When one thinks about what makes Jack Eisenberg’s pictures click, it is hard to avoid Henri Cartier-Bresson’s description of his own photography from his 1952 book, The Decisive Moment. Every one of Eisenberg’s images embodies what the French artist saw as “the simultaneous recognition, in a fraction of a second, of the significance of an event as well as the precise organization of forms which gives that event its proper expression.”

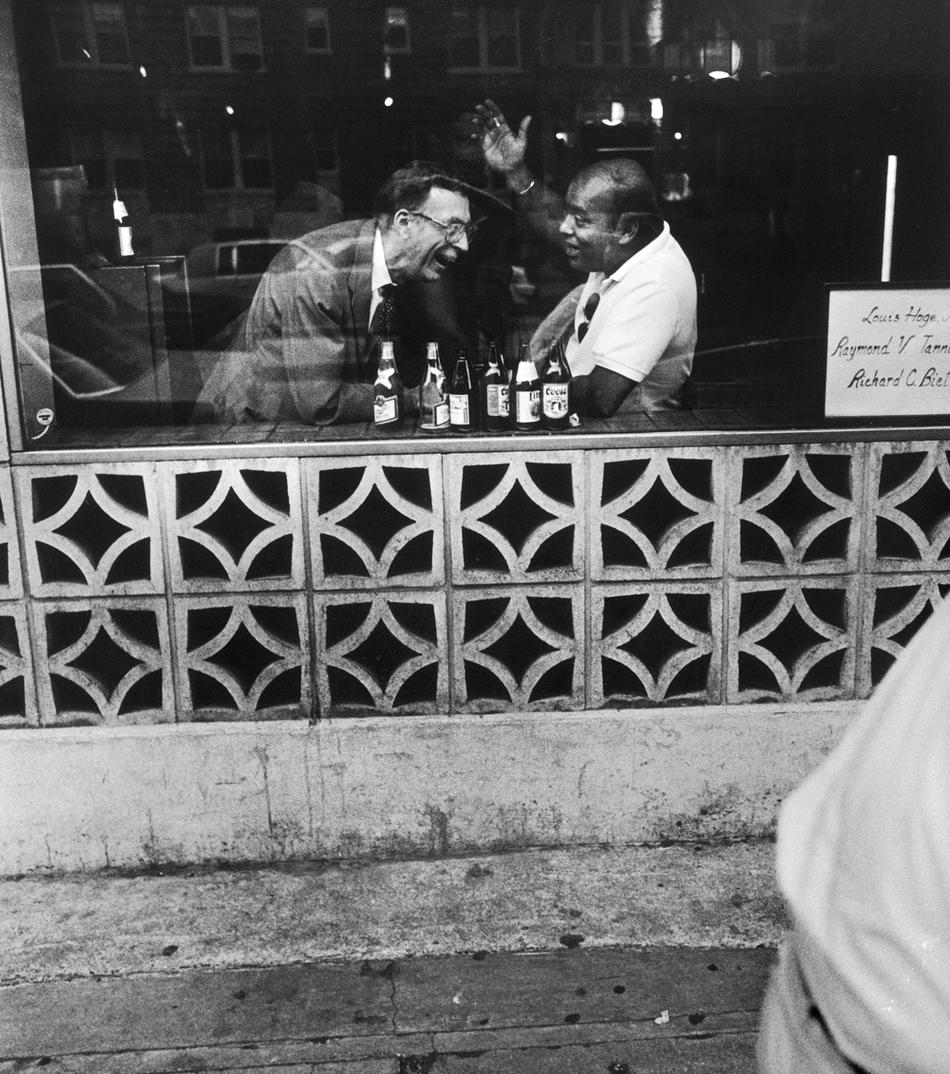

Look at this photograph of two friends in the window of a Baltimore bar. Eisenberg released the shutter at the peak of one man’s laughter and when the other’s gesture is at its most expressive.The composition — “the organization of forms” — is typical of Eisenberg: Our eye goes first to the strong, primary subject, and only on second glance notices the supporting players, those little extras that comment on the scene. In this case, the blurry figure to the right and the reflections in the glass tell us that this is a busy street — and that our two friends are oblivious to it. Capturing this is partly technical skill and partly artistry. But what elevates Eisenberg’s body of work to an even higher level is the compassion, affection, and even love he brings to his subjects. Can anyone look at these two men (and their empty bottles) and not smile? Can anyone look at the two pictures on page 21 and not understand what death does to those it leaves behind?

Eisenberg was born in Baltimore in 1940 and came to Columbia College in 1958, an era of brightly shining faculty stars. He studied with Meyer Schapiro (“The most brilliant man I knew at Columbia”), Mark Van Doren (“He could say more in a sentence than Trilling could say in four months”), and Lionel Trilling (“Still the greatest influence on me intellectually”). After graduating, Eisenberg taught high school history, took a job as a social worker in Baltimore, and became a trooper in the civil rights, antipoverty, and anti–Vietnam War movements. He started taking pictures seriously about 1966 while working for the Baltimore Department of Public Welfare and the following year during a trip to Israel. He had flown there in May 1967 to fight (“if necessary”) in what turned into the Six Day War,“but by the time I got there, it was over.”

While Eisenberg follows a tradition of street photography exemplified by Cartier-Bresson and André Kertész, his work has an emotion and an intimacy that the images of the masters sometimes lack. He works exclusively in 35mm and generally shoots with a 35mm or 20mm wide-angle lens. These lenses give his photographs considerable depth of field and of course simply include a lot of what surrounds the subject, which is apparently how Eisenberg sees. These short lenses also compel him to move close to his subjects, and this requires courage: It is difficult for a sensitive man to stick his camera in the face of rioters and soldiers in Ramallah. It is even harder for him to raise his little Leica to photograph an individual’s grief or a couple’s private tenderness.Yet there is no sense of intrusiveness to these pictures because we feel that Eisenberg was supposed to be there. With some photos that was literally true; he came to know many of the people he photographed, and they probably came not to notice his camera. Photographing them was his way of looking at them and communicating with them. (Having spent a few days with Eisenberg in Baltimore this year, I saw that he and his Leica M4 were always attached to each other. I also appreciated how quickly he spots a potential photo and then captures it on Tri-X film.)

Eisenberg has taken thousands of photographs and the best are moving, hilarious, or upsetting — and could have been taken only by him. Magnum photographers Cornell Capa and Leonard Freed have praised his work; the Israeli photojournalist Micha Bar-Am, also of the Magnum agency, called it “damn good.”Yet Eisenberg has had just a few exhibitions and a couple of features in the Baltimore Sun and in Jewish publications, so not many people outside Maryland and the photography world have seen his pictures before.

“Although I didn’t become an all-out photographer until 1969,” Eisenberg says,“my Columbia years played a tremendous role in orienting me toward the kind of photography I do.This period coincided with my exposure to the movement that Cornell Capa later gathered in the Concerned Photographer exhibition and books; I remember excitedly discussing my discovery of Roman Vishniac with Meyer Schapiro.Another thing was learning to interrelate different disciplines: psychology, history, and photography, for example.

“But most of all, I think of Justus Buchler’s CC-B, the second half of the Core’s Contemporary Civilization course. It’s a shame CC-B is no longer required, because it made us into people who were aware of our own times.”

Nimrod, 1988

“When you see this kind of damage in Israel, it’s 95 percent certain that the injury is war-related. The photo, with the advertisement for Nimrod sandals, was taken outside Jerusalem’s central bus station.”

Lest We Forget, 1988

“I was photographing the Memorial Day Parade in Baltimore when I saw the vet with the brace: He was so alienated from the others in the parade. It wasn’t hard to recognize that he’d been badly damaged by ’Nam not only physically but psychologically as well.”

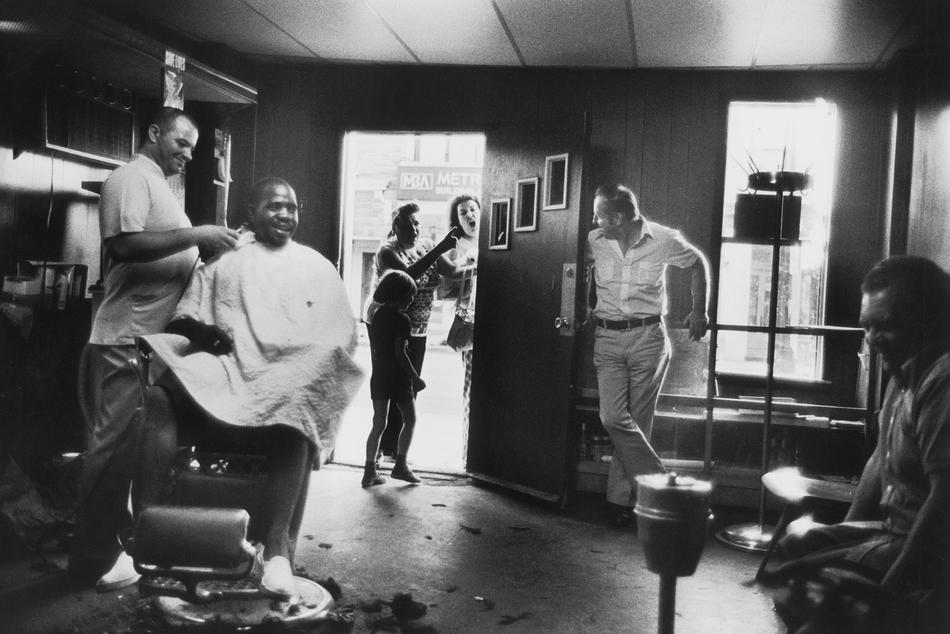

Jim’s Barbershop, 1975

“Waverly is a working-class Baltimore neighborhood bordering Charles Village on the east. Jim Remsberg was the first barber in the area to integrate his shop. In addition to having a good time there, I enjoyed recording the integration process in the shop deliberately but unobtrusively. In this picture, Ed, who had been trying to elude his separated wife, took refuge inside the shop — but has just been cornered. It was a really comical moment. In 1990 Jim was killed in a holdup.”

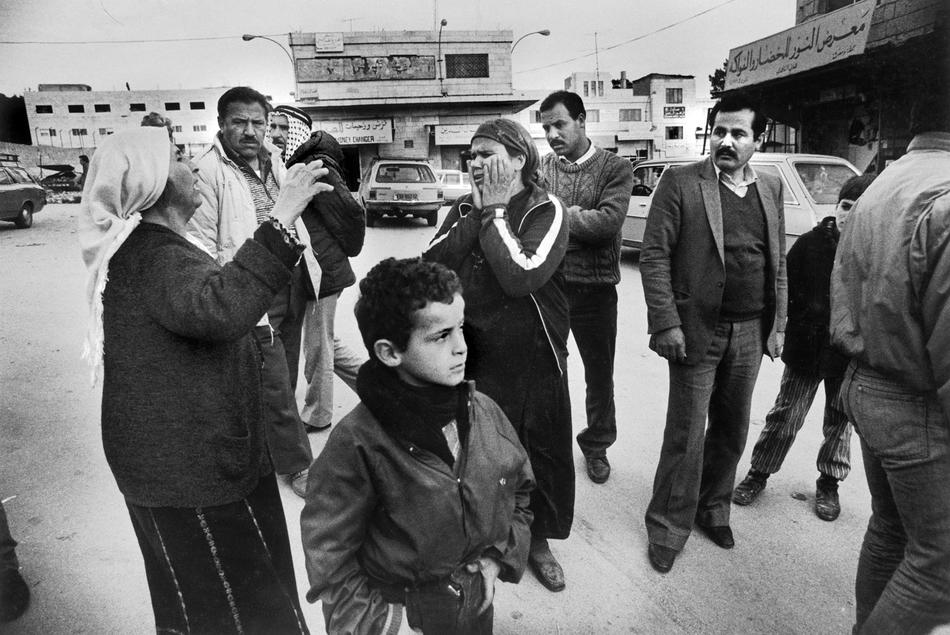

Ramallah, January 1988

“I was in Ramallah during the rioting that marked the beginning of the first intifada when I came across these two women. The mother, on the left, was telling people that her son had been arrested by the Israeli Army. But the boy in front is what struck me.”

Urban Renewal, 1975

“The city was tearing down huge globs of innercity Baltimore to make way for new housing. I was doing a story about my uncle and aunt, who were almost the last Jews remaining in this area.The picture was taken less than a block from their combination store and home and within a block of where my father’s large immigrant family grew up. Within a year of the time this photo was taken my uncle and aunt had to relocate to the suburbs, and the whole area is now a matter of historical record.”

Leap of Faith, 2000

“I was coming from the funeral of a high school teacher, who had been murdered in the West Bank with several of her students the day before by terrorists. These children were playing near the bus stop in Sanhedria, Jerusalem, where I awaited the bus home.”

New Orleans Dock, 1966

“I took this picture while on vacation from my social work job at the Baltimore Department of Public Welfare.The men are unloading rubber from the Philippines. Scenes like this were already disappearing after the introduction of container shipping, and the picture takes on added meaning given the recent Katrina tragedy. It’s one of my first good pictures, and I still consider it one of my very best.”

Political Debate, 1981

“We called this block The Strip, and for many years it was the center of both commerce and the rich street life of the 1970s and ’80s. In the words of a reporter, it’s “where the ’60s came to die.” Fortunately, they were still alive enough here for me to have made this picture.The kid is part of a Trotskyite group that demonstrated each week outside the local bank, which was especially busy for obvious reasons on Friday afternoons. The woman was a very patriotic Republican conservative in a generally liberal neighborhood and was a lot of fun. Scenes like this rarely take place these days. People don’t talk to each other as readily.”

The Explanation, circa 1980

“I became friends with Betty and her family, whom I met and photographed while walking in downtown Baltimore. I dropped in on their St. Paul Street apartment one nice, warm day just to say hello and was greeted by the news that her husband had been drowned the day before in a fishing accident. Here she’s trying to explain this to her two sons, who cannot quite grasp what’s happened. ‘Your daddy’s in heaven,’ she told them.That’s a direct quote.”

Philadelphia Road Cemetery, 1983

“When my uncle died, my father and I had to purchase a plot for him in this old Jewish cemetery in Baltimore. My father is shown passing the graves of his parents, Jacob and Theresa.”