Columbia President Lee C. Bollinger Looks Back on Two Remarkable Decades

You have led Columbia for more than twenty years, a tenure second only to Nicholas Murray Butler’s. It’s a demanding job, so we have to ask: Why so long?

For me, it’s been the perfect job. When I took this position in 2002, I was convinced that of all the university presidencies in the United States, Columbia’s was by far the most interesting, in part because the institution had the greatest potential yet to be realized. We all know that Columbia had long been among the greatest universities in the world yet had suffered some very difficult decades, especially in the late 1960s and the ’70s, which happens to be when I was a law student here. By the time I returned as president, Columbia was on the rebound but faced new challenges, a lack of space chief among them. Universities across the nation were undergoing enormous expansion — physically and in terms of their student population and faculty — and Columbia had limited options to grow in the dense urban environment of New York City. So the moment seemed decisive. Columbia could either find a way to make some major moves or risk falling out of the top tier of universities.

At the same time, I saw enormous potential to cultivate new relationships with alumni, with whom our connections had faded, and to strengthen our fundraising operations. And just walking around here, you sensed there was so much that could happen, given the intensely intellectual climate. It was exciting to take all of this on. And it’s taken two decades to do the work I felt needed to be done.

How would you say Columbia has changed since you became president in 2002?

A good measure, in my view, of successful leadership is whether you leave the institution with a meaningful future. Columbia now has a brilliant future ahead of it. There is room to grow. The new Manhattanville campus, for one, is not even one-third built. We have a more engaged alumni community and a much stronger base for fundraising. The institution is in better organizational shape as well. People will still complain about Columbia being inefficient, but I would argue that the administration is better organized and more responsive than it’s ever been. Academically, I’d say that Columbia now maintains a culture of creativity and excellence such that we expect every department to be among the top in its field. We’ve become a more global institution, with Columbia Global Centers in cities across Europe, Asia, Africa, and South America. And Columbia has taken the lead in transforming how universities conceive of themselves as actors in the world in cooperation with outside partners, pursuing what I’ve called the Fourth Purpose of the university. We’re devoting more of our energies to addressing real-world problems affecting people’s lives, including climate change and the COVID-19 pandemic.

You’ve certainly pursued a bold agenda. To use a baseball analogy, you’ve been swinging for the fences pretty much since day one.

There’s no question that I like living in the realm of big ideas. I enjoy thinking long-term and then working toward an ambitious vision, day in and day out. I mean, what better job could you have than to help chart the future of one of the world’s greatest institutions of research and teaching, with the goal of maximizing our contributions to human welfare? And when you approach your work that way and get other people onboard, then all sorts of new and interesting possibilities open up.

Building the Manhattanville campus, which I think everyone knows I’m very proud of, was a big idea. In the beginning, people told me it was a crazy, ridiculous proposition. They said, “There’s no way we’ll be able to develop a whole new campus in West Harlem.” But I thought it was imperative that Columbia attain the long-term capacity for growth. A great university shouldn’t be in the position of telling its faculty and students that they can’t undertake new intellectual pursuits because of a lack of space. And so we set our minds to developing Manhattanville, and after years of working closely with local residents, clergy, business leaders, activists, and city leaders, we made it happen.

My administration has since helped to establish major interdisciplinary research programs in neuroscience, data science, climate science, and precision medicine. Columbia faculty and students are making extraordinary contributions in these areas, and the programs are popular on campus. Inevitably, people will debate what resources ought to be devoted to new endeavors like these relative to existing programs, but nobody questions their importance.

You’ve also overseen the revitalization of Columbia’s alumni-relations and fundraising efforts. What is the most important thing you’ve learned about the role that alumni and donors play and how to engage them?

I’ve seen again and again that having a vision and sense of mission is critical to fundraising success. People typically ask deans and university presidents, “How much time do you spend courting donations?” But I’ve never thought about it that way. Better to ask me, “How much time do you spend articulating what the University might achieve with additional resources?” Because that’s what fundraising is. It’s not about going into somebody’s office and charming them. It’s about engaging them in this incredibly exciting institution and inviting them to participate in making it even better. And that’s a pleasure, truly a joy.

Also, by talking to alumni you come up with ideas for enriching the experiences of current students. For example, early on I noticed that alumni love to share memories of meeting prominent figures who visited campus when they were at Columbia. At first, I didn’t think much of it. But then I realized, “My goodness, of course, what an incredible thing for a young person to be in the same room with the president of India or the Dalai Lama and to be asking them questions!” That realization helped inspire our creation of the World Leaders Forum, which has brought hundreds of heads of state and other dignitaries to campus since 2003.

You’ve staked out a clear place for Columbia as a global university. But we’ve recently witnessed a reaction against globalism in the world — from Brexit and other isolationist movements to rising geopolitical tensions and migrant crises. Do you still think the future is global?

Yes, I do. The world is incredibly integrated now, and despite the existence of countervailing forces, it will remain so. It’s important to understand, though, that creating an identity for Columbia as a global institution was never about endorsing globalization per se. The motivation has been to support scholarship and teaching that helps people to make sense of this complex new world we’re living in and to think on a more global scale. The momentous changes that we’ve witnessed in recent decades — the integration of the world’s economies, the spread of information technology, the movements of people around the globe — are relevant to scholars in nearly every discipline. In my own field of First Amendment law, for example, it’s no longer enough to be steeped in the history of US free-speech cases. Now, with the Internet, we’re confronted with all sorts of new questions: What happens if a journalist is murdered in another country for a story they publish on an American news site? What moral responsibility do we have to help people prosecuted overseas for things they post online that we read? What should we do if our own government tries to prevent us from accessing information online that it claims is dangerous propaganda from another country? People across academia are grappling with complicated issues like these, and the issues aren’t going away.

Being a First Amendment scholar seemed to prepare you well for leading Columbia, since college campuses have always been hotbeds of debate about freedom of expression.

Certainly, the issue of free speech is central to running a university. That’s another thing that I loved about this job. I could continue to be engaged with my field, teaching and writing books, while those activities directly informed my work as president. Everything worked together. That was important for me.

So how do you respond to critiques, often lodged by right-wing commentators, that US universities have become intolerant of conservative viewpoints?

Well, I have no doubt that there are problems with intolerance across colleges and universities today. We see it in the news with some frequency now, where public figures who’ve been invited to speak on campuses are subsequently disinvited because people object to their ideas. And I’ve heard from students on the conservative side of the political spectrum who say they feel uncomfortable speaking freely because of social pressure. Faculty say it can be difficult to generate full discussion on some topics. These are significant issues, and they concern me. In speeches and in meeting with students, I always emphasize the importance of listening to different viewpoints.

I must add, though, that these problems are being exaggerated by political actors who want to discredit universities in the eyes of the public. And this can obscure the fact that US institutions of higher education, despite the internal challenges we face, are still among the world’s staunchest defenders of the open exchange of ideas. For example, at Columbia, we regularly host provocative speakers of all political stripes, including speakers whose ideas I consider wrong-headed, offensive, and even dangerous. Yet the events proceed smoothly, generating spirited and civilized debate.

It shouldn’t be surprising, moreover, that academic communities, like any other communities, would struggle to decide how permissive to be of speech that is widely perceived as noxious or offensive. It’s human nature to be intolerant of unpopular viewpoints. That’s exactly why we have a First Amendment — to make sure that controversial opinions can be aired. On college and university campuses, young people are taught to overcome that natural tendency to be intolerant; it’s an integral part of the educational experience.

Columbia students often do protest when controversial figures speak here.

And I support their right to do so. Protest is a valid form of counter-speech. The protests rarely, if ever, turn obstructive in a way that could be considered censorship. We have worked hard to make sure that doesn’t happen. Furthermore, in my time as president, Columbia has resisted revoking any speaker’s invitation. And we’ve faced intense pressure to do so, most notably when Iranian president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad was invited by our School of International and Public Affairs to appear here in 2007. I think that disinviting controversial speakers is always a misguided decision.

In any case, the most significant threats to free speech on campuses today are coming from outside academia, not within it. I’m thinking of the coordinated efforts by politicians in some states to roll back academic freedoms, such as by restricting the teaching of critical race theory, and to demonize particular groups of students and faculty, including those from China, by suggesting they’re national-security threats. These efforts are very harmful, very destructive, to higher education and to society in general.

Is there anything that you wish you had done differently as president?

Of course, I have some regrets. Most have to do with feeling that sometimes I wasn’t there enough for people when they needed me. In this position, so many people — faculty, students, administrators — look to you for counsel every day. I don’t think it’s possible to be an empathetic person in this role and not feel like you just didn’t have enough time.

The job must take a lot out of you, physically and emotionally.

This is a really, really hard job. Universities are among the most difficult organizations to lead, in part because of their complex structures, and there are times of enormous challenge and stress. It tests you on every level. But it also engages you on every level, and this ultimately inspired me and enabled me to thrive.

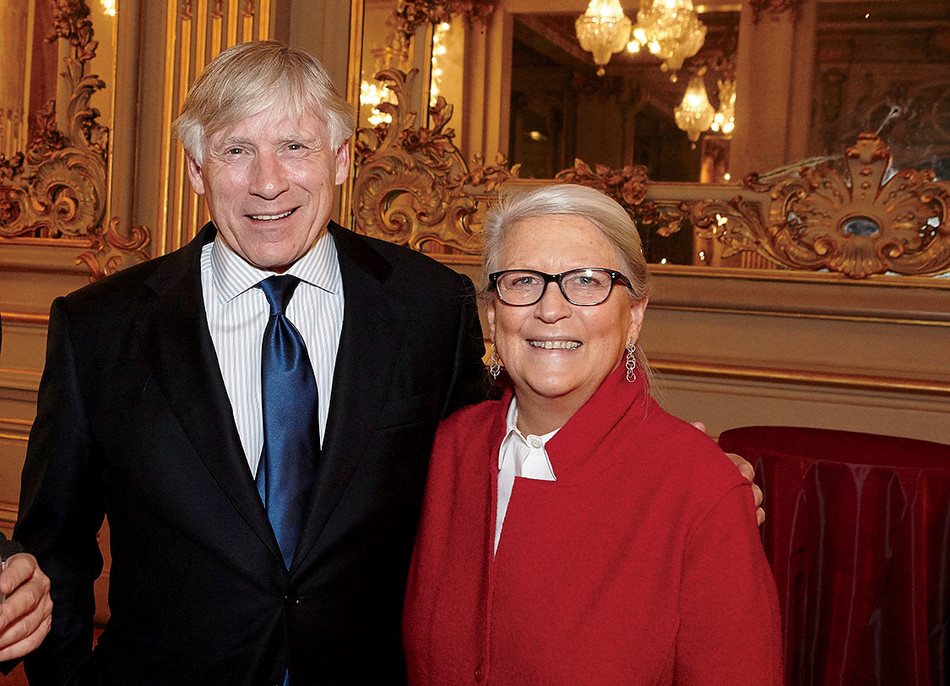

I must add that my wife, Jean Magnano Bollinger, was a true partner to me in this work. And the demands on her time and energy were extraordinary. Despite having her own career as an artist, Jean was very active in the life of the University. She got involved in efforts to advance racial equality, women’s rights, and other causes. And she contributed to the planning of many important initiatives. The idea to build our new arts building next to the Jerome L. Greene Science Center in Manhattanville came out of conversations between me, Jean, Nobel Prize–winning neuroscientist Eric Kandel, arts dean Carol Becker, and others about the connections between modern art and brain science. The creation of the Columbia Global Centers can be traced back to a meeting that Jean and I had with the king and queen of Jordan, who asked if Columbia faculty would be interested in participating in their efforts to secularize the country’s public-education system. Jean has had a hand in many transformative ideas.

You’re a fervent proponent of affirmative action, and you’ve overseen initiatives aimed at diversifying Columbia’s faculty and student body. But the US Supreme Court now seems poised to strike down the 2003 ruling in Grutter v. Bollinger, a case that affirmed that US universities can consider race in admissions without violating the Constitution, and which bears your name from your time as president of the University of Michigan. If the court overturns that precedent, what will be the ramifications for higher education?

The ramifications will be dire. It will be an absolute tragedy and a deep shame. Affirmative action in higher education is one of the most powerful tools we have in the United States for addressing centuries of invidious racial discrimination. The consequences of that discrimination persist today, not least of all in children’s unequal access to high-quality K–12 instruction. College admissions policies that account for an applicant’s race or ethnicity help level the playing field for Black, Latino, and Native American applicants. When you ban such policies — as California, Michigan, and several other states have done in recent years — the proportion of the student population that’s composed of people of color can drop dramatically, sometimes by 50 percent or more. So if this Supreme Court rules that college admissions need to be completely colorblind, as many legal scholars anticipate based on the justices’ questions in a pair of affirmative-action cases they heard last fall, the results will be horribly unjust.

The way you talk about this is interesting. Other university presidents, when discussing affirmative action, tend to emphasize how campus diversity enriches the educational experience of all students. They rarely talk about affirmative action as a way of righting historical wrongs. Why is that?

This is a sad example of how a US Supreme Court ruling, in this case its 1978 decision upholding affirmative action in Regents of the University of California v. Bakke, has shaped our public discourse for the worse. Justice Lewis F. Powell Jr., in his controlling opinion in the case, wrote that universities and colleges could consider the race of applicants, but only for the purpose of creating a diverse learning environment. Since then, every university president, provost, and dean has been told by their general counsel, “If you say we’re doing this to combat racial injustice, our admissions policies could be declared unconstitutional.” I’ve been very open in saying that Powell’s opinion in Bakke was overly restrictive. For decades, the opinion has limited discussion about the real reasons and needs for affirmative action in the United States, leading proponents to make arguments that sound unconvincing and out of touch with the realities of race in America. When I discuss this topic, I’m always careful to specify that I’m speaking as a constitutional-law scholar and as a litigant in a past affirmative-action case, not as Columbia’s president.

Putting your president’s cap back on, what can you tell us about the tools Columbia will have at its disposal for continuing to promote diversity if the court overturns Grutter v. Bollinger?

Columbia is committed to diversity of all sorts, of course, and will remain so. Our student body is very socioeconomically diverse — as well as racially and ethnically diverse — for an Ivy, in part because we’ve made financial aid a key fundraising priority. But if the US Supreme Court decides that we cannot consider race in admissions, the makeup of our student body is going to change; there’s no way around it. Some people will say, “Oh, well, if you just admit more students from socioeconomically disadvantaged backgrounds, you’ll succeed in addressing both economic and racial inequalities.” But this isn’t a solution, because there are more whites in every income bracket in the US. I think people imagine that we’ll find creative ways of working around the court’s decision, like using an applicant’s ZIP code as a stand-in for their race. But we won’t. We can’t knowingly violate the US Supreme Court’s decision. We’ll have to abide by it, no matter how painful.

On a happier note, the University recently announced that Nemat “Minouche” Shafik, a prominent economist, will succeed you as president this summer. What are your impressions of her so far?

Well, she seems to embody all of the values we’ve been talking about. I’m referring to her commitment to learning, intellectual progress, diversity, social justice, and the betterment of society. And talk about having a global perspective! She was born in Egypt, educated in the United States, went on to earn a doctorate at Oxford University, and then assumed leadership positions at the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund, and the Bank of England before returning to academia and directing the London School of Economics. I mean, this is quite remarkable. Plus, she’s a wonderful person to talk to and a great listener. I think she possesses all the qualities we could possibly hope for in the next president of Columbia.

President Shafik seems to share your conviction that faculty and students ought to harness their academic knowledge to address real-world problems, both locally and globally.

I do believe strongly that we as academics have a responsibility not just to advance knowledge in our fields but also to leverage our ideas to improve people’s lives. My administration has put new structures in place to support translational projects, whether they involve Columbia engineers improving access to clean water in disadvantaged rural communities in the US or climate scientists helping smallholder farmers across the world anticipate rapidly evolving growing conditions. Our most visible step in this direction was to launch Columbia World Projects, a University-wide initiative that provides financial, administrative, and technical assistance to such ventures. But we’ve explored making additional changes behind the scenes, like updating our tenure-review procedures so that faculty members are rewarded not only for traditional academic achievements like publishing articles in journals but also for translational work that benefits the public. President Shafik, a global economist who’s helped guide macroeconomic policy in Europe and beyond, is clearly adept at turning theoretical knowledge into action. I’m delighted and eager to see where she takes these initiatives in the years ahead.

What’s next for Lee C. Bollinger?

I started out as a law professor, and I’m happy to return to being a law professor. I’ll still be teaching my course, Freedom of Speech and Press, to Columbia undergraduates, as I’ve done for years, and possibly additional courses at Columbia Law School and around the University. I have several books to work on. The legal scholar Geoffrey Stone and I just edited a large volume of essays about the US Supreme Court’s recent decision to overturn Roe v. Wade, which will come out this fall, and we’re currently editing a forthcoming journal edition about the future of free speech. Next, I want to write a history of US Supreme Court rulings on campaign-finance laws.

Also, I have it in mind to write a memoir. There have been such major events in my time as president of Columbia, starting with 9/11 — the exact day of my meeting with the University’s search committee — right up through the pandemic. In between came the Great Recession — which happened as I was serving on the New York Federal Reserve Bank board — and growing calls for racial justice, increased political polarization, and threats to democracy in the US and abroad. I mean, these are the great transformations of an era, at the beginning of a century. There are just so many themes. Thinking about this great university, and my own life, in the context of these issues is one of the most stimulating things I could do. As you finish something, it’s exciting to look back and try to understand all that’s happened.

This article appears in the Spring/Summer 2023 print edition of Columbia Magazine with the title "Reflections on an Era."