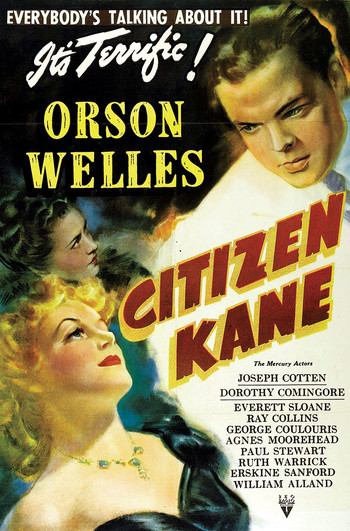

Once a month, Ben Mankiewicz ’92JRN, the primetime host of Turner Classic Movies (TCM), leaves his home in Santa Monica, where he lives with his wife and ten-year-old daughter, and travels to TCM studios in Atlanta to record a series of two-minute introductions for upcoming movies. Wearing a suit and tie, with a neatly pressed handkerchief peeking from his breast pocket, Ben stands in a stage-set living room and invites viewers to pull up a chair. “Good evening, everyone, and welcome to Turner Classic Movies,” he says. “I’m Ben Mankiewicz.” Looking directly at the camera, he’ll give the backstory of Double Indemnity or Singin’ in the Rain or Casablanca, or perhaps a movie written by his grandfather, Herman Mankiewicz 1917CC, or made by his great-uncle, Joseph Mankiewicz ’28CC. Between them, brothers Herman and Joe worked on more than two hundred movies, from silent comedies to postwar dramas to the film that some critics call the greatest ever made, Citizen Kane. That a present-day Mankiewicz should be flame-keeper of Hollywood’s Golden Age has a thematic unity that his screenwriting forebears might have appreciated.

Ben was hired in 2003, and almost twenty years, hundreds of intros, and one isolating pandemic later, he is nothing less than America’s movie therapist, a reliable, reassuring presence who connects people to the past and to each other. Whether educating his audience, interviewing motion-picture royalty (Faye Dunaway, Steven Spielberg, Warren Beatty), or hosting film festivals, he brings a wry, intelligent, movie-loving energy to his TCM work that quickly reels you in.

“There’s no channel like it,” he says of the venerable pay-TV network, which is owned by Warner Bros. Discovery and shows movies from the full catalogs of Warner Bros. and MGM, as well as films licensed from other companies. “No one ever says ‘I love CBS’ or ‘I love Showtime.’ But they say ‘I love TCM.’ This is a network that creates a visceral feeling of community.”

Despite his pedigree, Ben, fifty-five, was not raised on the movies. Politics and baseball were the kitchen-table topics. His father, Frank Mankiewicz ’48JRN, was a political strategist and media insider, and Ben grew up in a suburb of Washington, far from any movieland dazzle. He knew that his grandfather had written Citizen Kane, but he didn’t see the film until he was in his teens.

In college he began paying closer attention to Mankiewicz movies, as well as to Mankiewicz history. And when he enrolled at Columbia to study broadcast journalism in 1991, establishing the fourth generation of Columbia Mankiewiczes, he stepped foot on the soil that fostered the family saga — a blockbuster epic of fathers and sons, brothers and booze, ribaldry and rivalry, politics and prose; a narrative where little, if anything, has gone according to script.

That script begins with the man in the portrait that hangs in a room in Ben’s house: a bare-pated, mustachioed patriarch whose eyes seem to gaze out in eternal disapproval. Born in 1872 in Berlin, Franz Mankiewicz 1915GSAS, known as “Pop,” was a German-Jewish immigrant who came to New York in the early 1890s, moved to Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, to edit a German-language newspaper, then returned with his family to Manhattan, where he taught German and French at Stuyvesant High School. Beloved by his students and feared at home, he was, by all accounts, a demanding, short-fused disciplinarian who imposed his will on sons Herman and Joe.

Herman took the brunt of it. If he scored 97 percent on a test, the story goes, Pop would want to know what happened to the other three points. He insisted on a total effort from his sons. Eleven years apart, the brothers were prodigies and both entered Columbia at age fifteen. Herman went first, in 1913 — and what a kick in the pants it must have been when Pop enrolled at Columbia the same year to get his master’s in education. Still, Herman — “Mank” to his pals — thrived on Morningside Heights. A philosophy major known for his sharp wit, coarse manners, nose-thumbing irreverence, hard drinking, heavy gambling, and literary aplomb, Herman was a proud member of the Boar’s Head Society, a literary club founded by English professor and Great Books advocate John Erskine 1900CC, 1903GSAS, 1929HON, who would be an important mentor to both Mankiewicz brothers.

Herman wrote for the Jester and had his own humor column in the Spectator, called “The Off-Hour,” in which he dished up lofty pearls of campus gossip, mischievous advice, and doggerel. He also wrote the book and lyrics for the 1916 Varsity Show, a rambunctious comedy called The Peace Pirates, which satirized Henry Ford’s 1915 effort to send a ship of peace activists to wartime Europe. Herman was highly popular (“People loved him,” Orson Welles would later say of the Hollywood-era Herman. “Loved him. That terrible vulnerability. That terrible wreck”), and his campus clique included Oscar Hammerstein II 1916CC, 1954HON (lyricist and librettist of Oklahoma! and Carousel), Lorenz “Larry” Hart (lyricist of “My Funny Valentine,” “Manhattan,” and “Isn’t It Romantic?”), and Howard Dietz, a lyricist who, as a publicist for Goldwyn Pictures — later MGM — adopted a lion as the studio’s symbol, inspired by Columbia’s maned mascot.

The US entered the war in April 1917, and Herman joined the Marines, arriving in France a week before the November 1918 armistice. By then he had lost many Columbia friends in combat. He got a job in Paris with the American Red Cross news service and followed the flawed peace negotiations at Versailles. In a letter home, he wrote, “When I look at the outline of the Peace Treaty and then think of Freddy Gudebrod [1915CC] and Joyce Kilmer [1908CC] and Jeff Healy [1918CC, captain of the Columbia football team] and Herb Buermeyer [1916CC] and the hundred others that I knew and of the millions of other Freddy Gudebrods and Kilmers and Healys and Buermeyers that I didn’t know, my blood boils.”

Herman came home in 1920, married Sara Aaronson, moved for two years to Berlin (where Pop had family and where Herman was a correspondent for the Chicago Tribune), then returned to New York. In short order, he became a theater reporter for the New York Times, worked on plays with George S. Kaufman and Marc Connelly, drew blood at the Algonquin Round Table (that famed Midtown lunch club for the rapier-witted), and, in 1925, became the first regular drama critic at a new smart-set magazine called the New Yorker.

Brilliant, brash, “the funniest man in New York” according to Algonquin confrere Alexander Woollcott, Herman had amassed such gambling debts that in 1926, when producer Walter Wanger at Paramount offered him a juicy two-year contract to write title cards for the (still silent) motion pictures, Herman gathered Sara and their two boys, Don and Frank, and headed to Hollywood. Franz was not pleased: he found movies frivolous and a waste of Herman’s mind — a judgment that would haunt his older son for the rest of his life.

“Pop was a tremendously industrious, brilliant, vital man,” Herman once said. “A father like that could make you very ambitious or very despairing. You could end up by saying, ‘Stick it, I’ll never live up to that and I’m not going to try.’ That’s what happened eventually with me.”

Joe Mankiewicz entered Columbia in 1925. He was, in Herman’s words, “fiercely ambitious,” and given his gifts it was natural for Joe to slide into his big brother’s outsized footsteps. Joe idolized Herman. He, too, wrote for the Jester and the Spectator. A premed major who switched to liberal arts, Joe played baseball, acted in a German-language play, worked on the yearbook, and led a campaign for more toilets in Hamilton Hall (“Columbia needs a bowl, not a stadium” was his slogan). He didn’t write a Varsity Show, but he did contribute to a campus literary magazine called Varsity. And — like Herman — he found a mentor in Professor John Erskine.

Along with Pop, who by then was a professor at City College, Erskine steered Joe toward a career in academia and theater. And Joe, aware of Pop’s disappointment over Herman’s surrender to the seductions of the movie business, vowed to stick to the books. He graduated at nineteen and, like his brother, he went to Berlin, where he worked as a reporter and, through Herman, got a job translating title cards for German movies.

Herman, meanwhile, was living high in Hollywood. His opinion of the place is evident in his famous 1926 telegram to Ben Hecht, then a playwright in Chicago: millions are to be grabbed out here and your only competition is idiots. don’t let this get around.

And in 1929, when he got word that Joe, who had returned to New York, needed money, Herman sent another fateful dispatch: for christ sake come out to Hollywood.

Though Joe had made promises to Pop and Erskine, Herman was like a giant magnet, and Joe hopped a train to California. Herman met him at the station, and that night they went to a party at the home of Jesse Lasky, head of production at Paramount.

“I stood there like a kid who had been locked into a candy store,” Joe recalled in a 1986 interview. “My God, there was Clara Bow! Olga Baclanova, Kay Francis, Gary Cooper, George Bancroft … these women, stars, they all were there. I couldn’t take it, and I saw a familiar back. A familiar back, broad, tall. And it turned around. And it was Professor John Erskine. Who else in the world could have shown up and made me feel guiltier? Horror. I had given my oath to this man. And he looked at me and he said, ‘Joe?’ And I said, kind of sickly, ‘Hello, Professor Erskine.’ He said, ‘Joe, what are you doing here?’ I said, ‘Well, what are you doing, Professor Erskine?’ He said, I’m writing at Warner Brothers, where are you?’”

Joe could not have invented a more delicious twist. Erskine had published a best-selling novel, The Private Life of Helen of Troy, that he was adapting into a screenplay. Later, Joe would say of the encounter, “At the moment, an illusion shattered that I don’t think I’ve ever recovered from.”

But that didn’t stop him from going all in. Soon he was writing scripts for W. C. Fields and the child star Jackie Cooper. As recounted by Herman’s grandson Nick Davis in his dual biography of the brothers titled Competing with Idiots, Joe, the up-and-comer, was proud of Herman’s big-shot stature in the town. But as Joe’s own status grew, so did Herman’s condescension toward him — which only intensified Joe’s resolve. Where Herman was passionate and reckless, Joe was cautious and calculating: his was the ambition of the understudy.

Herman had always been a fish out of water in Hollywood, and he diligently maintained his New York ties. A parade of clever New Yorkers passed through his house in Beverly Hills (where movie talk was verboten), and he even served as president of the Southern California chapter of Columbia’s alumni club. When the Lions football team, which had gone 7–1 in 1933, was invited to play Stanford in the Rose Bowl for the national championship, Herman decided that Coach Lou Little and the team should be welcomed at the train station by a real lion. And so he gathered his sons, Frank and Don, ages nine and eleven, and went to Gay’s Lion Farm, a provider of exotic animals to movie studios, in hopes of renting Slats, the original MGM lion. In his 2016 memoir So As I Was Saying …, Frank writes that as the lion was unavailable, Herman settled on a cougar, which he took on a leash to the train station in Pasadena. Frank recounts the meeting: “‘That’s a good-looking bunch of backs,’ my father remarked to Coach Little as the boys emerged from the train. ‘Backs, hell,’ the coach replied, ‘that’s the whole team!’” Short-handed and heavy underdogs, the Lions won, 7–0 — the biggest upset in Rose Bowl history.

It was one triumph that Herman could enjoy. Professionally, he was miserable. Despite his having scripted the 1933 hit comedy Dinner at Eight, directed by George Cukor and based on the play by Kaufman and Edna Ferber ’31HON, Herman just couldn’t take Hollywood seriously. He drank, insulted executives, got fired and hired and fired again, drank some more, and was always two steps behind the bill collector. As Davis tells it, by the fall of 1939, Herman, debt-ridden, jobless, alcoholic, and forty-two years old, decided to get a ride with a friend cross-country to New York — home of the theater, the magazines, and all he’d left behind — to salvage himself.

But in New Mexico the car crashed. Herman broke his leg and was hospitalized in Los Angeles. Among his visitors was a twenty-four-year-old director named Orson Welles, cofounder of the Mercury Theatre. Herman and Welles had lunched the year before — the year that Welles’s radio play The War of the Worlds had persuaded many Americans that Martians had invaded New Jersey — and the two boy geniuses, current and former, had hit it off. Welles, who had just signed an extraordinary two-picture deal with RKO giving him full creative freedom, needed material. Now he offered Herman money to write a few radio scripts — uncredited — and Herman, desperate for cash, agreed.

Then they started talking about a movie, and about journalism and politics and power. Herman knew the publishing titan William Randolph Hearst personally and had dined more than once at the Hearst Castle in San Simeon. An idea began taking shape, and in February 1940 the broken-down screenwriter went into seclusion in Victorville, California, and wrote his masterpiece.

That same year, Joe got his second Oscar nomination as producer of The Philadelphia Story, having earned his first in 1931 as a screenwriter for Skippy. Herman, one of the highest-paid writers in Hollywood, had yet to be nominated once.

But in 1941, just when it seemed like Herman was sunk, his ship came heaving into port. Citizen Kane was a critical success. Though he had agreed to work uncredited (Welles’s RKO contract called for Welles to be billed as writer and director), Herman reversed himself and demanded that his name appear. Welles consented, but the question of authorship remains one of Hollywood’s enduring mysteries (as dramatized in David Fincher’s 2020 film Mank). Frank contended that his father was sole author, while others see a clear collaboration. But it was Herman who got top billing, Herman whose name was read first over the radio as winner for best original screenplay of 1941. Herman didn’t attend the ceremony but later claimed he had prepared a speech that said, “I am very happy to accept this award in Mr. Welles’s absence, because the script was written in Mr. Welles’s absence.”

If Herman’s win was a defeat for Joe in the zero-sum game of Mankiewicz achievement, Joe lost ground again the following year, when Herman was nominated for another screenwriting Oscar, this time for The Pride of the Yankees, a biopic about former Columbia baseball star Lou Gehrig (in which Low Library and Alma Mater make a cameo).

But Joe was just warming up. He finally directed his first picture, a period drama called Dragonwyck, in 1946, and just a few years later became the only person ever to win Oscars two years in a row for writing and directing: in 1950 for A Letter to Three Wives and in 1951 for All About Eve, the movie in which his abiding themes of ambition and usurpation were most splendidly realized.

Despite this success, Joe was not immune to the nagging sense that movies lacked the heft of theater or literature. Like Herman, he longed for New York, and in 1951 he and his wife, the Austrian-born actress Rose Stradner, and their sons, Tom Mankiewicz and Chris Mankiewicz ’63CC (both of whom would work in the movie industry), migrated to the Upper East Side. Joe started his own production company, and his remarkable run of films through the 1950s — including No Way Out, featuring newcomer Sidney Poitier; Julius Caesar, in which Joe cast Marlon Brando as Mark Antony; The Barefoot Contessa, for which Joe received an Oscar nomination for best original screenplay; and Suddenly, Last Summer, based on the Tennessee Williams play — sealed his reputation as America’s most literate director and, in the words of Jean-Luc Godard, “the most intelligent man in all contemporary cinema.”

Joseph L. Mankiewicz had reached the top of his profession in every way, and had certainly earned the respect of his peers. As president of the Screen Directors Guild during the height of the Red Scare, Joe, a Republican, refused to institute loyalty oaths for members, despite pressure by guild anti-communists. He was also an outspoken advocate for civil rights. But behind the courtly Park Avenue élan there lurked another aspect of his identity: the serial philanderer who slept with several actresses. His son Chris has described Joe as a distant father and gaslighting husband whose infidelities and denials overwhelmed Rose, who suffered from mental illness exacerbated by alcoholism. In 1958, Rose committed suicide. Joe remarried in 1962. At the time, he was filming Cleopatra, starring Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton, a chaotic, budget-busting production that almost derailed his career. Fortunately, he went out on a high note in 1972 with his last film, Sleuth, which earned Oscar nods for Joe and his two-person cast of Laurence Olivier and Michael Caine.

Joe’s greatest love had always been the theater, and toward the end of his life he wondered what books and plays he might have written, had he taken the more academic Erskine-Pop path. “I wish now that I had done that,” he said. “I would have had something I did that stood for something.” His Oscars, he said, “don’t give what I call a standing.”

But if Joe felt uncertain of his legacy, others affirmed his greatness. In 1986, Columbia feted him with the Alexander Hamilton Medal, the College’s highest honor. The following year he received the Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement at the Venice Film Festival. And in 1988, France bestowed him with one of its highest decorations, the Chevalier de la Légion d’Honneur. Joe died in 1993, having outlived his brother by forty years.

Poor Herman did not live to see Citizen Kane, which Hearst had used his power to suppress, be rediscovered and canonized by critics twenty years after its release. He died in 1953 of kidney failure at age fifty-five.

Ben Mankiewicz never met his grandfather, but he has introduced many of his movies on TCM and often thinks about him. “The tragedy of Herman is not the drinking or the gambling or the getting fired,” says Ben. “The tragedy of Herman is that he didn’t recognize that what he did mattered. If I could say one thing to my grandfather, it would be ‘Hey. Idiot. You’re the idiot. Movies are a real art form, and you should be proud, not torturing yourself.’”

When people know that your grandfather wrote Citizen Kane and your great-uncle wrote and directed All About Eve, there is, says Ben, a certain “burden of expectation” — a presumption that if your name is Mankiewicz you are sure to be the brightest, funniest person at the table. Ben feels that the one Mankiewicz who really lived up to the name was his father, Frank.

“He was fun to hang out with, fun to watch baseball with, and the smartest person in whatever room he was in,” says Ben. “He was also a great listener. My brother [Dateline journalist Josh Mankiewicz] and I adored him. He was ninety when he died in 2014, and I still feel we lost him too young.”

Frank, having watched his father’s struggles in the movie industry, studied law at UC Berkeley and journalism at Columbia, and became a Hollywood lawyer instead of a writer (Steve McQueen was a client). His life changed when he heard President John F. Kennedy’s call to service during his inaugural address in 1961. Frank took a position with the newly established Peace Corps and soon became its Latin American director. He later became press secretary to Senator Robert F. Kennedy, working for him through his 1968 presidential campaign, which ended in gunfire at the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles. It was Frank who, on June 6, 1968, at Good Samaritan Hospital, delivered the news on live TV that Kennedy had died.

In the 1970s, Frank became president of National Public Radio, where he greatly expanded operations and oversaw the creation of Morning Edition. But movies never reached him. It was only by watching Ben on TCM that he discovered the jewels of the family business.

That included work by his brother, Don Mankiewicz ’42CC, who was nominated for an Oscar for his 1958 screen adaptation of I Want to Live!, loosely based on the true story of a woman convicted of murder and executed in California’s gas chamber in 1955. At Columbia, Don wrote for the Jester, was on the debating team, ran for class secretary (he lost), and after graduation became a novelist (his best-known book, Trial, was made into a movie starring Glenn Ford). He was also a scriptwriter and wrote the pilots for the hit television shows Ironside and Marcus Welby, MD. Some of his best work was done for the live black-and-white TV-playhouse programs of the 1950s and early ’60s, with their voice-over narration, Chesterfields, and orchestral stabs. He adapted Robert Penn Warren’s political novel All the King’s Men into a two-parter for Kraft Television Theatre, directed by Sidney Lumet, and for Playhouse 90 he adapted The Last Tycoon by F. Scott Fitzgerald, directed by John Frankenheimer.

Don died in 2015, and the portrait of Franz, which had been in his house, was eventually given to Ben. Franz had died in 1941, the year Citizen Kane was released. He never saw his sons win awards or be honored by nations, never saw the ways in which all the Columbia Mankiewiczes would use their love of storytelling to instruct, delight, and inspire.

Five years ago, Ben began pushing for a podcast at TCM. It was named The Plot Thickens, and Ben’s friendship with the late director and raconteur Peter Bogdanovich became the basis for its first season. In the latest season, titled “Lucy,” Ben narrates the life story of Lucille Ball. “Normally at TCM you talk for two minutes before a movie,” Ben says. “This is ten forty-five-minute episodes — about seven hours. You can tell a pretty great story in seven hours.”

Of course, Ben can tell a great story in two minutes, just as his grandfather and great-uncle could tell a magnificent one in two hours. But none of them, for all their narrative gifts, could have produced a plot as thick as the one that drives the tale of the Columbia Mankiewiczes — four generations of talented men separated by time and temperament, the threads of their lives woven together through the medium of that uniquely American art form, the classic Hollywood movie. And as Ben, standing before the camera, introduces the Marx Brothers’ Duck Soup (produced and cowritten by Herman) or the musical Guys and Dolls (directed and scripted by Joe) — or Citizen Kane or All About Eve — he draws those threads a little closer.

This article appears in the Fall 2022 print edition of Columbia Magazine with the title "Being the Mankiewiczes."