethiopia, via Sudan, to America, curled up in a box. His journey recalls the feat of Henry “Box” Brown, the Virginia slave who, in 1849, escaped by mailing himself north in a crate to Philadelphia abolitionists.

The second narrative involves Yosef’s disastrous vacation trip from Peoria, Illinois, to Nashville, Tennessee, with his secretly pregnant wife, Mariam. The two were married in Ethiopia, shortly before he emigrated. After three years, she has rejoined him in the United States, a move she quickly realizes was a mistake. The book’s title refers in part to the charged air of violence that exists between them.

At the heart of the book is Jonas’s own crumbling marriage to a lawyer named Angela, also the daughter of African immigrants. Angela, more focused and financially responsible than Jonas, alternately enjoys and recoils at his abundant capacity for invention. Jonas’s first job, in a refugee resettlement center, involves embroidering refugee accounts of distress and persecution to make them seem more pitiable. It turns out that writing fiction suits him. So does relating it. In his next job, a part-time teaching position at a high school he calls only “the academy,” he spends several class hours concocting his father’s immigration saga.

Finally, there is Jonas’s visit to his mother at a housing complex two hours from Boston, and his retracing of his parents’ fateful trip — the culmination of his attempt to piece together the narrative of their lives.

As Jonas and Angela struggle to connect emotionally and to make ends meet in their tiny New York basement apartment, Jonas decides that another fiction can only help: He informs her that he has been offered a permanent position at the academy, and that he will at last be starting graduate school. That audacious lie, quickly exposed, is a blow from which their marriage cannot recover. But the novel’s denouement is softened by its redemptive embrace of the past. “We do persist, whether we care to or not, with all our flaws and glory . . . ,” Mengestu writes. “If there is one thing that has to be true, it’s this.”

Kwok’s often mesmerizing Girl in Translation is a simpler, more linear novel, blessed with a vivid central character and tremendous narrative drive. Like Kwok, 11-year-old Kimberly is an emigrant from Hong Kong — and, unlike Jonas, she is passionately driven to succeed.

She is also more embattled by external forces, facing not just a language barrier but a decrepit Brooklyn apartment crawling with roaches and mice, and an endlessly spiteful aunt who exacts every dime she can from Kim and her mother. We shiver with mother and child in that unheated apartment, where the cold was “like the way your skin feels after it’s been slapped,” where it “crept down your throat, under your toes and between your fingers.” We feel the blistering heat in the garment sweatshop where both Kim and her mother work, as waves of steam roll off the presses.

School offers an escape route from poverty and isolation.

At first, Kim’s academic efforts are hindered by her struggles with the language, as well as hostility from classmates and teachers. Her widowed mother, who was a violinist and music teacher in Hong Kong, is supportive but astonishingly helpless, and Kim assumes a quasiparental role. She also finds, in classmate Annette, a loyal, loving friend, and Kim’s exceptional math and science talents quickly become apparent. A full scholarship vaults her into private school, and her dreams begin to seem within reach — until romantic complications threaten to drive her off course.

Kwok’s reading of the segregated, insecure immigrant life is powerfully authentic. She does less well with her love story, though, which shades into melodrama. Kim falls for a fellow garment worker, who is sweet, smart, handsome, and crazy for her. But, having sacrificed an education to earn money, he seems confined to the working class she is determined to leave behind. Can this possibly end well?

“Sometimes,” Kim’s mother tells her, “our fate is different from the one we imagined for ourselves.” But for Kim, brains are destiny, and the burden of marriage is a potential distraction. “I had an obligation to my ma and myself,” she explains. “I couldn’t have changed who I was. I wish I could have.” Life won’t be easy for her, but she, too, will persist, in all her flaws and glory.