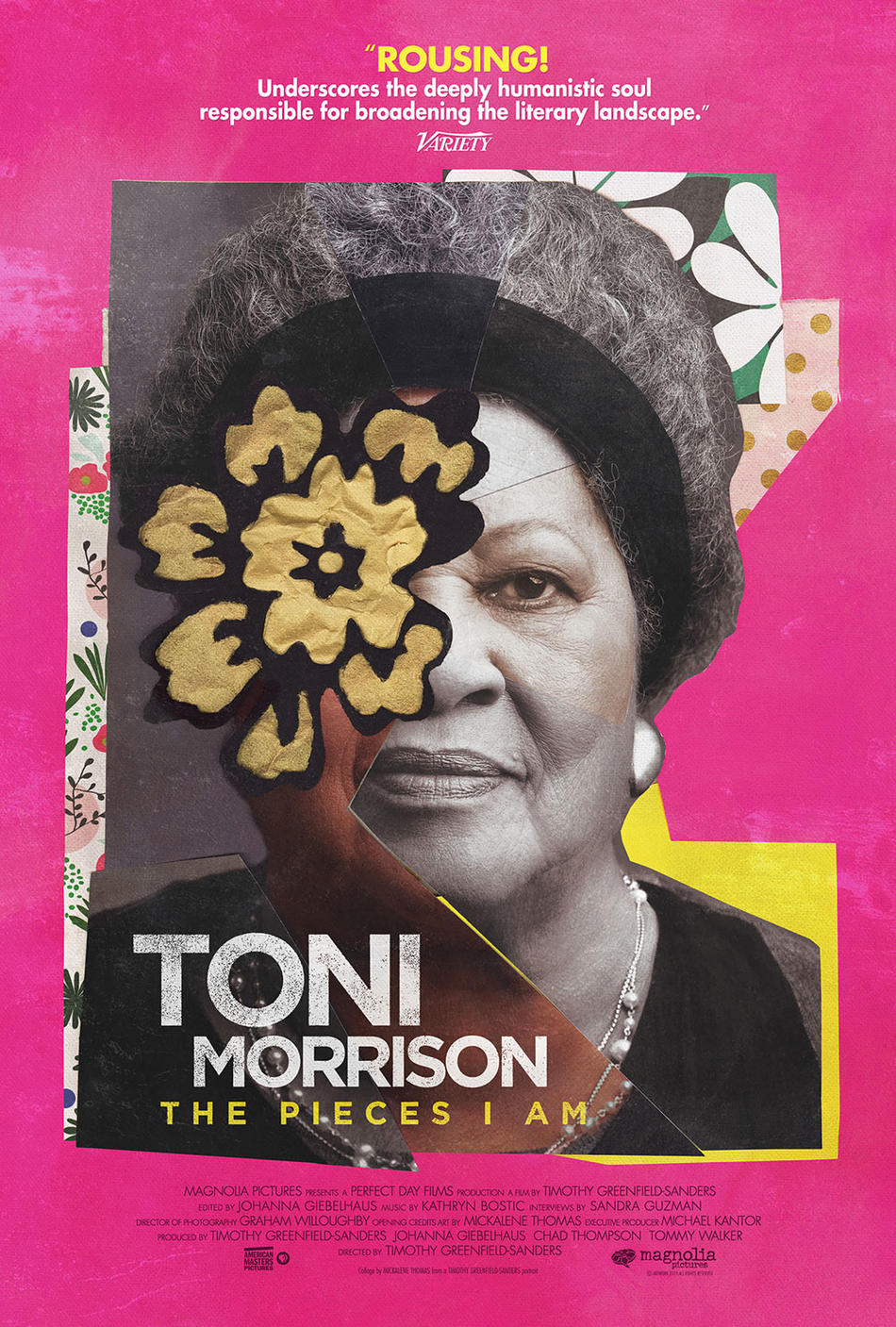

In the opening of the dazzling new movie Toni Morrison: The Pieces I Am, a photo collage reveals a series of defining moments in the writer’s life. There’s Morrison the young book editor in New York sporting an afro and Morrison the literary superstar smiling serenely for a press photo. In the last image we see Morrison the cultural icon, an elegant elderly woman looking deep into the camera with soulful eyes. The portrait is intimate and candid, suggesting a trust between subject and photographer forged over many years. It was taken by Timothy Greenfield-Sanders ’74CC, the documentary’s director.

The unlikely friendship between Greenfield-Sanders, a photographer famous for his unflinchingly direct portraits of celebrities, and Toni Morrison, a notably press-shy writer who passed away on August 5 at the age of eighty-eight, is the heart and the engine of this two-hour film, which was released in theaters in June and is available to stream on Hulu starting September 17.

“Toni Morrison was really one of the greatest artists of our time; there was no one like her,” says Greenfield-Sanders, who first met Morrison in 1981 when he took her picture for the SoHo Weekly News after the release of her fourth book, Tar Baby. “Toni and I hit it off,” he says. “I remember this confident presence in the studio, smoking a pipe.” After that, Morrison frequently chose Greenfield-Sanders to photograph her for press pictures and book jackets. As Morrison said in an interview this summer, “I trusted him, and I still trust him.”

So it makes sense that the author allowed Greenfield-Sanders to expose the “pieces” of her life on film. In the movie we are reminded of Morrison’s momentous contributions to American literature — not only as the author of richly textured, harrowing novels like The Bluest Eye and Beloved but also as an editor at Random House, where she helped introduce Black writers like Gayl Jones and Toni Cade Bambara to the masses.

In the film Greenfield-Sanders uses his signature style of portraiture — in which the subject, positioned against a plain backdrop, stares into the camera — to capture Morrison as she tells her own story. She reflects on her upbringing in working-class Ohio, on the criticism she received for writing books that were “too Black” and “too female,” and on the sheer joy she felt in winning the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1993. At times she is surprisingly frank. Reminiscing about her college years at Howard University, she laughs and declares, “I was loose!” “It’s a Toni that very few people got to see,” says Greenfield-Sanders.

The director illustrates Morrison’s narrative by splicing in works by African-American visual artists, such as Kerry James Marshall and Kara Walker. He also features interviews with some of Morrison’s collaborators and admirers. Oprah Winfrey and Angela Davis, as well as Farah Jasmine Griffin, the chair of Columbia’s new African American and African Diaspora Studies department, and Hilton Als, the Pulitzer Prize–winning theater critic and Columbia professor, give perspectives on Morrison’s influence on their lives and our culture.

Greenfield-Sanders studied art history at Columbia, then attended the American Film Institute in Los Angeles, but he initially eschewed filmmaking in favor of photography. He preferred that medium, he says, because it allowed him to work alone, without a crew. At AFI he got a job photographing the school’s visiting dignitaries — Hollywood legends like Bette Davis and Alfred Hitchcock ’72HON — and became comfortable mingling with the stars. In fact, it was Davis who gave Greenfield-Sanders some of his most important lessons in photography. As he tells it, he bent down to take her photo from a low angle, and she snapped, “What the fuck are you doing shooting from below?” Davis offered to teach him about portraiture if he’d drive her around Hollywood, and he accepted.

Since then, Greenfield-Sanders has photographed countless famous figures, from Andy Warhol to Beyoncé, Donald Trump to Elizabeth Holmes. He works out of his home, a former church rectory in the East Village, and shoots in large format with a vintage Deardorff 8 × 10 camera. The tedious process requires looking at the image upside down and making sure his subject stays very still. “I like the challenge,” he says, adding that he only takes a few photos per shoot. “Some photographers just keep shooting and shooting, and eventually they get something. I don’t think that’s really the art of portraiture.”

Greenfield-Sanders got into filmmaking in the 1990s when he made Lou Reed: Rock and Roll Heart, a documentary for PBS about the musician and Velvet Underground frontman. The movie went on to win the 1998 Grammy Award for Best Music Film. In 2008 Greenfield-Sanders released The Black List, a series of “living portraits” of notable African-Americans speaking about their experiences with race and identity. Filming Morrison for the project, Greenfield-Sanders decided he wanted to make her story into something bigger. “I immediately knew she deserved her own feature documentary,” he says.

Greenfield-Sanders says he thinks the film has particular resonance right now. “You can’t look at Toni’s struggle and ideas and not feel like they have real currency in this political climate,” he explains. “We live our lives, get older, and often miss the right moment to capture an extraordinary life, with the subject fully engaged. I just felt it was time to film Toni’s story.”