What should a 21st-century university campus look like?

In 2003, when President Lee C. Bollinger announced Columbia’s most significant building project in more than a century, he emphasized that the Manhattanville campus would be a new kind of academic space: one that would foster interdisciplinary research to address the complex challenges facing society and also make a real contribution to the local community.

This spring, Columbia officially opens the first new buildings on that campus: the Jerome L. Greene Science Center and the Lenfest Center for the Arts. The University Forum, a new academic conference center, is under construction, and the Columbia Business School should have a home on the site by 2021. The seventeen-acre parcel of land, located in a former industrial area of West Harlem, will eventually accommodate more than a dozen buildings, to be developed over several decades.

President Bollinger, who has often spoken of the role of great academic architecture in inspiring the pursuit of knowledge and creativity, engaged the world-renowned architectural practice Renzo Piano Building Workshop to design several of the facilities in Manhattanville and create a campus master plan. In the following essay, architect Renzo Piano ’14HON explains the evolution of the campus’s design and how it reflects a bold vision for the University’s future.

If you are lucky as an architect, you may get an opportunity at some point in your career to design a building that reflects a shift in society. You need to be in the right place at the right time. When I was very young, more than forty years ago, I had such an opportunity when I was chosen to design the Centre Georges Pompidou, the home of France’s national museum of modern art in Paris. That structure, with its glass façades and exposed mechanics, celebrates a change that was then occurring in the European art world, as museums were becoming less intimidating and more welcoming to the general public. I feel that my team’s work for Columbia is similarly exciting, since the final product will likely be seen as proposing answers to two profound questions: What should a twenty-first-century university campus look like? And how should urban universities, in particular, relate physically to their host cities?

Creating a campus from scratch is a complex task, especially in a dense metropolis. When Lee Bollinger invited me to work on this project, alongside Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, in 2003, there was debate about whether Columbia should build a traditional campus. One of the other options was to scatter the new buildings throughout the city. Many other urban universities were expanding in this way. But Lee and other University leaders ultimately decided that this wouldn’t suffice. They said that it was important that the Columbia facilities they planned to build all be situated together, so that faculty and students working in fields as disparate as neuroscience, business, and the arts could intermingle and learn from each other. This is, after all, one of the essential functions of a campus: it creates a shared space where scholars from different disciplines can come together and cultivate diverse approaches to life.

Columbia, of course, already sits on a fantastic campus. Designed by McKim, Mead, and White in the late nineteenth century, the Morningside Heights campus is a small acropolis, with classical buildings, green lawns, and contemplative quads that set it apart from the city grid. This gesture was intended to enclose and protect. Indeed, protection is built into the history of campus architecture. It is an understandable and, at times, even a desirable thing. The intent is to insulate students from the quotidian freneticism of the outside world.

But this strategy of productive remove also creates a space that is fundamentally guarded — the Morningside campus fosters a sense of community, but not an entirely inclusionary one. The gates of 116th Street, in addition to projecting an aura of dignity, also confer a sense of asylum and fortification. And the architecture is a bit intimidating. The heavy stone walls, marble columns, and historical design elements say to the outside world: We are a cultivated people; trust us. In the past, this was a typical way for universities to convey their authority. When the Morningside campus was built, higher education was still largely for elites. Today, it is more accessible, and Columbia is deeply engaged with its local community. So my colleagues and I, in designing Columbia’s new Manhattanville campus, have a different story to tell.

How do you create a campus that projects a sense of dignity and trustworthiness without being guarded? We’ve attempted to do this in Manhattanville by designing a campus master plan that calls for a radical degree of openness, transparency, and accessibility. Whereas the Morningside campus evokes history, the Manhattanville campus is all about the contemporary. Whereas Morningside is heavy and monumental, Manhattanville is light, airy, and luminous.

No gates or walls will encircle this new campus. In fact, several streets that intersect the land on which the campus is now being built will remain open to traffic. Beautifully landscaped pedestrian paths will extend out into the surrounding neighborhoods, beckoning local residents into the academic sphere. When they arrive, they will find that the first floors of the new buildings are open to the public and offer a variety of community programs. For example, in the Jerome L. Greene Science Center, which is home to the Zuckerman Mind Brain Behavior Institute, there is an Education Lab where schoolchildren can learn about brain science, as well as a Wellness Center where people can get free health services. Next door, in the Lenfest Center for the Arts, members of the public will be able to attend film screenings, theater and dance performances, and art exhibitions.

The activity taking place at street level will be the heart of the new campus. This is where the University and the city will meet. There will be no clear boundary between the two. This is by design. Columbia University’s academic programs are enmeshed within New York City both serving it and drawing inspiration from it. Our new architecture reflects this: rather than pulling Columbia back from the city, it pushes the University forward so that it can be a citizen, too. The pedestrian traffic flowing through these buildings will also give them a certain lightness. A good building, I like to say, can fly. Sometimes, a well-placed beam or column creates a sense of upward motion that lifts your structure off the ground. Of course, Columbia’s new buildings touch the ground, but they are public on the street level; they’re permeable, porous, and accessible. There is no frontier between the buildings, the city, and the street. If buildings are to be loved and embraced, they cannot be selfish.

Manhattanville has proved to be the perfect location. It is only a ten-minute walk from Morningside Heights, which means that events taking place at the new conference center that is slated to open in 2018 will be easily accessible from the main campus. The stretch of land we chose was suitable also because most of it was underdeveloped, with lots of vacant warehouses and garages. On top of that, the surrounding neighborhood of West Harlem is an incredibly diverse one, known for its vibrant street life, street art, and street music. This will give the campus a terrific energy.

This spring will come the moment of truth. When a new building is finished, I like to stand nonchalantly behind some beam or pole and watch people walking in. Sometimes they look beaten or disconcerted. Other times they smile. If they look happy, I know I have done my job. It means that I’ve given back to the city that which it gave me: a good space.

The Jerome L. Greene Science Center

Clean Machine

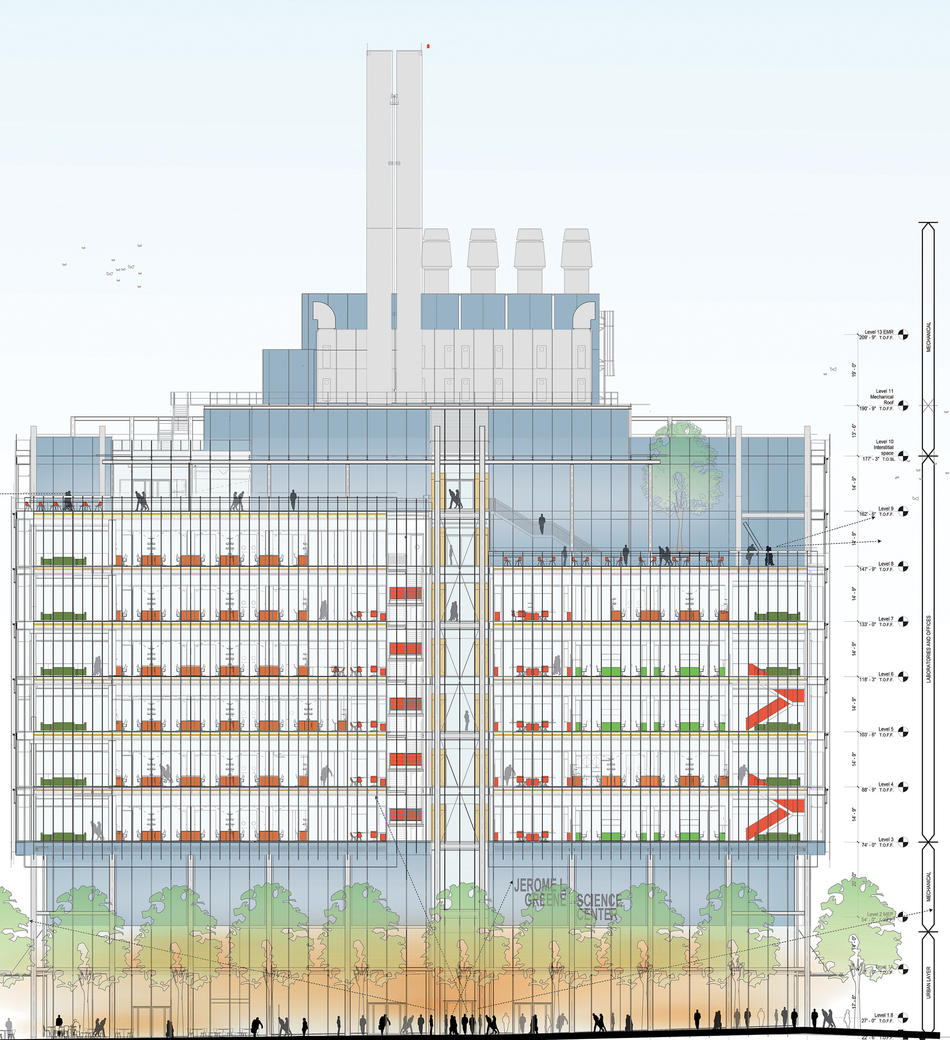

Like all new buildings on the campus, the Jerome L. Greene Science Center is intended to be a model of environmental sustainability. Architects at Renzo Piano Building Workshop, working with local architectural firms Davis Brody Bond and Body Lawson Associates, designed the building with a highly reflective “cool roof” to mitigate the summer heat. The space is also equipped with solar sensors that raise and lower window shades to help regulate temperature and a double-skin glass façade that acts as an insulator.

A Palace of Light

The 450,000-square-foot Jerome L. Greene Science Center is the home of Columbia's Mortimer B. Zuckerman Mind Brain Behavior Institute. Here, hundreds of scientists from a variety of disciplines will pursue collaborative research in neuroscience. The building has an open-floor concept and interactive spaces where researchers can meet and exchange ideas. Renzo Piano says the building's glass façade provides the scientists inspiring views of the city while enabling passersby to observe the researchers working in their laboratories. “It is a palace of light,” says Piano. “Its transparency is meant to underscore that the knowledge being generated inside is for the public and will be shared with them.”

The Lenfest Center for the Arts

The Creative Hub

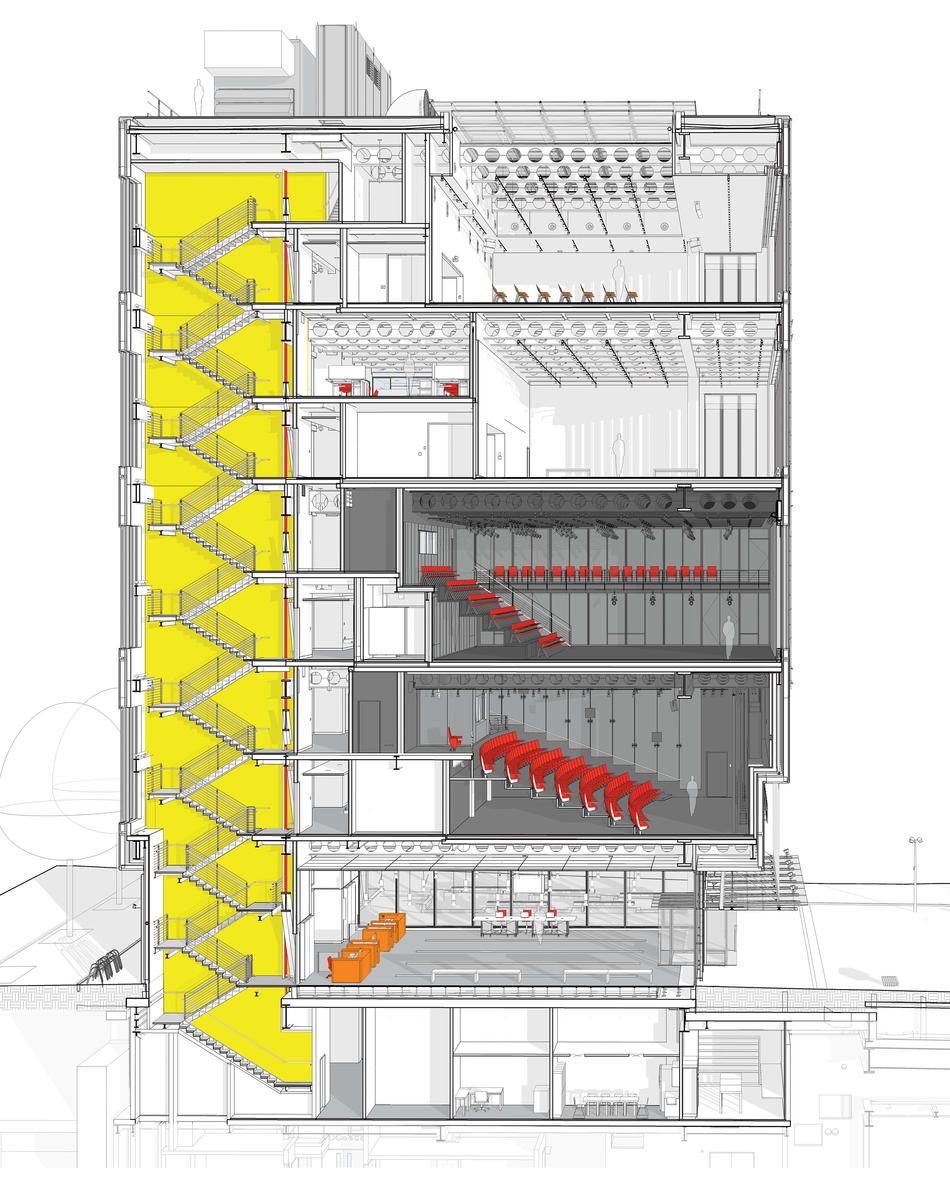

With the opening of the Lenfest Center for the Arts, Columbia’s School of the Arts and the Wallach Art Gallery will have dedicated spaces to showcase the works of students, faculty, and visiting artists. In order to achieve column-free spaces in the performance areas, lead architect Renzo Piano distributed the building’s weight onto vertical beams positioned around the perimeter. Says arts-school dean Carol Becker: “The center is going to allow us to reach new audiences and to build deeper relationships with local communities.”

The Future

Open To All

Key to the new campus's feeling of openness and accessibility will be its green space, public plazas, and wide sidewalks lined with trees. The goal is to make the campus inviting to neighbors as well as to provide a scenic path to the new West Harlem Piers Park, which Columbia helps to maintain along the Hudson River waterfront.

A New Kind of Campus

The Manhattanville campus will be developed gradually over several decades. By 2021, there will be at least three new buildings on the site in addition to the Jerome L. Greene Science Center and the Lenfest Center for the Arts: the University Forum (above), a conference center designed by Renzo Piano Building Workshop with Dattner Architects and Caples Jefferson Architects; and two Columbia Business School facilities (left), the Ronald O. Perelman Center for Business Innovation and the Henry R. Kravis Building (detail, right), both designed by the architectural firm Diller Scofidio + Renfro, together with FXFOWLE Architects and Aarris Atepa Architects. Thousands of faculty, students, and administrators will study and work on the Manhattanville campus, and members of the community will be able to enjoy the wellness and learning centers, cafés, and art exhibits open to the general public. “You will have science, art, and community — the essence of a campus,” says Renzo Piano. “Yet it will be a new kind of campus in that it will embrace the complex urban condition.”