What challenges did you face when you started your career in 1961?

I was twenty-three, and DC was a very segregated city. We didn’t have the public-accommodations bill. We didn’t have the voting-rights bill. Even though the civil-rights movement was kicking into high gear, a lot of restaurants still didn’t serve Blacks. Just getting the job done was a challenge. When I went to do an interview, time was of the essence, but I often couldn’t find a cab to take me across town. When the drivers saw my dark-brown skin they would press down on their accelerators. People were so unaccustomed to seeing Black reporters that they wouldn’t believe I was a journalist. I was once assigned a story about a white woman who had turned one hundred. When I got to her apartment building, the Black doorman looked at me coldly and said, “The maid’s entrance is in the back.”

That must have been incredibly difficult, especially without mentors who had dealt with these barriers before.

My Columbia professor John Hohenberg ’27JRN had tried to prepare me for what it was going to be like. He said, “You have so many handicaps, you’ll probably make it.” The idea that my very person — separate from my abilities — could hamper my success prompted a tiny roar inside me. When I look back on that time, it felt like I was about to dive into a sea of white men, carrying weights they didn’t have — in one hand was race, and in the other was gender. And that is some tough swimming. But if I didn’t make it, it was going to be really hard for the next Black person to be hired.

How did you get the job done, despite the obstacles?

I had to think practically and I had to learn to be courageous when working in the Deep South war zone. A year into my job, when I was covering the integration of Ole Miss, I spent the night in a funeral home because I knew I would be risking my life if I tried to stay in one of Oxford’s white hotels. But I was glad of a clean, safe place to lay my head. Besides, Black funeral directors were the go-to people for information for Black reporters.

You struggled with depression and anxiety. Can you talk about the psychological pressures of being the first and only Black woman in these white spaces?

I think I was just so shocked. Going into white neighborhoods often amounted to an invitation to be abused. I had white colleagues who wouldn’t speak to me when they saw me on the street because they didn’t want to acknowledge me in front of other whites. It was humiliating, and I was angry. But I took a lot of strength from religion and the Black church. Martin Luther King said that hate is too heavy a load to carry. So I tried to take that to heart.

You wrote that when you first started as a reporter, you didn’t want to be boxed in and only cover Black stories. What advice do you have for young Black journalists?

I think that I was a little naive to stereotype myself. I wanted to show that I could do any type of story. But we had Kennedy in the White House, and he was talking about the “new frontier,” and then came the war on poverty. Martin Luther King was a big part of the news cycle. Welfare was becoming an important topic. Black people were major players in those stories, and I was distancing myself from them. Now, when people say they don’t want to do Black stories, it saddens me, because they are missing some really important things.

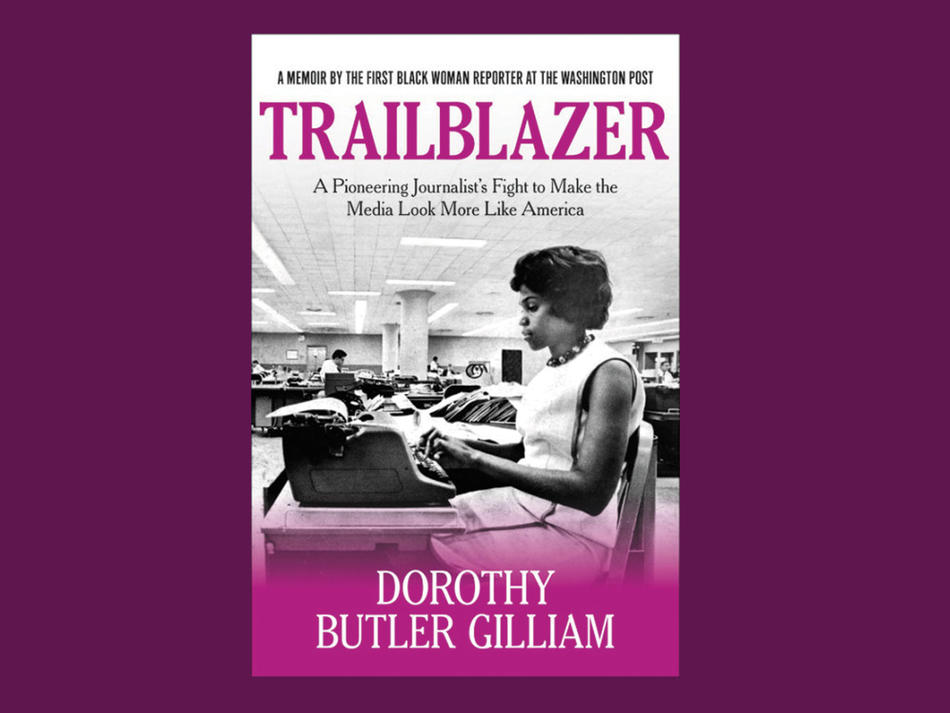

Your book is a testament to the critical role that reporters play in the democratic process. Did you write it to remind everyone of that?

When I decided to write a memoir, I had no idea it would be published in such a significant time. As I was reading the proofs, I kept hearing the term “fake news.” Fellow journalists were being called the enemy of the people. I wanted to talk about the training, ethics, and hard work it takes to tell the truth, to the extent that it can be told.