Just before midnight on June 24, 1971, Mike Gravel ’56GS, Democratic senator from Alaska, drove to the Mayflower Hotel in Washington, DC, five blocks from the White House. The streets were quiet, and as Gravel got closer to the hotel he saw a Volkswagen parked in front. In the driver’s seat was Ben Bagdikian, the national editor of the Washington Post. Bagdikian had a package for Gravel: a copy of the top-secret Pentagon Papers, which Daniel Ellsberg, a RAND Corporation defense analyst, had illicitly Xeroxed and handed off to the New York Times and the Post.

The seven-thousand-page document tracing the development of the Vietnam War — much of which contradicted the public statements of five administrations — was, in June of 1971, at the center of a momentous court case: the Times had begun printing excerpts of the classified material in its June 13 Sunday edition, and by Tuesday the Nixon Justice Department sued to stop the newspaper from publishing more. But even before Ellsberg gave a copy to the Times that March, never knowing when or if they would publish it, he had been trying, without success, to find a US senator who possessed both the conviction and the courage to expose the government’s lies.

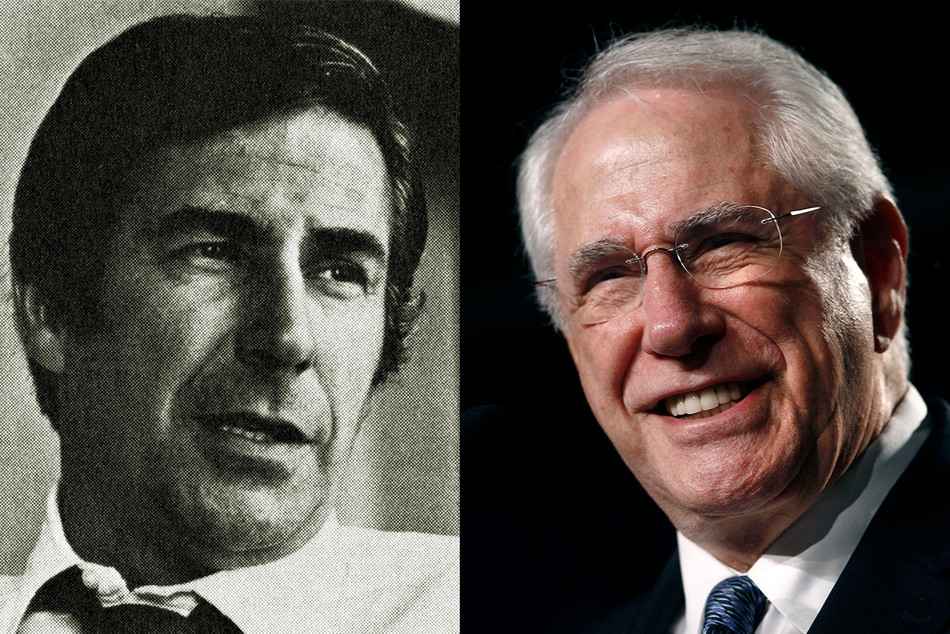

Then, shortly before the Times published, Ellsberg learned that a little-known freshman senator from Alaska named Mike Gravel had begun a filibuster (a tactic that allows a senator to delay a vote on a bill by holding the floor) to stop passage of the extension of the military draft law. He thought: Maybe this is the guy.

No sooner had Ellsberg found his man than the Times published the first installment of its Pentagon Papers series. The Nixon White House cried treason, the courts halted publication, and the FBI identified Ellsberg as the leaker. On Tuesday, June 15, Ellsberg, lying low in Cambridge, slipped out to a pay phone and called Gravel’s office. As he would later recount, he asked Gravel’s aide if his boss planned to continue his filibuster. When the aide said yes, Ellsberg replied, “I’ve got some material that could keep him reading until the end of the year.” He then furnished the Washington-based Bagdikian with documents for both the Post and Senator Gravel.

In truth, Ellsberg could not have found a more suitable conduit than Gravel. No one on Capitol Hill was more passionate about ending the war, and few had Gravel’s flair for showmanship and derring-do. Back in 1950, at the start of the Korean War, Gravel, in a flush of patriotism, and with romantic visions of being a spy, had enlisted in the army and worked in counterintelligence. But even his youthful cloak-and-dagger fantasies were no match for the improbable role that he was now, in June 1971, performing at midnight under the Mayflower marquee: that of a forty-one-year-old senator hoisting boxes of purloined government documents into the trunk of his car.

The idea was for Gravel to read the Pentagon Papers into the Senate record during his filibuster. Legally, he would be insulated by the Speech or Debate clause, a section of the Constitution that imparts immunity to congresspersons for any speech that occurs while that representative is performing official legislative business. This would allow Gravel to circumvent the courts and bring the information into the public sphere.

And so Gravel, his car loaded with the most sought-after documents in the land, drove home through the hushed Washington streets. “When I got home I told my wife I had the papers,” says Gravel, now ninety-one and living in Seaside, California. “She said, ‘We’re going to put them under the bed and sleep on them,’ and that’s what we did.”

Gravel had always been something of a risk taker. Born in Springfield, Massachusetts, he had moved five thousand miles away to Alaska in the late 1950s on the calculation that he could rise faster in politics in a sparsely populated state. He became the speaker of the Alaska House of Representatives in 1965, and then, in 1968, he was elected US senator. During his campaign he did not condemn the war — “It was not in my political interest to fight that battle at that point in time,” he says — but once he was in the Senate he resolved to see the conflict up close. In 1969 he traveled to Vietnam and flew by helicopter into fire zones. “They had two other choppers flying with my chopper — they didn’t particularly want to lose a senator. But I was intent on getting firsthand knowledge of the war, and I did, and I articulated my opposition thenceforward, day in and day out.”

The morning after his Mayflower rendezvous, Gravel awoke with the realization that he would have to actually read the trove of secret documents under his bed. “I couldn’t just throw them out there,” he says. But his dyslexia prevented him from being able to read quickly, and he invited his staff to his house. “I explained to them that I had the papers and needed help to read them, and that they were free to leave if they felt uncomfortable.” Everyone stayed. The staffers slept in Gravel’s living room and went through the papers, and whenever they came across a name they informed Gravel, and he decided whether or not to excise it. “That was a busy, busy weekend,” he says.

On Tuesday, June 29, with the Supreme Court deliberating New York Times v. United States — and with the First Amendment itself hanging in the balance — Gravel stuffed the papers into a couple of large flight bags that he’d bought for the occasion. He was sleepless, running on adrenaline, fear, and moral purpose. The previous month he had visited wounded soldiers at Walter Reed military hospital — a searing experience — and now, wanting to safeguard the papers, he phoned Vietnam Veterans Against the War, a nonprofit started in 1967, and asked them to send some disabled members to his office to help with office security.

Later that day he entered the Capitol carrying the paper-stuffed flight bags. The sight aroused curiosity — senators were not often seen lugging heavy things — but Gravel wanted to shield his staff from liability. As he and his staffers walked down the hall to his office, Gravel spotted his requested security detail. “There were six or seven veterans in wheelchairs doing wheelies around the corner,” he recalls.

That evening in the Senate chamber, Gravel’s plans met resistance. The quorum of fifty-one senators required to conduct Senate business failed to materialize, and when Gravel requested unanimous consent to bypass the quorum rule, the only other senator present, Michigan Republican Robert P. Griffin, objected. That ended the session, and Gravel had to improvise. As chair of the subcommittee on Buildings and Grounds, he called a nighttime hearing in a room across the street in the New Senate Office Building — an official piece of Senate business that could serve as the medium for his task.

The hearing room buzzed with reporters who had been told of Gravel’s plans. Veterans were in attendance, as was John C. Dow ’37GSAS, a Democratic congressman from New York who had been recruited in the hallway to be the witness.

Gravel, dressed in a dark jacket and tie and a white shirt, sat on the rostrum at a dark wooden table. He faced his audience resolutely, masking his inner turbulence. “I was frightened,” he recalls. “There was no precedent for what I was doing. The attorneys helping me out had no idea of the consequences, whether censure, expulsion from the Senate, or jail. We were totally in the dark.”

There was a clutch of microphones on the table before him, and Gravel spoke into them. “The people must know the full story of what has occurred in the past twenty years in their government,” he said. “The story is a terrible one. It is replete with duplicity, connivance, against the public and public officials. I know of nothing in our history to equal it for extent of failure and extent of loss in all aspects of the terms.”

As he spoke, visions of maimed bodies flashed through his sleep-deprived mind.

“People, human beings, are being killed as I speak to you tonight. Killed as a direct result of policy decisions that we as a body have made. Arms, arms are being severed, metal is crashing through human bodies because of a public policy this government” — Gravel, overcome, began to sob. He wiped his face with a handkerchief and composed himself. “One may respond that we made such a sacrifice to preserve freedom and liberty in Southeast Asia. One may respond that we sacrifice ourselves on the continent of Asia so that we will not have to fight a similar war on the shores of America. One can make these arguments only if he has failed to read the Pentagon Papers. That is the terrible truth of it all.”

Gravel began reading the text of papers, and in the wee morning hours of June 30, utterly exhausted, he submitted the remaining pages into the record. Hours later, the Supreme Court delivered its decision in the Pentagon Papers case: in a 6-3 ruling, it affirmed the newspapers’ right to publish the top-secret report.

Many of Gravel’s colleagues were angered by his Senate ploy. Barry Goldwater called him a traitor to his face. There was talk of sanctions. “The Republicans in the Senate, with minority leader Gerald Ford, came over to visit Mike Mansfield, the majority leader,” says Gravel. “They said, ‘We want to talk to you about Gravel,’ and Mansfield, sucking quietly on his pipe, said, ‘Well, I don’t know he’s done anything wrong.’ That cut them off at the knees. Mansfield gave me total protection.

“A day later I went in to see Mansfield and apologize for all I’d done to discombobulate the Senate. As I walked in I was almost in tears. He said, ‘Mike, if I had your courage I would have done the same thing.’ I started to tear up and excused myself. That was a pretty teary three or four days.”

The Supreme Court struck down the government’s attempt to stop a newspaper from publishing material that, in the Court’s view, would not cause “direct, immediate, and irreparable damage” to the country. But it also left open the possibility of criminal prosecutions after publication, and Gravel noticed that newspapers that had excerpted the Pentagon Papers during the legal proceedings had now, after the decision, stopped printing the documents. “Just reporting on the papers as opposed to publishing the papers was a big difference,” Gravel says. “What needed to be done was to publish the papers in their entirety, and that’s what I sought to bring about.”

After fruitless attempts to attract a publisher, Gravel heard from Beacon Press in Boston, which had received an anonymous donation to pay for the cost of publishing the Pentagon Papers. Gravel gave Beacon the documents, and Beacon came out with a four-volume set in late1971. The called it The Pentagon Papers / Gravel Edition.

In his introduction, Gravel wrote, “No one who reads this study can fail to conclude that, had the true facts been made known earlier, the war would long ago have ended, and the needless deaths of hundreds of thousands of Americans and Vietnamese would have been averted. This is the great lesson of the Pentagon Papers. No greater argument against unchecked secrecy in government can be found in the annals of American history.”