Brad Meltzer, Bestselling Author, Shares His Secret to Mega-Success

There’s a small square logo in the upper left-hand corner of each of Brad Meltzer’s popular children’s books with a big message: “Ordinary People Change the World.” The adage befits the series, a group of charmingly illustrated biographies of inspirational figures, from Amelia Earhart to Jackie Robinson to Mister Rogers. But Meltzer ’96LAW argues that the motto is a through line in his entire body of work. It could just as easily be applied to his thrillers, which regularly top the New York Times bestseller list and often feature ordinary folks who manage to uncover some of the government’s darkest secrets and save America from total collapse. Or to his nonfiction, a series that focuses on little-known conspiracies that might have changed the course of history, had it not been for the heroic interventions of people we’ve likely never heard of. It might even apply to Meltzer himself, once a scrappy kid from Brooklyn, today someone who has not only met every president since George H. W. Bush but was even recruited by the Department of Homeland Security to help combat terrorism.

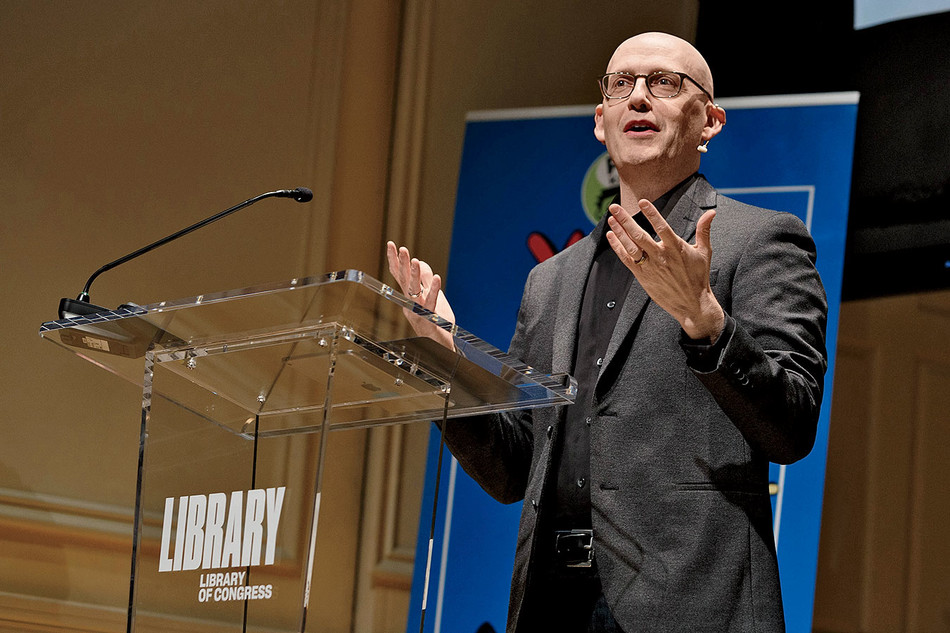

Meltzer, an enormously successful author across a variety of genres, is one of the only writers to hit the bestseller lists in fiction, nonfiction, children’s literature, advice, and comic books. He has hosted two television shows and created another, and his TED talks on storytelling have garnered over three hundred thousand views. With audiences both vast and influential, Meltzer has tried to use that power for good — supporting dozens of charities, making a lifelong commitment to child literacy, and even going to extraordinary lengths to do noble deeds, like recovering a long-lost artifact from Ground Zero a decade after 9/11. If ordinary people change the world, Brad Meltzer tries hard every day to be one of them.

Meltzer grew up in Sheepshead Bay, Brooklyn — “the part that hasn’t been gentrified yet” — in a house with no books. “The only thing in our house with words was the National Enquirer,” he says. His father was in the “schmatte” business — Yiddish for ladies’ housedresses. To make a little extra money, he also worked in a greeting-card store under Penn Station. Sometimes he would come home from the store with comic books, which is what Meltzer remembers reading.

“But my grandmother had this magical thing called a library card,” Meltzer says, “and the librarian took me to the children’s section and told me that it was my section. All these beautiful shelves of books, and they were all for me. That was the day my world got bigger.”

Meltzer remembers falling in love with Judy Blume — he read Superfudge first and then Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret, an unlikely pick for a preteen boy. “At first, I just wanted to know how girls worked,” he says. “But that book ended up teaching me one of the greatest lessons in life — that you have to love yourself for who you are.” Then the librarian gave him Agatha Christie’s The Murder at the Vicarage, which ended up sparking a lifelong love of mysteries and thrillers.

“I didn’t know what a vicarage was. In fact, I still don’t. All I cared about was that there was a dead body on those pages. I wanted to know everything about it. How did it get there? Why? And most importantly … whodunit?” Meltzer says. “I’ve been asking that question ever since. Agatha Christie taught me that stories aren’t about what did happen. They’re about what could happen.”

When Meltzer’s father was thirty-nine years old, he lost his job, which was catastrophic for a family already skating on thin ice. Unable to keep their house, the family relocated from Brooklyn to Florida, where Meltzer’s grandmother had previously moved. The whole family squeezed into her one-bedroom apartment. “He billed it as this big adventure, this big game,” Meltzer says. “It wasn’t a game. We genuinely lost everything. We were one step away from homelessness.”

Meltzer was about to start high school, and his grandmother used a fake address to get him into a school in a better neighborhood. There a teacher ended up changing the trajectory of his life. “There was an English teacher named Sheila Spicer who told me for the first time that I could write. She honestly was the first person that ever told me that I was good at something,” Meltzer says. “A decade later, when my first novel was published, I came back and handed her a copy of the book and told her that it was because of her.”

Not only did Spicer believe in Meltzer, boosting his confidence when no one else had, but she also paved the way for him academically, setting him on the honors track that would prepare him to go on to a rigorous university. “I honestly thought that after you graduated high school, you just got a job. That’s what life was,” Meltzer says. “College wasn’t even a dream before her.”

Meltzer’s family only had enough money for him to submit one college application, and he says he picked the University of Michigan on a whim. “I think it was literally that I liked the color of their T-shirts,” he says. “But then I was committed. It felt like something I was doing not just for me but for my whole family. If I hadn’t gotten in, I would have just tried again the next year.” But Meltzer did get in, and he says that studying history as an undergraduate helped him blossom intellectually and gave him a foundation for the thorough research that he’s still known for today.

Meltzer graduated in 1992 and moved to Boston, where a mentor had promised him a corporate job, which would help him put a dent in his student loans. But the week he arrived, he learned that the mentor had left the company and the job had fallen through. With time to kill and what he thought was a good idea bouncing around his head, Meltzer figured he’d use the year to write a novel. “I thought, everyone has one good story in them,” he says. “Maybe this was mine.”

While he worked on the novel, he decided to apply to Columbia Law School, where his high-school girlfriend, now wife, Cori Flam Meltzer ’95LAW, had just started her first year. He was called in for an interview with James Milligan ’83TC, then dean of admissions. “All I talked about was books and movies. I thought I blew it,” Meltzer says. “But I quickly learned that Columbia isn’t just a factory feeding into law firms. They want people who think a little differently. And I got in.”

The next fall, as Meltzer began law school, he was putting the finishing touches on his first novel, Fraternity. “So of course as soon as I got to campus, I started looking for free legal advice,” he says. Meltzer asked faculty member Jane Ginsburg for help copyrighting his manuscript, which “I like to say is a little like asking the head of the Treasury Department for help doing your taxes,” he says. She became a trusted mentor, offering him useful advice as well as introducing him to contacts who eventually helped him get his first literary agent.

He says that his professors were universally supportive of his literary career, even on the most practical level. When Meltzer was ready to start sending out his five-hundred-page manuscript to agents, he didn’t have the money to make the photocopies. So dean of students Marcia Sells ’81BC, ’84LAW made the copies for him.

Despite all Meltzer’s efforts, his first novel never found a publisher — he ended up getting twenty-four rejection letters. “Which is actually pretty impressive, because there were only twenty publishers,” Meltzer says. “So that meant some publishers actually rejected it twice.” But the week that the twenty-fourth rejection letter arrived in the mail, Meltzer was sitting in David Leebron’s torts class and found that his mind was wandering. “I wrote down the words ‘Supreme Court’ and ‘clerk’ and ‘book idea,’” he says.

Intrigued by the idea of Supreme Court clerks — young people who suddenly have a tremendous amount of power, he started writing a second novel, The Tenth Justice, about a Supreme Court clerk fresh out of Yale who is tricked into leaking the outcome of a not-yet- released decision. Meltzer says he learned everything he needed to know to write that book in the first year of law school. “It’s sort of a crash course in all the fundamentals — contracts, torts, civil procedure, property, constitutional law, criminal law, research, and writing.”

He still needed time to actually write the book, and for that he took a one-credit independent study. “I worked harder for that one credit than I did for any other class in law school,” Meltzer says. But he also needed something else — the same thing that Sheila Spicer had given him in high school: encouragement. That he got from Kellis Parker — Columbia’s first Black law professor — who taught a class called Jazz and the Law. Meltzer picked him to be his adviser for the independent study, thinking someone arts-minded might be sympathetic to a student writing a novel. After reading the manuscript, Parker wrote one comment back to Meltzer: “Keep going, baby.”

“It just takes one person saying yes,” Meltzer says. “I’ll forever be thankful to Kellis Parker.”

That yes turned into more affirmations — this time from agents and editors. By the time Meltzer entered his second year, he had a two-book deal. When he graduated from Columbia in 1996, the New York Times ran a story on him on the front of the Metro section with the headline “Presumed Best Seller.” “Honestly, it must have been a slow news day,” he says.

Meltzer accepted a job offer with a big law firm and took the bar exam. “If my father taught me one thing,” he says, “it’s that life can implode at any moment.” But he never actually started work. The firm gave him a year off to write the second novel of his two-book deal, and in the meantime, his publishing career took an unexpected turn. His editor, a rising star with some hit clients on his roster, left the publishing house for a new job with a rival publisher. Meltzer still had a contract with the first house but worried that his book would get buried there. He took a big risk and left his contract to follow his original editor. The decision paid off in spades. The Tenth Justice, Meltzer’s first published book, became a bestseller. “And that’s when the silliness began,” he says.

Meltzer never did end up practicing law. Instead he went on to write twelve more thrillers, all of which hit the New York Times bestseller list, most making it to number one. His fast-paced, conspiracy-packed, intricately plotted page-turners blend together several of Meltzer’s intellectual interests: history, the law, and good storytelling. “I think what makes a great story is the details,” Meltzer says. To get those details right, he does obsessive research, particularly around the workings of the government. “Before 9/11, I literally had the blueprints of the bunkers under the White House. Now things are a little more tight-lipped.”

In fact, shortly after September 11, 2001, Meltzer got a call that seemed to come straight out of one of his books. The Department of Homeland Security was forming a working group with the CIA, the FBI, psychologists, and even fiction writers to brainstorm new ways that enemies might attack the United States. “They were looking for out-of-the-box thinkers,” Meltzer says. “I figured if they were bringing me in, they must be getting pretty desperate.”

Meltzer later got research help from some unlikely sources: former presidents George H. W. Bush and Bill Clinton, both of whom had previously reached out to express admiration for his work. His relationship with the Bush family blossomed. Meltzer worked with Barbara Bush on a number of literacy events, and when Meltzer was gathering background information for his 2011 novel The Inner Circle, Bush gave him a copy of the letter that he had left for his successor, Bill Clinton. Bush would eventually become a close friend, so close that he asked Meltzer to read to him when he was ill at the end of his life.

When Meltzer was doing research for his Culper Ring series, whose premise is that a secret spy ring founded by George Washington still operates today, a footnote about the first president caught his eye. “I’m still a Columbia Law nerd at heart — trained to read all the footnotes,” he says. The note alluded to a thwarted conspiracy to kill Washington. Meltzer decided to dig a little deeper and learned that, during the Revolutionary War, Washington was surrounded by an elite group of soldiers who served as his bodyguards — but some of those guards had ulterior motives.

Meltzer considered using the idea for one of his novels. But he wondered if, in this case, the truth might be more compelling. He tabled the idea for many years, but he eventually teamed up with a longtime research partner, Josh Mensch ’06JRN, and wrote The First Conspiracy, his first nonfiction book. The book, published in 2019, was a critical and commercial hit, and Meltzer and Mensch followed it with two more history books: The Lincoln Conspiracy, about a failed plot to kill Lincoln to prevent him from taking office, and The Nazi Conspiracy, about a plan to kill the leaders of the Allied nations. “To me, a good story is a good story,” Meltzer says. “I’ve spent a lot of my career focused on fiction, but in the end I don’t think the genre matters that much, as long as you have a compelling narrative arc.”

Meltzer has branched out into many other genres over his career. A lifelong lover of comic books, he has worked with DC Comics to write several of their series, including the best-selling Justice League of America, for which he won an Eisner Award. “If I could tell ten-year-old Brad that this is what I get to do for a living, I think he’d die of happiness,” he says.

Now Meltzer is using his deep knowledge of the comics world to chart new territory in the industry. In October 2023, he announced the launch of Ghost Machine, a comic-book media company he founded together with eight other writers and artists, in which authors will maintain ownership of their characters.

The concept is innovative in an industry that has long been frustrating to the creative talent, who, because they don’t own the copyright to their own characters, often don’t financially benefit from the ultimate success of their ideas. The company’s first series, Geiger: Ground Zero, came out in November, followed by Ghost Machine, whose sixty-four-page first issue is scheduled to be published this month. Both are supernatural stories with overlapping universes, set partially in one of Meltzer’s favorite places: the White House.

Meltzer has also been successful in television: he created a drama series on the WB called Jack & Bobby about two teen brothers, one of whom would grow up to be president; and he hosted two shows on the History Channel. In one, Decoded, Meltzer investigated historical mysteries, such as the curious death of Lincoln’s assassin, John Wilkes Booth, and the cryptic symbol at the base of the Statue of Liberty. In the other, Brad Meltzer’s Lost History, he partnered with archivists from the Library of Congress to find lost and stolen historical artifacts.

On the very first episode of Lost History, Meltzer’s team sought to find a flag that was raised over Ground Zero in the aftermath of 9/11 — made iconic by a prominent photograph — but that went missing twenty-four hours later. During the episode, Meltzer talked with obvious emotion about a friend he had lost on that harrowing day. He offered a reward of $10,000 for the flag. “I said, I want this back for my friend Michelle,” Meltzer says. “Four days after the episode aired, a man walked into a fire station in Washington State and said he had the flag.”

It took nearly a year to authenticate it. The man who had returned it was a collector who said he hadn’t realized what he had. But, he claimed, it was Meltzer’s impassioned appeal that made him stop to consider his collection. On the fifteenth anniversary of 9/11, Meltzer unveiled the flag at the National September 11 Memorial & Museum, where it is now on display.

“The two History Channel shows were very much in my wheelhouse,” Meltzer says. “But it was an exciting challenge to work in a different medium, to be able to reach people in a new way.”

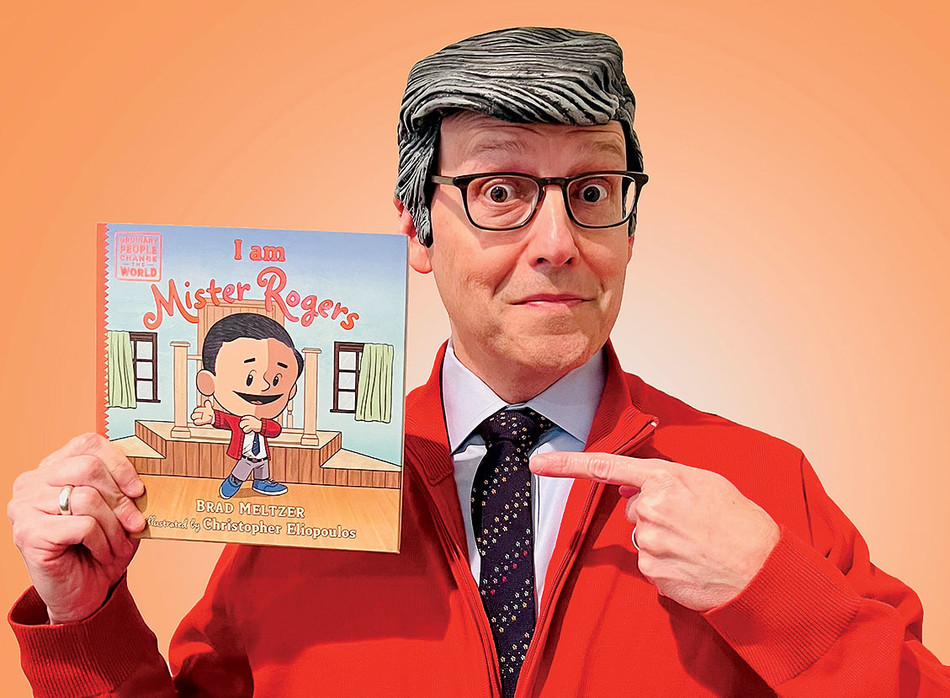

Meltzer is perhaps proudest of his children’s book series, which just celebrated its ten-year anniversary. Meltzer has three kids, and when they were younger he found himself thinking about their future role models. “I wanted to teach them that being famous is different than being a hero,” he says. He couldn’t find examples of books geared toward kids in preschool up to early elementary school that introduced real inspirational figures through compelling stories and warm, inviting illustrations. So he decided to write the books himself. He thought that his middle child, Lila, would really fall for aviator Amelia Earhart, so he started with her. From there it was a matter of finding the right illustrator. “Any cartoonist can do cute,” Meltzer says. “What we needed was heart.”

Meltzer approached Christopher Eliopoulos, an illustrator he knew from working in comics, and together they began the Ordinary People Change the World series. Meltzer says that when he chooses his subjects, he looks for people who would interest his three kids. “One of my sons loves animals, so I did Jane Goodall for him,” Meltzer says. “My other son is a sports fan, so I did Jackie Robinson.” During the 2016 presidential campaign, he noticed that two books were selling out over and over again: Martin Luther King Jr. and George Washington. “We were seeing what was happening in the world and trying to find an antidote for it,” Meltzer says.

This January, Meltzer will publish his thirty-second children’s book, which is also one of the most personal for him: I Am Ruth Bader Ginsburg. The book tells the life story of the pioneering Supreme Court justice, who was also a fellow Columbia Law alum and mother of Meltzer’s cherished mentor Jane Ginsburg.

“Getting a chance to revisit Justice Ginsburg’s story, and particularly her time at Columbia, was emotional for me,” Meltzer says. “Just as Columbia Law School helped shape her, it shaped me.”

In recent years, Meltzer and his wife have decided to pass that gift along to future generations. They endowed a scholarship at Columbia Law School in the name of James Milligan, the late dean of admissions who took a chance on an applicant who was a little bit different. “Without him, I never would have had the opportunity that I did,” Meltzer says. “We hope that we’re able to open the same kind of doors for someone else.”

Meltzer does most of his writing from the attic of his home in Hollywood, Florida, where he’s lived with his family since graduating from law school. A steep spiral staircase separates him from the rest of world, which feels apt for a mystery writer obsessed with secrets and conspiracies. But a figure of Charlie Brown, a set of Lego comic-book heroes, and framed Superman prints quickly betray his playful side.

There are stacks of fan mail on his cluttered desk, though Meltzer says he only keeps the letters from children, as a reminder of who he’s working for. And he says he always has copies of his first two published books close by, as a reminder of how far he’s come. Those touchstones are important, because when Meltzer isn’t writing, he’s working on causes that put books in children’s hands. He volunteers his time with numerous organizations, particularly in his home state of Florida, that help foster child literacy, a cause he’s long been passionate about.

“I think that reading is a superpower,” Meltzer says. “It’s the best gift that we can give our kids.”

That gift has gotten complicated lately, because of politically motivated book bans in libraries and school systems. Two of Meltzer’s books — I Am Billie Jean King and I Am Martin Luther King, Jr. — were banned by a Florida school board last year, a decision he was able to successfully appeal. “It honestly felt like a miracle,” he says. “Both Fox News and MSNBC agreed with us, which may be the first time that’s ever happened.”

Meltzer is now working with PEN America on some larger efforts to combat the banning of books across America. “If you’re on the side of book banning, you’re on the wrong side of history,” says Meltzer.

Meltzer says that he owes his success to all the people who fostered his love of reading — his father, who brought home his first comics; the librarian who showed him the stacks of children’s books; his high-school English teacher who encouraged him to write. He hopes he can have the same kind of influence.

“I believe in the power of stories,” he says. “They can take you anywhere.”