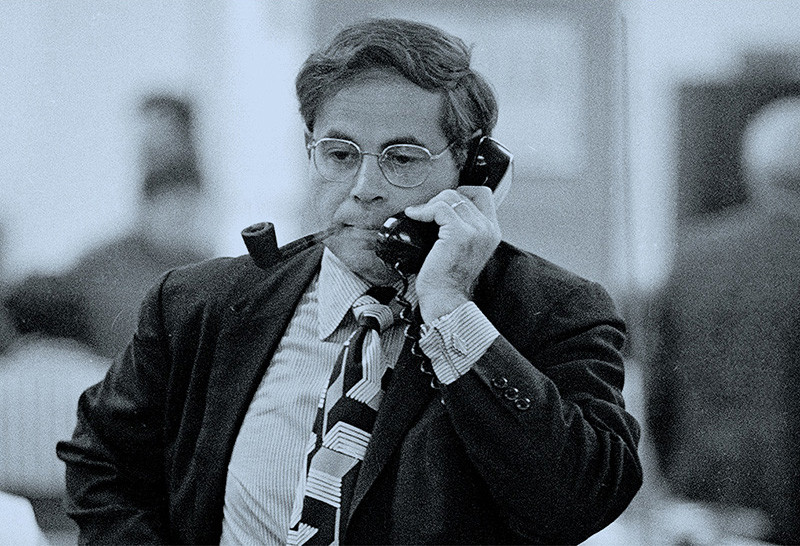

Max Frankel ’52CC, ’53GSAS remembers the first time he laid eyes on the Pentagon Papers.

It was March 1971, and Frankel was Washington bureau chief of the New York Times. A reporter, Neil Sheehan, had brought him some pages of a classified government report that an anonymous source had offered him. The material was about the war in Vietnam, and the pages, Frankel saw, were stamped top secret — sensitive.

“I could recognize that the documents were legitimate, and much like the ones I’d seen while covering diplomacy and military affairs,” says Frankel, a Pulitzer Prize–winning journalist who joined the Times out of college, rose to the position of executive editor, and retired from the paper in 2000.

Now ninety-one, Frankel recalls his excitement as he read over the papers. “When you see messages between General Westmoreland and [Secretary of Defense] McNamara, and it’s top secret — then you know it’s going to be very dramatic reading for anyone interested in how government works,” he says.

The pages covered the 1964 Gulf of Tonkin incident and raised questions about the official claim that North Vietnamese boats fired at American ships, a supposedly unprovoked attack that gave President Lyndon B. Johnson justification to seek broad war powers.

“I saw this information as being of interest to the public: a history done by the government itself, answering the crucial question of how we got sucked into this war. I said, ‘If that’s the quality we’re going to get out of this document, well, that’s gonna be a hell of a story.’”

Seated at his desk that day, Frankel could not have imagined that this “scoop of a lifetime,” as it would be hailed, would absorb the Times in a high-stakes legal and moral drama packed with intrigue, journalistic heroism, presidential paranoia, and prosecutorial peril. On Tuesday, June 15, 1971, two days after the Times began releasing excerpts of the Pentagon Papers, the Justice Department under President Richard Nixon filed an injunction to stop publication. Never before had the federal government tried to impose prior restraint — preemptive restrictions on what could be said or written — against a newspaper. To many, it was an unthinkable challenge to the First Amendment’s promise that “Congress shall make no law … abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press.”

With the Times asserting its right to inform the public about the evolution of an increasingly bloody war — and with Nixon claiming threats to national security — the case shot to the Supreme Court and became an instant touchstone of First Amendment jurisprudence.

“I think the Pentagon Papers case is one of the two or three most important and interesting First Amendment cases of the modern era,” says University President Lee C. Bollinger, a preeminent First Amendment scholar. “Every democratic society has to figure out how to deal with this problem: governments need secrecy in order to operate, but they also tend to be overly secretive. How do you strike that balance between secrecy and the public’s right to know?”

In its varied rulings and opinions, the case offered a kaleidoscopic answer, and the issues it spotlighted still burn bright. Who should decide what gets published? What is the nature of classification? Are people who leak information to the press traitors or patriots? Should they receive protections or punishment? Is press censorship ever appropriate?

“The great thing about the First Amendment is that it’s always a reflection of how we understand the most basic elements of our political system and our social system,” Bollinger says. “Our attitudes about the role of citizens, the role of the press, the role of public servants, and the role of the courts, and the Supreme Court in particular — the Pentagon Papers is one of those grand moments when all of these vital questions come into sharp relief.”

That a prominent case at the intersection of journalism, foreign affairs, and constitutional law should feature a cast of Columbians is hardly surprising, but in the beginning, none of those key players could have predicted just where the story was headed.

Certainly this was true of Morton Halperin ’58CC, who in June of 1967 was a twenty-nine-year-old aide to defense secretary Robert McNamara. A political science major at Columbia, Halperin was a brilliant young academic who taught at Harvard with Henry Kissinger and entered government in 1966 to work in the Johnson Pentagon. Now, a year later, with the war intensifying, McNamara asked Halperin to manage a critical project: an “encyclopedic” study of US involvement in Vietnam since 1945. For McNamara, the Vietnam War, which he had helped design, seemed unwinnable, and he wanted to trace the anatomy of the quagmire for future researchers.

He also wanted the project kept secret.

“We were trying to keep it secret not from the Russians or the Chinese but from Lyndon Johnson,” says Halperin, eighty-two, who has served as a foreign-policy analyst under three presidents. “That’s because LBJ believed there were civilians in the Pentagon who were trying to undercut his policy and get us out of Vietnam, which was true. We thought, ‘If he finds out we’re doing this, he’ll just shut it down.’ So we told everyone we talked to that they couldn’t tell anyone about the study, that it was under McNamara’s direction and being very closely held.”

Halperin brought in Defense Department official Leslie Gelb to run the project full-time and continued to supervise and help recruit authors. Due to the secret status of the report, these authors needed security clearance, so Halperin turned to the RAND Corporation, a defense-policy think tank with government contracts. Among his RAND hires was Daniel Ellsberg, a Harvard-trained defense analyst who had once been hawkish on the war.

The project crept along for eighteen months. Finally, in January 1969, five days before Nixon took office, the Report of the Office of the Secretary of Defense Vietnam Task Force — soon to be known as the Pentagon Papers — was complete. Written by thirty-six policy experts, historians, and military officers, the report consisted of seven thousand pages of narrative, analysis, and supporting documents, divided into forty-seven volumes. It revealed the inner workings of Vietnam policy over four administrations and contained explosive evidence that the government had deceived the public about the war at every juncture.

Halperin and Gelb made fifteen copies of the study, and Halperin saw to it that every page was marked “top secret.”

They deposited one copy each in the Johnson and Kennedy libraries, gave several to former officials and one to Kissinger (who was Nixon’s national security adviser), put five in a safe at the Pentagon, and kept a copy for themselves, which they stored at RAND. The president of RAND, Henry Rowen, insisted on sharing it with Ellsberg, who had top clearance. Halperin yielded, but he worried what might happen if Ellsberg saw the whole thing. “Dan was a great believer that providing information to people could change their hearts,” says Halperin. “I knew he would leak the papers.”

Sure enough, Ellsberg, with help from colleague Anthony Russo, made his own copy of the classified report, offered it to sympathetic senators, and, finding no takers, picked up a phone in February 1971 and called Neil Sheehan, a Vietnam War correspondent for the New York Times.

The papers were spirited from Cambridge (where Ellsberg lived) to Washington, DC, to New York, where the Times editors set up a covert operation out of the Midtown Hilton to vet and organize the red-hot material. A team of reporters and editors combed through the papers to make sure that any military secrets that would endanger troops or reveal the identities of CIA agents would not be published. Then they prepared summary articles. It took three months.

Anxiety was running high at the Times. The editors had to persuade the publisher, Arthur Ochs “Punch” Sulzberger Sr. ’51CC, ’92HON, that the newspaper had a journalistic obligation to publish — and would lose its integrity if it didn’t. The company’s outside counsel, Louis Loeb 1922LAW, ’70HON, senior partner at Lord Day & Lord, had advised the Times that publishing secrets in wartime not only could send Sulzberger to jail but would be an act of betrayal. “Punch Sulzberger was a former Marine,” says Frankel, “and considered himself a very loyal and patriotic fellow with an obligation to his government. So he took that advice very seriously.”

To reduce their legal risk, Sulzberger suggested that they publish only the reporters’ summaries. Frankel, who adhered to the credo espoused by legendary Times correspondent James Reston ’63HON — “publish and be damned” — argued, along with others, that the supporting documents were essential.

Sulzberger had become publisher eight years before, succeeding his brother-in-law, whose sudden death had thrust the humble, unpretentious Punch into a position of vast influence. As a Times article later noted, “Many Times executives and close relatives felt Arthur was too young and not up to the challenge.” But his skeptics had watched him grow into a principled publisher who expanded the paper and left the editing to his editors. Now, facing potential criminal prosecution and with the fate of his family’s paper in his hands, he had to make the biggest decision of his career.

In June 1971, in the hours before he was to take a trip to London, Sulzberger summoned the editors to the boardroom. “Punch was sitting at one end of the table,” Frankel recalls. “He said, ‘I’ve reached a decision: you can print the documents but not the narrative.’ It was his jocular way of saying: publish and be damned.”

On Sunday, June 13, the front page of the Times featured an article on the wedding of Nixon’s daughter. Beside it was an item with the purposely understated headline “Vietnam Archive: Pentagon Study Traces 3 Decades of Growing U.S. Involvement.”

The next day, after the Times had published its second installment of the Pentagon Papers series, Attorney General John Mitchell telegrammed the Times a demand to halt further publication and turn over the documents, claiming the leaks would cause “irreparable injury to the defense interests of the United States.” He also invoked the Espionage Act of 1917, a law passed during World War I to punish spies.

Sulzberger, in London, refused to censor his newspaper. (Later he would say he was “scared to death.”) On June 15 the federal government sued to stop the Times from publishing.

“The next thing we knew,” says Frankel, “we were headed to court.”

Floyd Abrams, a renowned attorney who has argued thirteen cases before the Supreme Court, and who is currently a lecturer in law at Columbia, was a thirty-four-year-old lawyer in 1971. He recalls being at a lunch with First Amendment scholar Alexander Bickel, his professor at Yale, the day after the Times broke the story. “People were asking us what we thought of the publication of the papers,” says Abrams. “And Bickel and I, with the enormous freedom of lawyers commenting on cases they are not involved in, said, ‘Oh, the Times is safe. We don’t have prior restraints on what news can be published in America.’”

But after the government filed suit, attorney Loeb, who had represented the paper for two decades, declined to defend the paper’s actions in court. “So the Times called Bickel, and then they called me to work with him on the case,” says Abrams. “My life changed from that moment.”

For many people, an official stamp of secrecy carries the weight of indisputable authority. Most lawyers and judges treated it that way in 1971, but Frankel was one of the few Americans who really grasped how Washington trafficked in secrets. When lawyers from Abrams’s firm who were working on the case questioned what the Times had done, Frankel was furious. “They were under the impression that secrets were secrets, and that any judge would see it that way.”

In response, Frankel produced a remarkable memo that would become another celebrated document of the case: a thirty-seven-point missive meant to educate the legal team. “The government’s unprecedented challenge to the Times … cannot be understood, or decided, without an appreciation of the manner in which a small and specialized corps of reporters and a few hundred American officials regularly make use of so-called classified, secret, and top secret information and documentation,” he wrote. “To hide mistakes of judgment, to protect reputations of individuals, to cover up the loss and waste of funds, almost everything in government is kept secret for a time and, in the foreign policy field, classified as ‘secret’ and ‘sensitive’ beyond any rule or law or reason.” The memo was so eye-opening that Bickel and Abrams drafted it as an affidavit, signed by Frankel, to attach to their court filings.

On Tuesday, June 15, counsel for the Times and the government met in the Foley Square courtroom of Judge Murray Gurfein ’26CC, whom Nixon had just appointed to the US District Court for the Southern District of New York. It was Gurfein’s very first case on the bench. Gurfein, who had been a military intelligence officer during World War II, issued a four-day restraining order on the Times — painful to the paper and to press freedoms — and told the government’s lawyers to examine the papers and show him specific items that, if published, would harm national security. “They could not point to a single document that met even the loosest criteria of importance to national security,” Frankel says.

Gurfein denied the government’s bid for a preliminary injunction — in effect, a prior restraint — and his opinion became a First Amendment classic. “The security of the Nation is not at the ramparts alone,” he wrote. “Security also lies in the value of our free institutions. A cantankerous press, an obstinate press, an ubiquitous press, must be suffered by those in authority in order to preserve the even greater values of freedom of expression and the right of the people to know.”

The US appealed this decision, and when a panel of judges kicked the case back to Gurfein for another hearing, the Times appealed to the Supreme Court. On June 26, opening arguments began in New York Times Co. v. United States.

Bollinger, who had just graduated from Columbia Law School, was glued to the coverage. “This case was front and center for me,” he says. “My father ran a small-town newspaper, I grew up in a newspaper environment, I worked at a newspaper. So the Pentagon Papers had a deep personal significance.”

On June 30, the court, in a 6–3 decision, ruled that the government had failed to meet the “heavy burden” of showing justification for prior restraint. It allowed the Times (as well as the Washington Post, which had joined the case) to continue to publish the Pentagon Papers.

In the end, says Frankel, the defense got certain justices “to accept the formula that in effect became the law: that the government would have the right to restrain us if they could show that something we would publish would ‘surely result in direct, immediate, and irreparable damage’ to the country. Those words from Justice Potter Stewart’s opinion were the heart of the case.”

But even concurring judges felt that the material would be harmful and noted that while the government couldn’t stop publication, it might bring criminal charges against the Times after the fact.

“We were disappointed that we didn’t get a clear judgment from the whole court,” Frankel says. “But looking back it was a big victory: the court came up with a formula — a burden of proving direct, immediate, and irreparable damage — that has withstood challenge. No other attempt at prior restraint has gotten very far since then.”

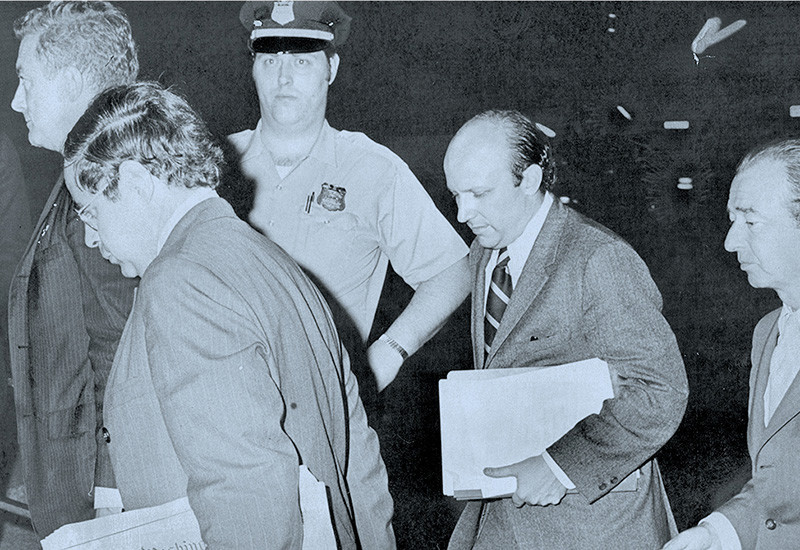

The Nixon administration chose not to prosecute the Times, but it did charge Ellsberg (and Anthony Russo) under the Espionage Act. Facing up to 115 years in prison, Ellsberg was tried in federal court in Los Angeles. But the trial was so riddled with revelations of government misconduct — including the illegal 1969 and 1970 wiretapping of Mort Halperin’s phone, which picked up Ellsberg’s voice — that the judge dismissed the case.

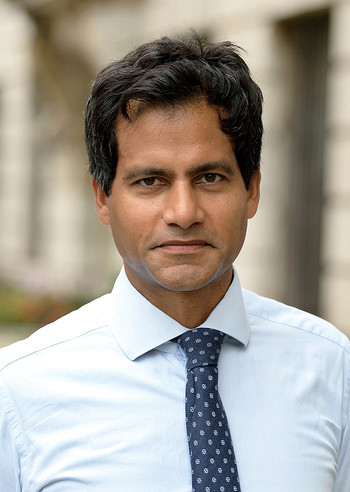

“The Pentagon Papers case is a pillar of the American free-speech tradition and of the freedom of the press in particular, and its significance has only grown over time,” says Jameel Jaffer, executive director of Columbia’s Knight First Amendment Institute, founded in 2016 to defend free speech and the press in the digital age. Digital technology, Jaffer says, has transformed the landscape — Ellsberg had to photocopy seven thousand pages, while today’s leakers can download hundreds of thousands of documents to a flash drive — but the issues of national security, press freedom, and the treatment of whistleblowers are as urgent as ever.

In a new book of essays titled National Security, Leaks & Freedom of the Press: The Pentagon Papers Fifty Years On, Bollinger and University of Chicago law professor Geoffrey R. Stone assemble a roster of top legal scholars, journalists, and national-security experts to assess the case through a contemporary lens. Avril Haines, former deputy director of Columbia World Projects and now US director of national intelligence, discusses the “fight for balance” between the forces of secrecy and transparency; Jaffer examines the need to protect national-security whistleblowers, who have exposed secrets such as the Abu Ghraib abuses and bystander casualties of drone strikes; and others address overclassification, the Espionage Act, the post-9/11 security state, and disparities in legal protections for the press and leakers.

“While we celebrate the strong protections the courts have extended to the press, the position of journalists’ sources has deteriorated,” says Jaffer. “People who are tempted to disclose government secrets to expose abuses must now think about the possibility of a long prison term, even if their disclosures are entirely defensible: technology makes it easier to track them down, and the government has used the Espionage Act much more aggressively.”

Jaffer notes that before 9/11, with the exception of Ellsberg, Russo, and Samuel Morison, who gave classified satellite photographs to Jane’s Defence Weekly in the 1980s and was later pardoned by President Clinton, no one was prosecuted under the Espionage Act for giving information to the press. “But since 9/11, there have been many cases,” he says. “Now it’s not uncommon for journalists’ sources to be prosecuted under this 1917 law that was supposed to be about spies. Morally it’s difficult to explain why journalists who publish classified secrets are given prizes [the Times won the 1972 Pulitzer Prize for public service for its Pentagon Papers coverage], while the people who disclose those secrets are threatened with prison.”

Columbia law professor David Pozen, an expert on leaks, shares this concern. “I view the laws against leaking in the US as quite draconian,” he says. “Any ‘give’ in the system favoring the leaker comes not from the laws but from non-enforcement of the laws.”

“The Espionage Act needs to be amended; it’s an anomaly in our legal system,” says Bollinger. “I’m hopeful that under the Biden administration, and at this moment of the fiftieth anniversary of the Pentagon Papers, we can get some congressional action in changing the law.”

The Knight Institute, which uses litigation, research, and public education to protect online discourse, has called on the administration to drop the case against WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange, which Jaffer regards as a “major threat to press freedom.” In 2019, Assange was indicted on seventeen counts under the Espionage Act for the 2010 publication of thousands of documents supplied by Army soldier Chelsea Manning, some of which revealed US war atrocities and lies about the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Jaffer also calls the Espionage Act charges against Edward Snowden “a travesty” and says that the former CIA contractor, who copied 1.5 million NSA files, including data on a secret warrantless surveillance program, and gave them to journalists at the Guardian, performed “an immense public service,” noting that multiple courts later found the program to be unlawful.

Differing opinions on Snowden appear in Bollinger and Stone’s book, but few would argue with Bollinger’s assertion that computers and the Internet have “undermined the conventional model of the traditional media” and widened the field of potential leakers. “At the time of the Pentagon Papers, you had the New York Times and the Washington Post, absolutely responsible institutions that you could count on to go through the documents, weigh the national-security interest against the public’s right to know, and reach a decision,” he says. “Now you have entities like WikiLeaks, whose basic philosophy is that everything should be public and that governments have no right to operate in secrecy. That increases the risk of damaging disclosures enormously.”

Abrams concurs. “That the Times published far less than seven thousand pages of that heavily classified study and made an effort to avoid publication of certain materials was commendable on every level,” he says.

For Abrams, one enduring lesson of the Pentagon Papers case is that we should reserve some healthy skepticism when the government claims that publication will do grave harm. “In any single case, of course, they may be accurate,” he says. “But fifty years ago, the claim by a significant number of people in power, and not just in the Nixon administration, was that allowing the publication of the Pentagon Papers would do enormous damage to the nation. And that didn’t happen.”

In his course Ideas of the First Amendment, which he co-taught this spring at Columbia with civil-liberties scholar Vincent Blasi, the syllabus covers James Madison’s Virginia Report of 1799–1800, challenging the Alien and Sedition Acts; John Stuart Mill’s On Liberty; and First Amendment opinions in American legal history, including selections from a case that Abrams knows well — and one that he’d defend to the end.

“Through the years, the Pentagon Papers decision has served as an ongoing protector of liberty of the press,” he says. “That view of mine hasn’t changed at all.”