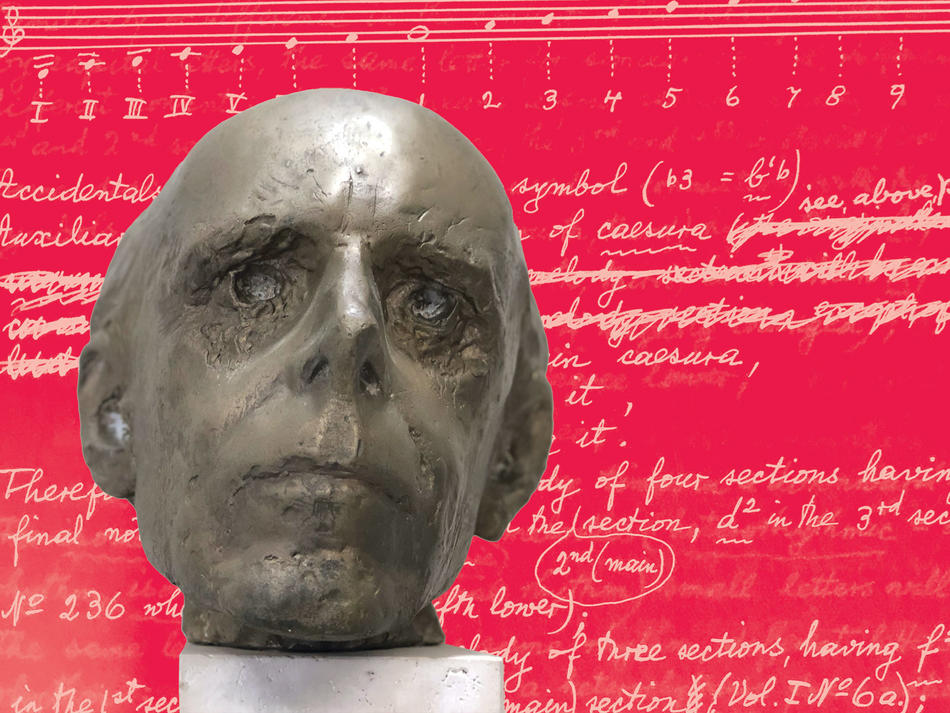

WHAT IS IT? Bronze sculpture of composer Béla Bartók, by Tibor Borbás

WHERE'S IT FROM? Hungary

WHERE CAN I FIND IT? Gabe M. Wiener Music and Arts Library, seventh floor of Dodge Hall

"His was a strong soul in a body frail but intense, with penetrating bright eyes, lively gestures, precise and ready words, always alert and courageous, as if the whole man were the blade of intelligence drawn from its sheath,” wrote Columbia musicologist Paul Henry Lang of his Hungarian compatriot Béla Bartók '40HON. Lang, who taught at Columbia from 1933 to 1970 and wrote the seminal Music in Western Civilization, considered Bartók the greatest composer of the twentieth century.

Born in 1881 in the Kingdom of Hungary, in a town now in Romania, Bartók spent his twenties traveling the countryside of Central Europe, recording and notating the unwritten music of peasants and the Roma. He began fusing those melodies and rhythms with the Western romanticism of Brahms and Richard Strauss, creating a hybrid by turns heroic, melancholic, and, to many ears, macabre. (Stanley Kubrick would use Bartók’s Music for Strings, Percussion, and Celesta in the hallway scene in The Shining.)

In 1940, Bartók, appalled by rising fascism, left Hungary, where he was a national hero, and settled, penurious and anonymous, in New York. At Lang’s behest, Columbia created a modest research position in the anthropology department and hired Bartók, a pioneer of ethnomusicology, to transcribe and analyze a collection of Balkan folk songs. When funds for the project ran out in 1942, Bartók’s colleagues raised money to extend the appointment. The following year he composed Concerto for Orchestra, perhaps his best-known work.

While at Columbia, Bartók also wrote a commentary on some 2,556 transcribed Romanian folk songs. In it he mourns the loss of this “unspoiled” music to the forces of “urban civilization.” Upon his death in 1945, Bartók left this handwritten manuscript to Columbia, where it remains in the archives. In 1984, the Hungarian People's Republic presented a bust of Bartók to Columbia. The sculpted likeness, which sits in Dodge Hall, still looks on with probing eyes, alert and courageous.

This article appears in the Summer 2019 print edition of Columbia Magazine with the title "Hungarian Rhapsody."